The walls depict lessons about the importance of respecting one's elders but do so through some grim means.

Chinese Cultural RelicsThe 700-year-old tomb was first discovered by archeologists in 2012.

Archaeologists in Yangquan, China discovered a tomb which dates back 700 years to when the descendants of Genghis Khan ruled over China. While no skeletons were found within the tomb, researchers determined that it once belonged to the bodies of a couple — a husband and wife.

A painting of them can be seen on the northernmost wall of the tomb.

Chinese Cultural RelicsThe husband and wife who would have been buried in the tomb are depicted here at a table with writing instruments.

One can imagine that life under the rule of descendants of Genghis Khan was not easy. While eventually, the Chinese were able to reclaim their territory in 1368, the tomb reveals a glimpse into what exactly life was like in Mongol-era China.

The unique octagon-shaped tomb also features a pyramid-shaped roof with walls adorned by murals of the sun, moon and stars.

Chinese Cultural RelicsThe octagonal-domed roof within the tomb.

The murals seem to depict life and values in Mongol-ruled China, including a band of musicians, tea being prepared, and horses and camels transporting people and goods. Archeologists detailed their findings in a report published in the journal Chinese Cultural Relics in early August 2018.

But not all of the murals display such pleasantries. Indeed, some paintings reveal a more sinister way of life in Mongol-ruled China.

One of the murals tells the commonly told urban legend of the time about parents who chose to bury their young son alive in order to feed a dying parent.

Chinese Cultural RelicsThe story of Guo Ju depicts the sacrifice of a couple’s son in order to help their sick mother.

The legend goes that Guo Ju and his wife were forced to decide between caring for their sick mother or for their young son, with little food and money to spare. They ultimately decided to bury their son alive so that they could have enough resources to care for the mother instead.

But this story — believe it or not — actually has a happy ending. When the parents were digging the hole for their son they found gold coins, which was viewed as a reward from heaven for caring for their mother. Now supplied with enough money to care for both their mother and their son, there was no need to sacrifice the boy.

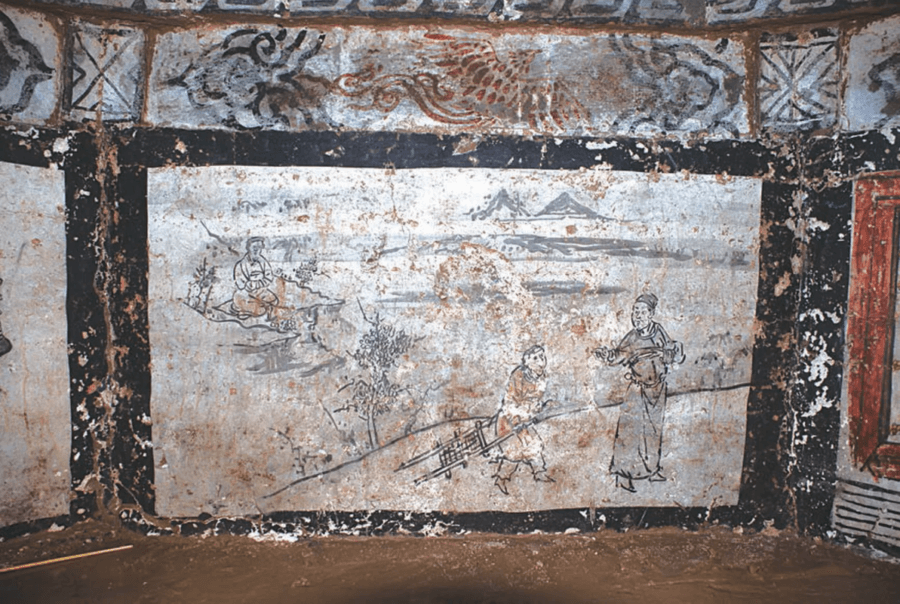

In a different mural, a similar story of sacrifice is depicted. It tells the story of a family with a young child, Yuan Jue, who were suffering in a grave famine. The father decided to wheel the grandfather off into the woods to die so that the rest of the family would have a better chance of survival.

But young Jue protested and told his father that he would do the same to him when he became as old as the grandfather. So the father gave in to Jue’s threat and the entire family miraculously survived the famine.

Chinese Cultural RelicsThe famous Chinese story of Yuan Jue teaches the importance of respecting your elders.

Researchers noted that both stories display the importance of “filial piety” in Chinese culture, or the importance of respecting one’s parents and grandparents. So although both tales are relatively dark, they ultimately teach the immense value of respect.

Beyond these macabre allegories, researchers also discovered evidence of segregation in Mongol-ruled China.

Some scenes depicted characters in Mongol-style ensembles rather than in mainstream Chinese fashion. One of the men in the murals is seen “wearing a soft hat with four edges, which was the traditional hat of northern nomadic tribes from ancient times,” the archaeologists note.

The difference in clothing is believed to be motivated by, and evidence of, segregation. The archeologists wrote in their report:

“Mongol rulers issued a dress code in 1314 for racial segregation: Han Chinese officials maintained the round-collar shirts and folded hats, and the Mongolian officials wore clothes like long jackets and soft hats with four edges.”

The murals reveal the hardships, rules, and values of this slice of time in China’s long history. Oddly enough, historical records also suggested that there was an increase of “dragon sightings” during this period, but the Mongol-era tomb shows no such thing.

Regardless, the stories of unanimous Chinese values, like xiao, or filial piety are wonderful revelations about the culture’s essence then into now.

Next check out these facts about Genghis Khan. Then, read about Xin Zhui — the most well-preserved mummy in history.