When Andrew Jackson died in 1845, 150 enslaved laborers lived and worked at his Nashville estate, the Hermitage.

Brent Moore/FlickrAndrew Jackson’s Nashville estate, the Hermitage.

More than 300 enslaved individuals worked and lived on the grounds of the Hermitage, former U.S. President Andrew Jackson’s sprawling estate in Nashville, Tennessee, in the early 19th century. Historical records indicate that over two dozen of these people died at the Hermitage and were buried on the property, but decades of efforts to locate their graves were unsuccessful.

Recently, an anonymous donor revitalized the hunt for these burial sites by providing a generous donation to pay for aerial imaging, ground penetrating radar, and the hours of labor required to pore over historical documents. These efforts paid off in January 2024 when the research team discovered 28 graves marked by subtle ground depressions and limestone slabs.

Now, the Andrew Jackson Foundation is exploring ways to preserve and honor the memories of these individuals to recognize their integral roles in the history of the Hermitage.

The History Of Andrew Jackson’s Tennessee Estate

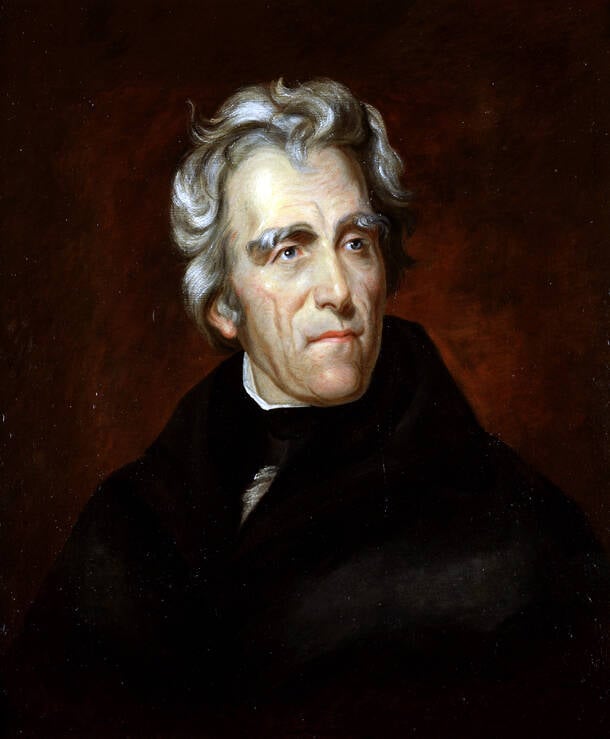

Public DomainAn 1857 portrait of Andrew Jackson, the seventh president of the United States.

Andrew Jackson was the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before he was elected, he studied law, and he settled in what was then the frontier town of Nashville in 1788 to work as a prosecuting attorney.

In 1804, Jackson purchased 425 acres of land in the area and built an estate called the Hermitage. At the time, he had nine enslaved laborers. He even took some of them with him to the White House when he became president. When Jackson died in 1845, the estate had expanded to more than 1,100 acres with 150 enslaved workers.

Historians know that at least two dozen of these laborers died at the Hermitage, but attempts over the decades to locate their final resting places were unsuccessful.

“Any time you have this large of a population of enslaved people at the site, there has to be a cemetery somewhere,” Tony Guzzi, the chief of preservation for the Andrew Jackson Foundation, told The New York Times. “This was really the one glaring missing thing.”

Efforts to find the burial site finally paid off in January 2024 when researchers combing the grounds of the Hermitage located 28 graves on the property.

Discovering A Lost Burial Ground At The Hermitage

Brent Moore/FlickrThe quarters at the Hermitage where enslaved workers lived.

The process of finding the graves began with an anonymous donor who wanted to help the Andrew Jackson Foundation tell a more complete history of slavery at the Hermitage. They gave the organization money to search for burial sites.

Then, while combing through historical records, researchers discovered a key piece of information. A 1935 agricultural report mentioned a specific area near a creek on the property that would not be suitable for farming because there were bodies buried there.

Using old maps and aerial images, researchers then narrowed their search area down to five acres. They began walking the land to look for signs of the cemetery. One day, while searching a patch of overgrowth about 1,000 feet from the quarters where the enslaved workers once lived, they spotted a few small limestone slabs and a series of depressions in the ground.

To prevent damaging the suspected burial site, the researchers used ground penetrating radar to examine the area. They discovered a total of 28 graves, each measuring about six feet by two feet. These findings matched the historical records of reported deaths of enslaved individuals at the estate. Finally, researchers had found a cemetery.

Brent Moore/FlickrAnother memorial for 60 enslaved people from a nearby plantation buried on Hermitage property.

Now, the foundation is discussing the next steps for the graves. They can either exhume and study the remains or leave them undisturbed and build a large memorial instead. At the moment, visitors can view the burial ground from a distance and read the names of the enslaved people buried there on a plaque near the site.

According to a press release from the foundation, a final report is expected in 2025. Hopefully, ongoing research will reveal more information about the lives of the people buried in the graves, connecting us with the largely untold stories of American history.

“We tell you about slavery, we have exhibits about slavery, we have tours that talk about slavery,” said Guzzi. “But it’s all kind of in the abstract. This is the one place, I think, where people can have a tangible connection — you’re there where enslaved people are buried. That’s real.”

After reading about the graves of enslaved workers found at Andrew Jackson’s estate, go inside the story of Andrew Jackson’s assassination attempt. Then, read about the complicated history of when slavery actually ended in the United States.