In 1862, Newton Knight deserted the Confederate Army and formed his own company of both free and formerly enslaved men and women to found the Free State of Jones and fight for the Union.

YouTubeMatthew McConaughey as Newton Knight in the 2016 film Free State of Jones

In 2016, actor Matthew McConaughey starred as a pro-Union Mississippi man named Newton Knight who stood up to the Confederacy. Though some in the South protested Knight’s depiction as a hero, the Free State of Jones true story actually hews closely to the Hollywood version.

Just like in the movie, Knight rebelled against the Confederacy during the Civil War. He organized deserters, scuffled with Confederates, and declared Jones County, Mississippi, the “Free State Of Jones.”

Though the movie took some creative liberties, including introducing new figures not mentioned in the historical record, it largely stuck to the facts. Learn what really happened when Newton Knight led Jones County in the battle to secede from the Confederacy.

The Real Story Of The ‘Free State Of Jones’

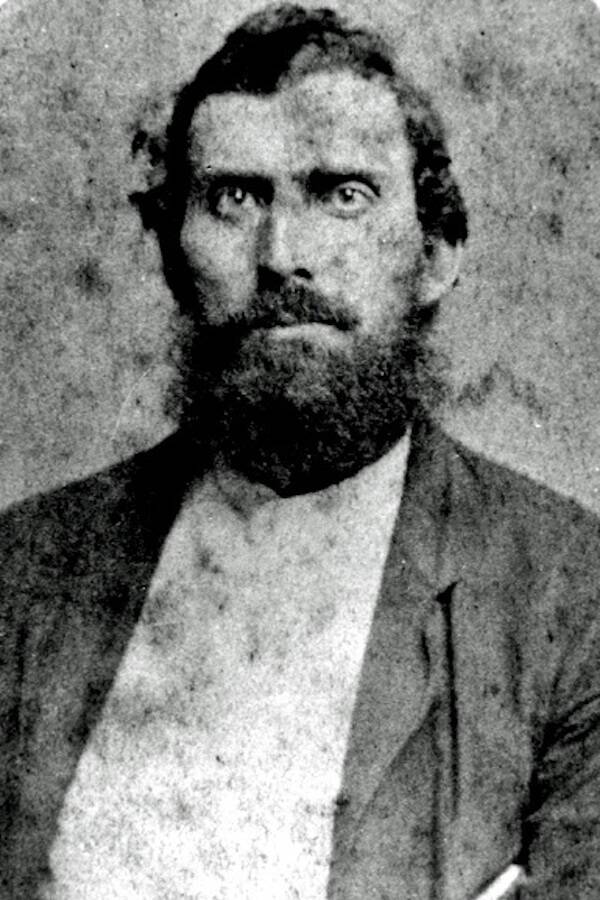

Public DomainIn the true story of the Free State of Jones, Newton Knight became disillusioned with the Confederacy and fought back in Jones County, Mississippi.

The true story of the Free State of Jones started in 1860. Then, as Southern states began seceding from the Union following the election of Abraham Lincoln, people in Jones County, Mississippi, voted to stay.

“Fact is, Jones County never seceded from the Union into the Confederacy,” explained the real-life Newton Knight in 1921. “Her delegate seceded.”

Indeed, Jones County voted for a “cooperationist” delegate over a “secessionist” one by an overwhelming margin. With just 12 percent of its population enslaved, Jones County didn’t have the same urgency to go to war as other parts of the South.

But when that delegate attended the secession convention in Jackson, Mississippi, he lost his nerve. He voted to leave the Union with the rest of the convention.

“He didn’t come back to Jones County for a while,” Knight noted.

Despite any personal reservations on his part, Knight enlisted in the Confederate Army in 1861 at the age of 33. His reasons for doing so are unclear, though historians have speculated that he simply wanted to be a soldier.

In any case, it didn’t take long for Knight to become disillusioned with the conflict. He and some of his fellow soldiers seethed about the “20 Negro Law,” which stated that white men who enslaved more than 20 people did not have to fight.

Knight’s friend, Jasper Collins — played by Christopher Berry in the film — summed up the issue by saying, “This law… makes it a rich man’s war and a poor man’s fight.”

Public DomainKnight’s friend Jasper Collins summed up the Civil War as a “rich man’s war and a poor man’s fight.”

They decided to desert and return to Jones County. But at home, Knight and the others were furious to find their families frequently harassed by Confederate soldiers looking for food or supplies.

When Confederate Major Amos McLemore came to Jones County with a pack of dogs to round up deserters, Knight and the others were ready. Someone — likely Knight himself — shot and killed McLemore on Oct. 5, 1863. Then, the men of Jones County started to organize.

“So we organized this company, and the boys elected me captain,” Knight explained. “They elected Jasper Collins first lieutenant and W.W. Sumrall second lieutenant.”

For two years, the so-called Jones County Scouts stood their ground. They defended their farms, pledged themselves to the Union Army, and even captured the county seat and raised an American flag over the courthouse. Knight and his men dubbed Jones County the “Free State of Jones.”

“There was a lot of skirmishin’ that you couldn’t properly call battles,” Knight said. “But we had 16 sizable fights that I remember, and we lost 11 men. I never kept track of how many wounded.”

He and his men triumphed in their last “skirmish” on Jan. 10, 1865. That April, the Civil War ended — and the true story of the Free State of Jones settled into legend.

The Free State Of Jones True Story Vs. The Hollywood Version

YouTubeMoses Washington (Mahershala Ali) was a fictional character, but depicted real experiences faced by Black people before, during, and after the Civil War.

How does the Free State of Jones true story stand up to the Free State of Jones movie? Though the film largely sticks to the facts, it also takes some creative liberties by adding characters and dramatizing certain sequences.

Take Newton Knight’s young nephew. His death in battle early in the film deepens Knight’s resentment about the war and provides an impetus for Knight to desert. But the nephew (played by Jacob Lofland) did not exist.

Likewise, Knight befriends a man who has escaped slavery named Moses Washington (played by Mahershala Ali) while hiding in the woods. Washington is also a fictional character, though his story seems to seek to capture the experience of many Black Americans before, during, and after the Civil War.

For example — spoilers ahead — Washington goes from an enslaved man to an activist. In the Reconstruction years depicted in the film, he’s castrated and lynched after registering freed Black men to vote. This is seemingly a nod to the real-life stakes faced by Black people in the post-Civil War years.

When it comes to the character of Confederate Colonel Elias Hood (played by Thomas Francis Murphy), the true story of the Free State of Jones is a bit more complicated. Hood never existed. Instead, he’s likely a depiction of Confederate Major Amos McLemore.

In real life, Knight (probably) shot and killed McLemore. In the film, Hood is strangled by Knight during a dramatic funeral-turned-ambush.

Public DomainRachel Knight was real enslaved woman who worked as a spy for Newton Knight’s company.

Free State of Jones does accurately portray Newton Knight’s romantic entanglements, however. He married a white woman named Serena (played by Keri Russell) but entered a common-law marriage with a formerly enslaved woman named Rachel (played by Gugu Mbatha-Raw).

In the film, Rachel is enslaved by a local plantation owner; in real life, she was enslaved by Knight’s grandfather. Furthermore, the movie depicts Knight as having one child with Serena and one with Rachel. In reality, he had nine children with Serena and five with Rachel — and then, after Rachel died, he had several more children with one of her daughters from a previous marriage.

Likewise, Newton Knight’s great-grandson Davis Knight did indeed stand trial for marrying a white woman in 1948, just as in the film. He was charged with violating the state’s anti-miscegenation laws and served five years in prison before the Mississippi Supreme Court overturned his conviction.

The Free State of Jones true story may differ from the film for reasons like these. But the movie also offered a striking look at the hopes, disappointments, and devastations of the post-Civil War years.

Reconstruction And Newton Knight’s Legacy

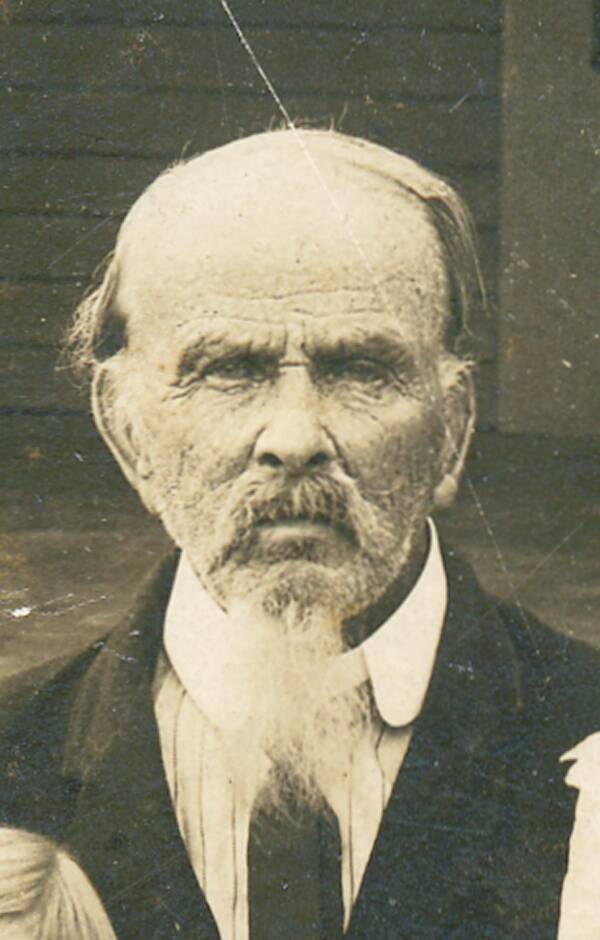

Public DomainNewton Knight and one of his sons with Rachel Knight, a woman who was formerly enslaved by his grandfather.

The third part of the Free State of Jones movie follows Newton Knight into Reconstruction. There, it accurately portrays Knight’s advocacy for newly freed Black Americans.

“I think we need to celebrate alliances,” said Gary Ross, the film’s writer and director. “And it is demonstrably true that Newt was allied with African-Americans all through Reconstruction after a lot of white people in the South had bailed.”

In the film, Knight is depicted leading Black men into town to exercise their right to vote in 1875. And in real life, Knight served in a unit that sought to protect Black Americans’ voting rights.

But though the film portrayed Knight as a hero, the true story of the Free State of Jones’ legacy is more complex.

“A lot of older people see Newt as a traitor and a reprobate, and they don’t understand why anyone would want to make a movie about him,” explained Jones County Junior College history professor — and Knight family descendent — Wyatt Moulds.

“If you point out that Newt distributed food to starving people, and was known as the Robin Hood of the Piney Woods, they’ll tell you he married a Black, like that trumps everything. And they won’t use the word ‘Black.'”

Indeed, many in Jones County felt embarrassed about Newton Knight. After the Civil War ended, and Mississippi rejoined the Union, they renamed Jones County to Davis County, after the Confederate president Jefferson Davis.

The New Orleans Times reported in December 1865 that locals “feel scandalized by the reputation of Jones County as a harbor for deserters, bushwhackers and ‘mossy back’ [draft dodgers].”

The name changed back three years later. But Newton Knight spent most of his life as an outcast. He and Rachel lived in the forest and rarely entered the town.

So, is Free State of Jones a true story? Though the movie takes liberties with its plot, it offers a fairly accurate retelling of Newton Knight and the Free State of Jones. Significantly, it also tackles the messy post-Civil War years and the failed promises of Reconstruction.

After reading about the Free State of Jones true story, looking through these compelling photos from Reconstruction. Or, peruse these colorized photos of the Civil War.