We recognize them by their signature yellow-black stripes and for being invaluable to our ecosystem. These queen bumblebee facts will only add to that.

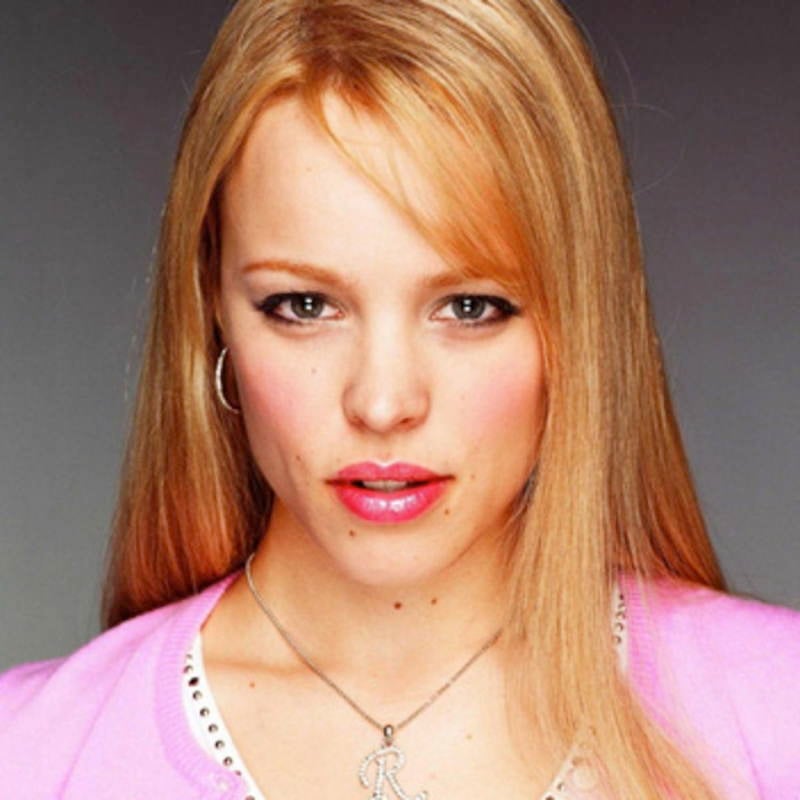

First off, we’re talking about this kind of Queen Bee:

Not this kind:

But when you get right down to it, they’re pretty similar. Both have striking features, they’re known to fight lesser creatures who threaten their social status, and they’re both bad bitches. Nobody ever said life on top was easy.

Being the biggest and slowest bee of them all, work starts early in the spring for the lethargic queen bumblebee, who is quite hungry as she’s been hibernating since the past summer. When the first flowers and bulbs begin to push their way through the soil, the queen ends her winter-long nap, feeds on these early-bloomers and starts to search for a new nest.

Source: Touch Of Modern

But before we get too deep into colony life, let’s take a moment for some trivia: Darwin originally called these guys “humblebees” because of the humming noise they make when they fly. It wasn’t until World Wars One and Two—when sleek, streamlined planes became mainstream—that the name bumblebee rose to prominence. These cruisers made the insect look bumbling and confused by comparison.

Source: Wikipedia

Anyway, the queen will bumble from place to place until she finds the perfect location for her home, which is usually an abandoned rodent burrow or a protected spot under a garden shed. Even a pile of old, dead leaves will do. Unlike honey bees, bumblebees build a new nest annually, and they generally build their nests in the ground.

Source: Medium

After the queen has found her prime piece of real estate, she collects enough nectar and pollen from early bulbs and flowers to produce a ball of pollen and wax. The queen, having shacked up with her mate the previous summer, lays about six eggs in it at a time. The eggs hatch, and the resulting grubs attempt to fight through their pollen protectors.

This process can take up to twenty-one days, because the queen will keep adding pollen and wax to keep the grubs inside until they have developed enough. At that time, the queen spins a fine silk cocoon for each grub. When they finally emerge a few days later, they are fully developed worker bees, and ready to help build the nest. A worker bee is always female, and the queen’s eggs must be fertilized for a female bee to hatch. Male bees, or drones, are the product of unfertilized eggs, but more on them later.

Source: University Of Illinois

From this point on the queen becomes a prisoner in her own nest, and spends almost all of her time laying eggs. The queen is the only female bee in a colony who will reproduce. While she is in charge, she can emit hormones which suppress the development of ovaries in worker bees.

Source: Today I Found Out

Occasionally an especially feisty worker will resist these hormones and try to usurp the queen by laying her own eggs. To fend off this wannabe Mary Queen of Scots, the queen will eat the worker’s eggs, use pheromone signals to assert her dominance, or fight with her stinger. This brutal reproductive competition is the reason bumblebees are classified as “primitively social” creatures; the queen will do anything to stay on top.

Source: Reddit

At this point, it’s late Spring and the worker bees are ready to take over the pollen-nectar collection and the construction of the nest. Bumblebee colonies are usually made up of about 50 individuals, but under some circumstances can include up to 400 insects. For this reason, a completed nest is usually about the size of half of a grapefruit.

Source: Arkive

Bumblebee nests are far less regular than honeybee hives and will have several entrances. The nest is usually insulated with soft, fibrous plant material or animal fur, and are built with wax, which the worker bees secrete from their abdomens. When they mix that wax with pollen, it becomes a sturdy yet pliable building material, which dries hard. They build oval-shaped cells to store nectar, pollen, or eggs.

Source: Tiki Rau

There are over 200 species of bumblebees. Most but not all are found in North America. Some species are more aggressive than others, but most are quite docile unless they feel their lives are in direct danger. Female bumblebees (queens and workers) are the only ones with stingers. Males are stinger-less and basically useless. Classic.

The drones and new queens generally hatch mid Summer. The drones leave the nest as soon as they transform from larvae into adult bees, and after this they lead short, solitary lives. Their only real purpose is to mate with the young queens and ensure another generation of female bumblebees.

For the rest of the Summer and into the Fall the worker bees and the queen bee will keep living and working in the mother colony. But like all empires, this bumblebee colony will perish, too. When the first frost comes, the old queen, most workers, and all of the drones die. The nest will become abandoned, and only the newly mated queen bumble bees will survive the winter and start their own nests again in the Spring.