These nocturnal poop collectors of Tudor-era England spent their time knee-deep in cesspits full of human excrement.

On moonlit nights during the Tudor period of Wales and England, darkened silhouettes would toil below the castle. They were the “nightmen,” digging and scraping near the walls before shuffling into the distance. By name they were the “gong farmers” — by trade, they were removing human excrement from castle cesspits.

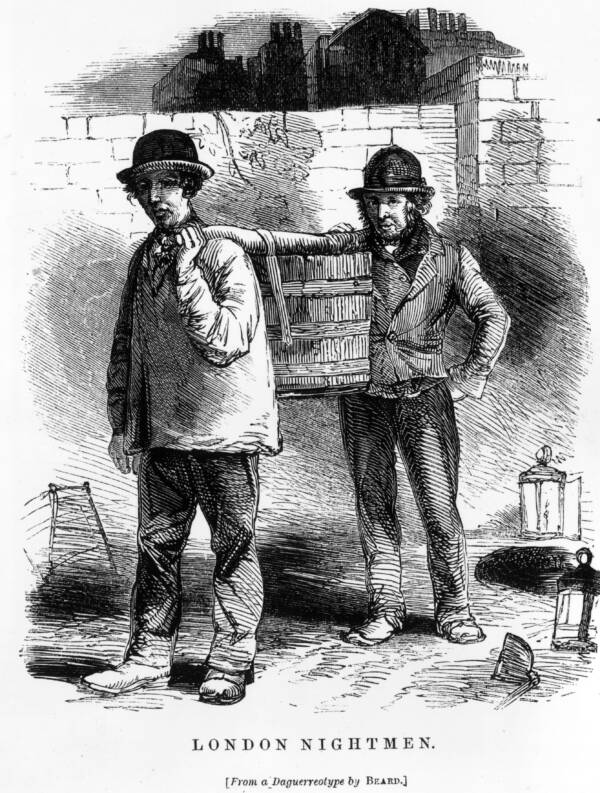

Hulton Archive/Getty ImagesAn 1849 illustration of two nightmen as published in London’s The Morning Chronicle.

“Gong” was Old English for both the fecal matter and medieval toilet repository, itself. Gong farmers were to work only at night. They emptied a castle’s collective cesspit every two years, but also accepted payment for individual privies, as well. They toiled for two shillings per ton — centuries before indoor plumbing arrived.

The History Of The Gong Farmer

In order to properly appreciate a gong farmer’s line of work, an understanding of his instruments is crucial. While only a bucket and able-bodied colleague were needed, some nightmen required a carriage. After all, their task was carrying tons of waste to the town boundary, with the distance varying in each case.

Medieval Europe had morphed into a disjointed collection of feudal territories as a result of the fall of Rome in 467 A.D. Most were satisfied to survive on the land, while the more fortunate lived in castles with toilets scattered about. Understanding the mechanisms of a medieval toilet was naturally vital for a gong farmer.

Since the flushing toilet wouldn’t be invented until 1596 and only become somewhat standardized in 1851, the medieval toilet was a rudimentary design that used gravity to its benefit. With a circular opening built into the castle stone and wooden bench atop, the medieval “garderobe” was similar to an outhouse.

Flickr/IsabelToiletgoers simply wiped themselves with hay and splashed a bucket of water into the toilet — with gong farmers tasked to do the rest.

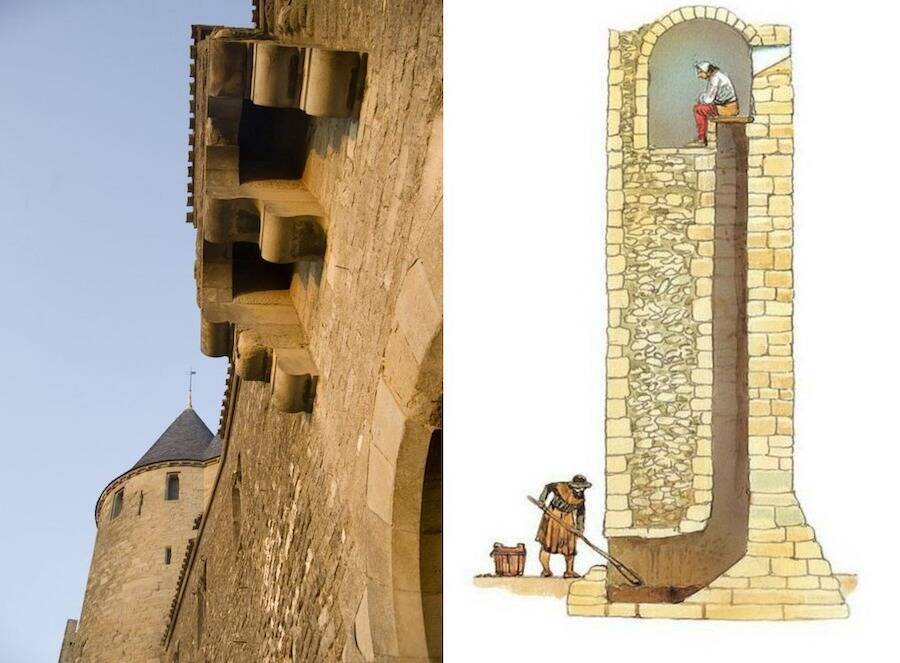

Some sat on the edges of a castle, with plenty of forts in London built for human excrement to fall right into the Thames below. More landlocked castles used garderobe chutes, or shafts running along the interior of a castle wall, to funnel the waste into a collective cesspit below — where the work of a gong farmer began.

Communal outhouses outside, or “house of easement,” demanded the same duty. Posing newfound health concerns, any festering excrement was to be removed and transported to designated dump sites beyond a town boundary. Castle cesspits could take years to fill, while private privies required more regular attention.

Built less than airtight, these cesspits allowed for any liquid to drain, That left behind metric tons of solidified human excrement — or “night soil” — for gong farmers to remove. From around 9 p.m. to 5 a.m., they emptied the pits and carted off fecal matter as its leisurely donors slumbered.

How The Nightmen Toiled

Up to three or four men were often required for the job, with one shoveling the feces into buckets, another pulling those up with a rope, and the rest carrying those loads onto their cart. With medieval toilet chutes a precarious opening for enemy invaders, gong farmers were often asked to thwart any attackers if possible.

It wasn’t uncommon for gong farmers to bring their young practitioners along. With their small size and nimble bodies, small boys were able to maneuver around these small spaces with ease. In addition to cleaning out the actual pit, these stool farmers were also expected to wash out the chutes leading into it.

While any valuable items like jewelry that fell into these toilets surely cropped up on occasion and made for a fine surprise, gong farmers largely relied on actual farmers who paid handsomely for the feces — as it made for excellent natural fertilizer for their crops. However, the work itself appeared rather well rewarded.

University of Reading/FacebookA medieval toilet jutting out from the castle (left) and the interior chute funneling its contents to the gong farmer below (right).

Payment for the gong farmer varied across the Middle Ages. Historical records from the 15th century show two shillings (or $90 today) were standard. Some accounts even detailed payment in pounds of candle wax — while a gong farmer for Elizabeth I was purportedly paid in brandy.

As laborers covered in the years-old feces of others, gong farmers were designated to live in certain areas. Their work was exhausting, with no ventilation in these cesspits allowing reprieve during the night-long job. Perhaps most famously, gong farmer Richard the Raker drowned in a pit whose ceiling had rotted in 1325.

In the case of Newcastle Castle, the fort was largely abandoned by the 1500s with enough excrement to fill 30 modern-day shipping containers left behind. In the end, human innovation did away with any need for a gong farmer. With indoor plumbing spreading around the world in the mid-1800s, the nightmen joined the rest of the world — and spent their nights in bed.

After learning about the medieval gong farmer, read about modern Americans working more than medieval peasants did. Then, learn about 10 medieval execution methods that define cruel and unusual.