The newly dated fossil suggests humans migrated out of Africa far earlier than we thought.

When a broken skull was excavated from a limestone cliff in the Apidima cave in Greece in the 1970s, experts didn’t fully understand what they’d found, and stored it in a museum in Athens. Now, according to The Guardian, a new analysis has now found the skull fragment to be the oldest human fossil ever found outside of Africa.

Published in the journal Nature, the research estimates that the partial skull is at least 210,000 years old. If accurate, that claim would force a significant rewriting of human history. Apidima 1, as the skull is called, would predate the oldest known Homo sapiens fossil in Europe by more than 160,000 years.

The ramifications here would indicate human migration out of Africa occurred much earlier than previously thought.

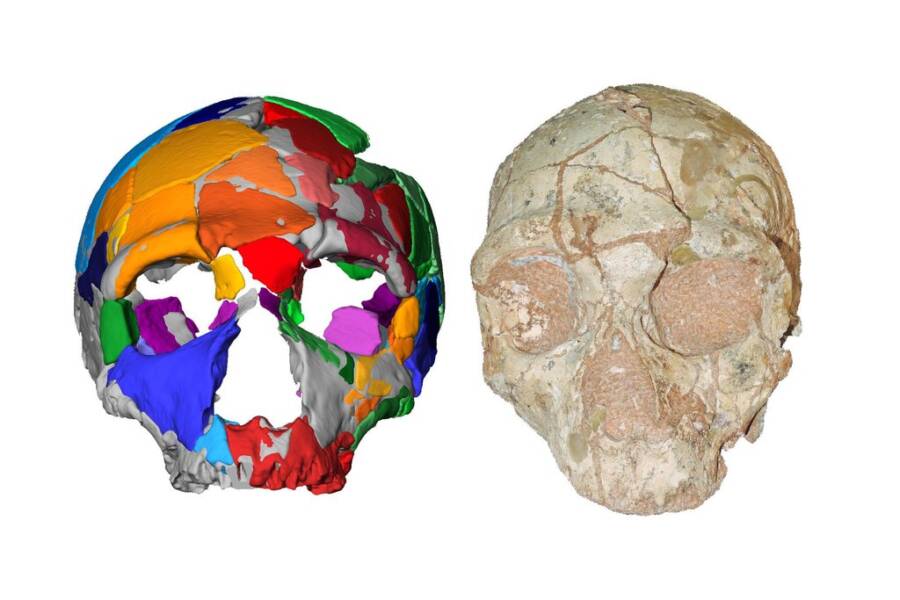

Katerina Harvati, Eberhard Karls University of TübingenThe Apidima 1 fossil was found to be at least 210,000 years old, predating the previously oldest human fossil found outside of Africa by over 160,000 years.

All humans who have ancestry outside of Africa descend from one group of Homo sapiens who emigrated 70,000 years ago. But that wasn’t the first human migration out of Africa.

In recent years, scientists have uncovered fossils in Israel and elsewhere that are much older than 70,000 years — like a 180,000-year-old jaw bone found last year. These came from what scientists believe were earlier, failed migrations. Perhaps humans were overtaken by Neanderthals, or suffered a natural disaster.

But this skull fragment is the oldest human fossil found outside of Africa — and four times older than the previous record-holder for the oldest fossil in Europe, which dated back to 45,000 years ago.

For the director of paleoanthropology at the University of Tübingen, Katerina Harvati, this find clears the proverbial board: “Our results indicate that an early dispersal of Homo sapiens out of Africa occurred earlier than previously believed, before 200,000 years ago,” she said. “We’re seeing evidence for human dispersals that are not just limited to one major exodus out of Africa.”

Not everyone in Harvati’s field is convinced of the data here, however. Some experts seem unwilling to accept this new theory, as it would wipe away decades of research. The main counterpoint is that this skull is unlikely to belong to an early Homo sapiens species, and probably belongs to a Neanderthal.

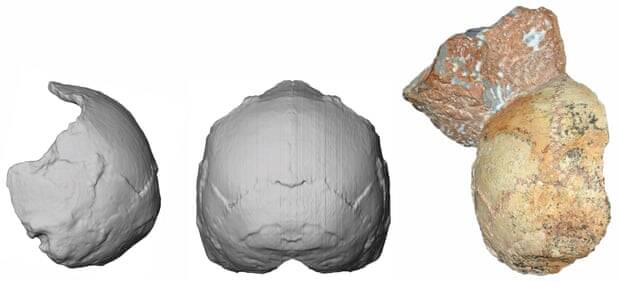

Katerina Harvati, Eberhard Karls University of TübingenThe Apidima 2 was found to be at least 170,000 years old and that of a Neanderthal.

But Harvati and her colleagues believe the fragment’s curvature points to it having belonged to the back of a human skull.

The newly dated fossil has had a long, decades-old journey to arrive at the point of published theory. Discovered in the Apidima cave in southern Greece in 1978, it was so damaged that it was relegated to an Athens museum to gather dust.

A second skull found during the dig did get analyzed thoroughly, as it retained a complete face and seemed to be a promising find. This fossil, named Apidima 2, turned out to belong to a Neanderthal — and thereby didn’t have any earth-shattering consequences regarding the timeline of early human migration.

Harvati and her team decided to examine them both, nonetheless. By taking CT scans of the two skulls, they were able to create virtual 3D reconstructions that they could precisely compare with skulls from early Homo sapiens, Neanderthals, and modern humans.

What they found with the second skull was that it had a pronounced, round brow ridge that confirmed it as Neanderthal. The other one, however, appeared strikingly similar to that of a modern human — with the most notable evidence being the skull’s lack of a Neanderthal bulge on the back the head.

Katerina Harvati, Eberhard Karls University of TübingenKaterina Harvati and her team used CT scans to create virtual 3D models of the two fossils, and then compared them with fossils of Neanderthal, Homo sapiens, and modern humans.

“The part that is preserved, the back of the skull, is very diagnostic in differentiating Neanderthals and modern humans from each other and from earlier archaic humans,” Harvati explained.

To cover their bases using all the modern technology at their disposal, Harvati’s team took advantage of the radioactive decay of natural uranium that occurs in buried human remains, and traced how much has vanished to gather an estimated date range.

They found the Neanderthal skull to be at least 170,000 years old, while the Homo sapiens skull dated back a minimum of 210,000 years. The rock that encased the two skulls was found to be over 150,000 years old. Researchers posit that the two artifacts may have mixed together after a mudflow encased them and then solidified.

Some scientists are skeptical, including Spanish paleoanthropologist Juan Luis Arsuaga and University of Wisconsin-Madison paleontologist John Hawks.

“The fossil is too fragmentary and incomplete for such a strong claim,” said Arsuaga. “In science, extraordinary claims require extraordinary proofs. A partial braincase, lacking the cranial base and the totality of the face, is not extraordinary evidence to my mind.”

“Can we really use a small part of the skull like this to recognize our species?” Hawks asked. “The storyline in this paper is that the skull is more rounded in the back, with more vertical sides, and that makes it similar to modern humans. I think that when we see complexity, we shouldn’t assume that a single small part of the skeleton can tell the whole story.”

For Harvati, however, the physical attributes — and the fact that Neanderthal fossils in Europe have been found to contain human DNA — are enough to at least strongly consider her theory. As it stands, she’s fairly convinced, and suggests more research and data-gathering be done in Greece to confirm or disconfirm her hypothesis.

“It’s eerie how well it all fits,” she told The New York Times. “If there’s an overarching explanation, my guess would be a cultural process. This is a hypothesis that should be tested with data on the ground. And this is a really interesting place to be looking at.”

After learning about the oldest known human fossil ever found outside of Africa, read about some Pacific Islanders having DNA that links to no known human ancestor. Then, learn about the oldest-ever bracelet being found alongside an extinct human species.