From communal wiping sponges to vermin-infested sewers, learning about ancient Roman bathrooms will make you glad that you live in modern times.

Karen/FlickrA Roman bathroom in Ephesus, near present-day Selçuk, İzmir Province, Türkiye.

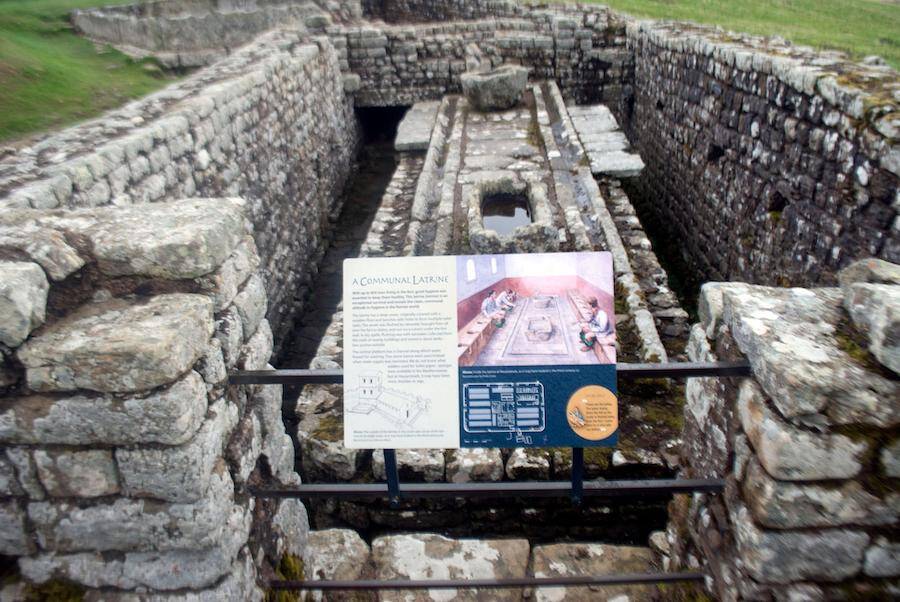

Known as foricae, Roman public bathrooms were practical facilities where the non-elites could relieve themselves in ancient times. The foricae were open in design, with stone slabs featuring evenly spaced holes for seating — just inches apart. While the setup might sound intrusive, it was integral to the cleanliness of public spaces, at least by ancient standards.

Often built near public baths, foricae were constructed over a stream of running water, which carried waste away from Roman cities and into nearby rivers. To wipe themselves, foricae visitors used a tersorium — a sea sponge on a stick. Since users didn’t know how diseases spread, the tersoria were likely used and re-used by everyone who entered the facilities.

The foricae were part of the Roman Empire’s larger sanitation effort, which included aqueducts and sewer systems, like the famous Cloaca Maxima of Rome. Despite their flaws, these public toilets and Rome’s early sewer systems represented a groundbreaking approach to urban waste management. However, that didn’t mean they were good for public health.

How Did The Roman Public Bathrooms Work?

kat/Flickr The design of ancient Roman bathrooms was open and social.

The ancient Romans had a strict system for taking care of their waste. Among the non-elite classes of Rome, public toilets that were connected to an early sewer system were available for people to do their business and even converse with fellow city dwellers if they wished. Many examples of these ancient bathrooms existed across the Roman Empire.

These Roman toilets, called foricae, were specifically built for the poor and enslaved in ancient Rome, so the elites wouldn’t have to see the lower classes urinating and defecating in the streets. And so the bathrooms were most often used by male laborers, merchants, and slaves.

Typically, foricae were housed in a dimly lit building with a low ceiling. The bathrooms often featured slabs of marble along the walls, with holes cut into the stone for people to sit. Though the holes were spaced inches apart, they allowed most to relieve themselves in a comfortable, seated position.

While this may seem incredibly invasive, some experts have argued that the foricae may have actually afforded more privacy than the average urinal.

“Today, you pull down your pants and expose yourself, but when you had your toga wrapped around you, it provided a natural protection,” Ann Olga Koloski-Ostrow, an anthropologist at Brandeis University, said in an interview with the Smithsonian Magazine. “The clothes they wore would provide a barricade so you actually could do your business in relative privacy, get up and go. And hopefully, your toga wasn’t too dirty after that.”

Wikimedia Commons/CC BY 3.0A tersorium, a sea sponge on a stick that was used for wiping in a Roman bathroom.

The holes were placed above a small stream of water, often fed by an adjacent public bathing facility. This water would “flush” the waste out of the foricae and into Rome’s sewer system. However, the open layout of the toilets — and the fact that there was usually filth left behind in the bathrooms — attracted vermin like rats and spiders. Users often risked being bitten by creatures that crawled up from the dirty conduits below.

When one was done with their business, they would often use a tersorium to wipe. The tersorium was simply a sea sponge attached to a stick, and the tersoria were likely used by everyone in the foricae. Sometimes dipped in vinegar or salt water for sanitation, the tersorium provided people with a way to clean themselves long before the invention of toilet paper. In some cases, people used other methods for wiping, like ceramic discs called pessoi.

Communal wiping methods meant that if one user was infected with a disease that affected their bowels, it was likely that everyone else who used the same wiping tool would also be infected. Even if they didn’t use a wiping tool, they also risked infection from the marble they sat on — after all, since the buildings were so dimly lit, some people were bound to miss the holes.

After cleaning themselves as best as they could, foricae users would either dip their hands in an amphora full of water or simply go about their day. Though the foricae helped keep Rome’s streets relatively clean, the spread of disease continued to be a pressing issue, and the conditions at the foricae often led elites to steer clear of them — unless it was a dire emergency.

What Do The Ancient Toilets Tell Us About Roman Social Hierarchy?

Public Domain Ancient Roman bathrooms in Ostia Antica.

Historians emphasize that ancient Roman public bathrooms were almost exclusively for the non-elites. Instead of sharing a space with the common folk, the upper classes would use private latrines in their own residences.

Additionally, chamber pots allowed elites to relieve themselves in their villas or workplaces with minimal smell left behind. Slaves would be forced to empty and clean these pots, often throwing their contents into a garden.

Though upper-class people were the ones who ordered the construction of the foricae and paid for them to be built, they clearly did not want to be associated with the public bathrooms, as they refused to inscribe their names into the latrines to identify themselves as the benefactors.

For laborers, merchants, and slaves, the foricae were often the only options they had to use the bathroom. Though Roman public bathrooms weren’t technically separated by gender, users were mostly male, with only a few women (most of them slaves) going to the foricae if they really needed to.

Gary Wilkinson/Alamy Stock PhotoRemains of a communal latrine at the Housesteads Roman Fort, located near Hexham, Northumbria, England.

“Public latrines were constructed in the areas of the city where men had business to do. Maybe [an enslaved] girl who was sent to the market would venture in, out of necessity, although she would fear being mugged or raped. But an elite Roman woman wouldn’t be caught dead in there,” Koloski-Ostrow explained to the Smithsonian Magazine.

Surprisingly, for some foricae visitors, the ancient toilets weren’t solely a place to relieve themselves, but also a spot to socialize and discuss politics, sports, and gossip. Ancient games have even been found at some sites.

Foricae have also revealed Romans’ spirituality. At some sites, researchers have discovered incantations warding off evil and dedications to deities. Whether these symbols were meant to protect people from the horrors of life in general or the risks of the foricae is still, by many accounts, unclear.

Roman Restrooms And The Development Of Early Sewer Systems

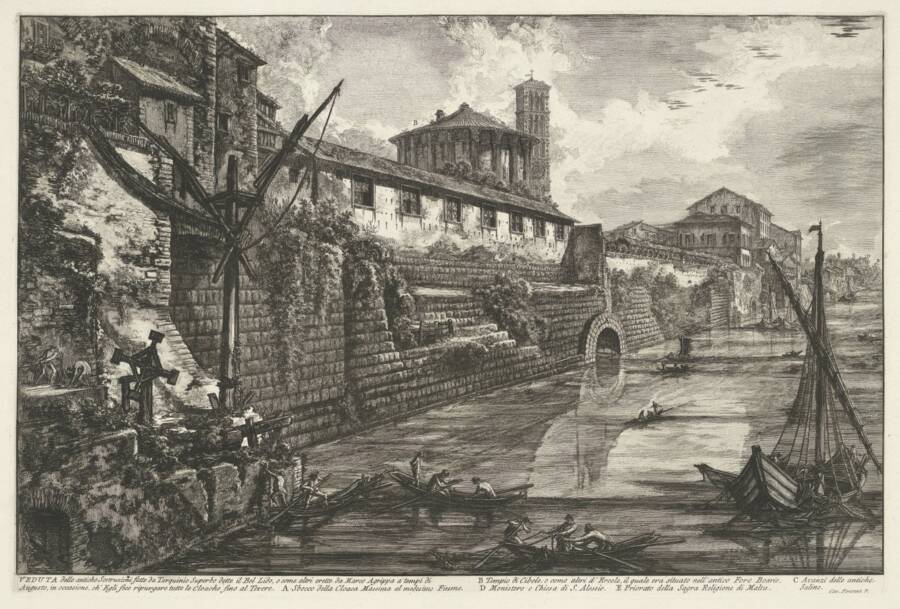

Public DomainAn 18th-century illustration of the outlet of the Cloaca Maxima sewer in Rome.

The ancient Roman bathrooms were part of a larger, sophisticated public sanitation network. With up to tens of thousands of residents in a single Roman city, it was necessary for officials to keep human waste in check.

Alongside the building of foricae, Roman cities also constructed aqueducts and sewer systems in order to minimize public health scares.

In the city of Rome, which was home to a whopping 1 million residents at its height in ancient times, sanitation was at the forefront of city planning.

Beginning around 600 B.C.E., Rome started constructing the Cloaca Maxima, a massive and complex sewer system. The system was initially an open channel, but it was eventually enclosed with a stone barrel vault. Over time, the system was connected to public baths and latrines via early sewers.

By the late Roman Republic, the Cloaca Maxima stretched 1,600 meters. Manholes were eventually added and 11 aqueducts connected to the system. Incredibly, some parts of Cloaca Maxima are still in use today.

Despite Cloaca Maxima being ahead of its time, it did not come without issues. While it did remove waste from the city, the sewer system was ultimately unable to fully control the hazards of waste. Without thorough sanitation of both the city’s residents and their facilities like the foricae, health issues continued to be a massive societal problem.

As Koloski-Ostrow memorably put it: “Think about it — how often does someone come and wipe off that marble?”

After reading about ancient Roman public bathrooms, learn what it was like to use the toilet during the medieval period. Then, find out why gong farmers had one of the most disgusting jobs in world history.