In the early 1900s, Alice Guy-Blaché directed one of the first narrative films and founded her own studio before the glory days of Hollywood. But then, she nearly disappeared from history.

Public DomainAlice Guy Blache, pictured in 1913.

In 1895 Paris, 21-year-old Alice Guy sat beside her boss, Leon Gaumont, at an small, exclusive gathering. Auguste and Louis Lumiére were demonstrating their new invention: the Cinématographe, one of the first film projectors.

The group of 10 were astonished as they watched men and women onscreen leaving the Lumière factory in a carriage. But Guy had a different reaction: “I thought I could do better,” she later wrote in her memoirs.

And so she did. The woman later known as Alice Guy Blaché would go on to make one of the first narrative films — and found a film studio before Hollywood was established.

Alice Guy-Blaché Amid The Birth Of Cinema

It was 1894 at the height of the Belle Epoque, when Paris was a beacon of art and innovation. Alice Guy applied for a secretarial job at the Comptoir Général de la Photographie. She was disappointed that the owner wasn’t there. As luck would have it, she interviewed with the second-in-command, Léon Gaumont, who hired her as his secretary. He later took over the company as it rose to dominate the fledgling film industry.

At the time, the only way to view moving pictures was through a peephole in a large box. Called a Kinetoscope, the device was cumbersome, limited to one viewer at a time, and could only show a flickering movie 20 seconds long. Gaumont was vying with other inventors and entrepreneurs to circumvent these limitations.

Wikimedia CommonsBefore films were projected, they could only be viewed through kinetoscopes like the ones seen here in 1894 or 1895.

When Gaumont and Alice Guy went to the demonstration of the Cinématographe, it was clear that the Lumiére Brothers had won the race to project a film. As the invention gained popularity, Guy gathered up her courage and approached her boss, “I timidly proposed to Gaumont that I would write one or two short plays and make them for the amusement of my friends,” she wrote.

Guy-Blaché’s Pioneering Narrative Films

At the time, moving pictures primarily documented scenes from everyday life. A train going by. Waves on a beach. Alice Guy could have just pointed the camera at something interesting. Instead, she got a few friends together to make The Cabbage Fairy, with painted sets, a costumed character, and a simple storyline. It is arguably the first fictional film.

Public DomainThe Cabbage Fairy was shown so often that the original 1896 film disintegrated within four years. This is a still from Guy’s remake in 1900.

The Cabbage Fairy was such a success that Guy was named head of production at Gaumont. She went on to make nearly 700 films in the next decade including travelogues, dance films, comedies, westerns, and the earliest book adaptations.

Alice Guy helped develop film language with the first examples of close-ups, reaction shots, camera movement, and cross-cutting. She experimented with hand-tinting and double exposure. And as chief of Gaumont’s artistic department, she mentored several filmmakers, including Louis Feuillade, who went on to direct Fantômas and Les Vampires.

She also experimented with sound. Contrary to popular belief, The Jazz Singer in 1929 was not the first film with synchronized sound. Gaumont and Alice Guy began creating sound films in 1902 with their patented invention, the Chronophone.

To make these early sound films, popular singers were recorded on a gramophone. Then they were filmed lip-synching to their recording. The audio and the visual would then be synchronized together with the Chronophone. Gaumont believed this was the next step in filmmaking and threw all of the studio’s resources into marketing the invention. Alice Guy directed and produced 150 sound films to demonstrate the Chronophone.

The Gaumont Films

Twitter/CitizenScreenAlice Guy on the set of The Life of Christ, in Fontainebleau, France, in 1906.

Guy’s films are refreshing for their wit and sly feminism. In Madame’s Cravings (1907), a pregnant woman is bent on satisfying her cravings — even if she has to steal from children and homeless people. In The Drunken Mattress, a maid inadvertently sews a drunkard into a mattress and then struggles to lug it across town. In The Consequence of Feminism (1906) gender roles are lampooned 14 years before women could vote.

Her magnum opus for Gaumont was The Life of Christ (1906). The ambitious film was based on a lavishly illustrated Bible by the artist Jacques Tissot and told the life of Christ through the viewpoint of several women. At 33 minutes long, it was one of the first films using multiple reels stitched together.

The film also featured 300 extras and some of the first examples of special effects.

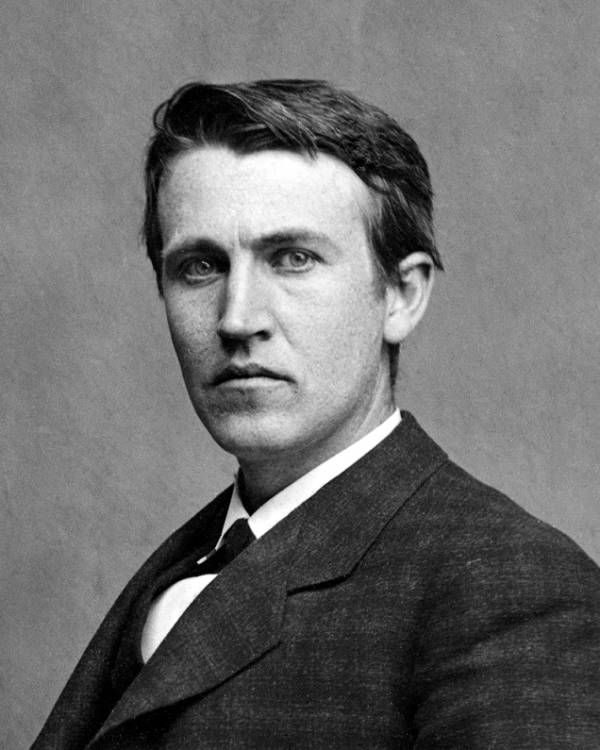

Alice Guy-Blaché’s Rivalry With Thomas Edison

Library of Congress/Wikimedia CommonsThomas Edison, circa 1878. Age 30.

In 1907, Alice Guy married Herbert Blaché, a cameraman for Gaumont nine years her junior. She resigned from her position to accompany her husband to Cleveland, Ohio, where he had been sent to promote the Chronophone. The business failed to take off and they retreated to Gaumont’s studio in Flushing, New York. There, they learned that Thomas Edison was the cause of their problems.

Edison held hundreds of patents on film stock, motion picture cameras, and projectors. In 1908, he created The Motion Picture Patents Company (MPPC) to control distribution, production, and exhibition of films. It turned out that Edison had a competing sound film process and he was not happy about the Chronophone. Through the MPPC, he was icing Gaumont out of distribution. With no way for Gaumont films to be sold or seen, the studio languished.

Alice Guy-Blaché finally decided she’d had enough of the stalemate. In 1910, she founded Solax Studios and took over an under-utilized New York facility. Solax began cranking out two one-reelers per week. To date, Guy is the only woman to have owned a movie studio.

Alice in Filmland

Solax became the largest pre-Hollywood studio in America. In two years, the company outgrew the facility in Flushing. Guy-Blaché went across the Hudson River to Fort Lee, New Jersey, where she helped establish a filmmaking community. She built a $100,000 state-of-the-art studio that included five sound stages, carpentry shops, dressing rooms, administrative offices, labs, dark rooms, and projection rooms.

Guy oversaw more than 300 productions at Solax and directed at least half of the films. Her Solax films include A House Divided (1913), a comedic marital spat featuring a hilariously insubordinate secretary. She also made the first film with an all-Black cast, A Fool and His Money (1912). As films became longer in length with more complex storytelling, Guy followed suit making films like the 42-minute action-fantasy Dick Whittington and His Cat (1913).

Alice Guy-Blaché’s Final Reel

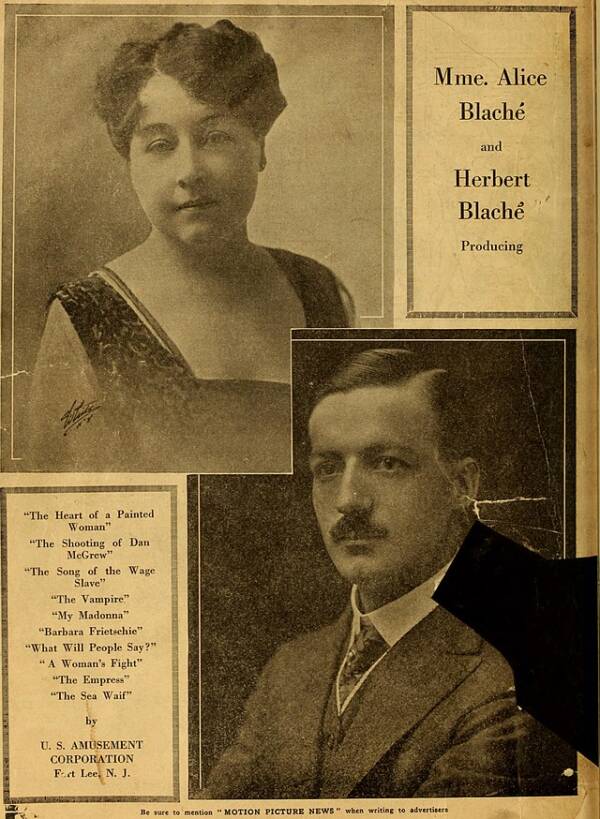

Wikimedia CommonsAlice Guy Blache and her Husband, Herbert Blache.

Solax Studios began to falter with the start of World War I. Coal rationing resulted in no lights and no heat. French companies like Gaumont left America and Solax was forced to seek funding elsewhere. They began leasing their studios to other film companies like the nascent Metro-Goldwyn Mayer.

But many of the film companies were leaving. The MPPC had a stranglehold on film production on the East Coast. Filmmakers had to adhere to Edison’s stodgy rules and pay licensing fees for every piece of equipment they used. If they balked, Edison sent lawyers to hound them with litigation. Chafing at the restrictons, filmmakers fled to southern California, where the MPPC’s lawyers didn’t operate.

Alice Guy-Blaché was part of the exodus. By 1918, the Guy-Blaché marriage was on the rocks. Blaché had started a competing filmmaking company that encroached on Solax Studios and eventually dominated it. He finally left for Hollywood with another woman.

That year, while directing her last film, Tarnished Reputations, Alice Guy-Blache became ill with the Spanish Influenza. Four of her Solax employees died of the same sickness and it took her months to recover. Then, part of Solax Studios burned down. Exhausted and in debt, Guy declared bankruptcy. She auctioned off what remained of Solax Studios and returned to France in 1922.

Wikimedia CommonsA still from Guy-Blache’s final film, Tarnished Reputations.

Back in France, Guy couldn’t find work as a filmmaker. After five years of chasing investors and following up leads, she returned to the United States to obtain copies of her films to demonstrate her abilities. She was devastated to find that all of her work had disappeared. She couldn’t find any prints — even when she visited the Library of Congress, where her films had been copyrighted. With the advent of talking pictures a few years later, it became clear that she would never direct another film.

For the rest of her life, Guy fought against being erased from history. She wrote articles, spoke at film institutes, and corrected historians who credited someone else — usually a man — for her work. In 1954, Gaumont’s son Louis gave a speech in Paris about her contributions. A small flurry of interest ensued and she was decorated with a French Legion of Honour in 1953.

Guy died at the age of 94 on March, 24, 1968, in a nursing home in New Jersey. Even after her memoirs were published seven years after her death, she remained largely forgotten. It was only around the year 1995 that book-length studies on her work and several documentaries began to appear. To date, out of the thousand films that she directed and produced, only about 100 have been found. In her memoirs, Guy reflected on her life, “It is a failure; is it a success? I don’t know.”

Now that you’ve learned about Alice Guy Blaché, find out about William Desmond Taylor And The “Crime Of Passion” That Shocked Early Hollywood and enjoy Early 20th Century Paris In Amazing Color.