Some biblical archaeologists believe that a slew of ancient female figurines could very well represent an early Judeo-Christian Goddess named Asherah, the wife of God.

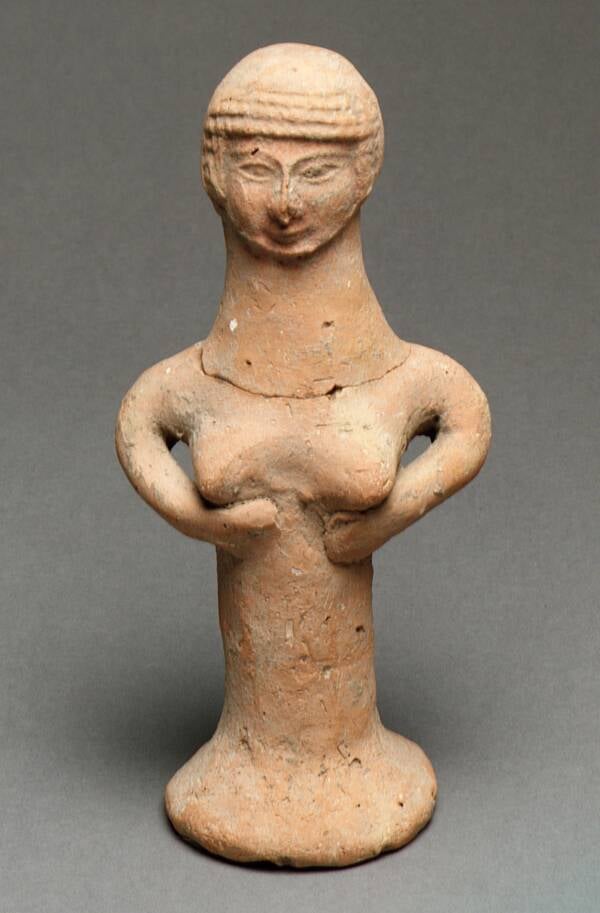

Wikimedia Commons.A terra-cotta figurine of Asherah from Judah.

The ancient Middle East had plenty of gods and goddesses, so what’s discovering one more going to mean for our history?

Well, if the deity in question happens to share an altar with God Himself, then 2,000 years of orthodoxy is up for grabs. Indeed, if the early Israelite religion from which the monotheistic traditions of Judeo-Christianity were borne included the worship of a Goddess named Asherah, how would that change our reading of the Biblical canon and the traditions that produced it?

Could Asherah Really Be God’s Wife?

In the richly historical land known as the Levant — roughly, Israel, the Palestinian Territories, Lebanon, and Syria — a wealth of information about how people lived in some of the pivotal eras in the human story has been discovered.

For instance, numerous female figurines from roughly 1000 B.C. to just after 600 B.C., when the southern kingdom of Judah fell to the Babylonians, which may have represented the wife of the early Hebrew God.

These clay sculptures, roughly conical in form, depict a woman with her hands cupping her breasts. The head of these statuettes falls into two patterns: either crudely pinched to create minimal features, or bearing a characteristic medium length hairstyle and more naturalistic facial features. The figurines are always found broken, and always in a place indicating disuse.

Public Domain“Nude female figure,” from the site Tell ed-Duweir / Tel Lachish of historical Judah in modern Israel. Circa 800-600 B.C.

No one can say for sure what purpose the figurines served, why they’re prevalent, or why they were destroyed — if they were. They may have been a secular object or even children’s toys. But a prevailing theory is that these represent some of the very images that so troubled the prophets: an equal to the God of all gods, his wife, and queen consort, Asherah.

While there’s no question that Judaism was monotheistic by the time the Hebrew Bible was considered complete, the discovery is troubling because the presence of a female deity, if, as some scholars have come to believe, that’s what the statuettes represent, contradicts the narrative that ancient Israelite religion was entirely consistent with the religion of their ancestors, all the way back to the figure of Abraham, whose life story was taken as literal truth.

In the eras of the Temples at Jerusalem, priestly roles were held by men. Likewise, under most of the history of the Rabbinic tradition women were excluded. With the exceptions of Mary, the mother of Jesus, and the disciple Mary of Magdala, the Christians too reserved sacred positions in the canon for men. Also, the Tanach, known to Christians as the Old Testament, records a succession of historical patriarchs and a male political leadership but lists women in several cases as prophets as well.

But the potential widespread worship of Asherah would suggest that these religions were not always patriarchal.

Perhaps more importantly, in their long-codified forms, Judeo-Christian traditions are also all monotheistic, but the worship of Asherah would suggest that they were not always or that they became so gradually.

What Asherah Would Mean For Monotheistic Traditions

Before strict monotheism became the rule in Israel, an older tradition of polytheism practiced by the Canaanites held that there was one patron deity who was but the most powerful of many gods throughout the Hebrew-speaking region.

In the earliest Hebraic traditions, this deity was named “El” and this was also the name of the God of Israel. El had a divine wife, the goddess Athirat of fertility.

When the name YHWH, or Yahweh, came to be used to denote the primary God of Israel, Athirat was adopted as Asherah.

Modern theories suggest that the two names El and Yahweh essentially represent the merger of two previously distinct bands of Semitic tribes, with the Yahweh worshippers coming to predominate.

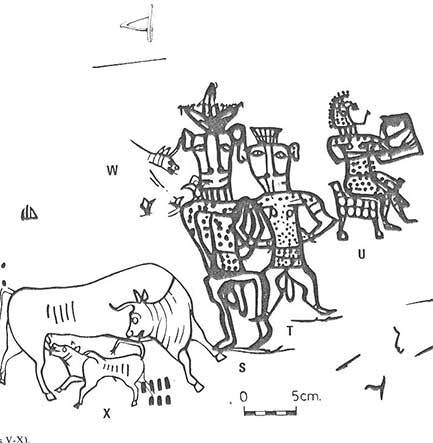

Wikimedia CommonsLine drawing of the images on one of the Kuntillet Ajrûd potsherds.

There was pressure, then, upon the faction of El followers to conform to the Yahwist position and to abandon what came to be seen as backward Canaanite practices, such as worshipping at an outdoor grove or hilltop altar or worshipping multiple gods. As such, the disparity in religious beliefs came to pit the Canaanites against the Israelites.

But several finds in the mid-twentieth century indicate a cultural continuity between these two groups, for instance, that both may have believed their patron God of gods had a wife.

Indeed, the evidence of these shared traditions between the Israelites and Canaanites hints at an older tradition which afforded less exclusive power to men and a singular God, at least in terms of imagery, than originally thought in this patriarchal and monotheistic religion.

Uncovering The Evidence

For instance, in 1975 at the site called Kuntillet Ajrûd, which was likely occupied for about a hundred years around 800 B.C., a number of devotional objects that feature the God of gods, Yahweh, beside what many have argued could be the Goddess Asherah, have been discovered.

These included two large yet destroyed water jars, or pithoi, and a number of murals.

There were also a number of potsherds or broken pieces of pottery, which in the days long before paper manufacture, were a common writing surface. If it was unwieldy, perhaps just a few notes or a doodle could be put down on the potsherds. On two potsherds here, though, surprising messages stand out:

“… I bless you to Yahweh of Samaria, and to his Asherah.” (Or “asherah.”)

“…I bless you to Yahweh of Teman and to his Asherah.”

The meaning of the word Teman, a place name, is uncertain, and deciphering ancient epigraphs are challenging even to scholars. But a formulaic expression seems quite clear here.

Archaeologist William Dever, author of Did God Have a Wife?, asserts that this message suggests that just as Asherah was the consort of El in the Canaanite religion, she might have remained the partner to Yahweh when His name became the prevailing title for the God of gods.

Dever further speculates that one of the figures in the potsherd drawing, which may have been etched by someone other than the author of the text, may be Asherah herself, seated on a throne and playing a harp. This is an interesting idea, but one that would require additional context for verification. He does point out that the site likely served some ritual purpose, as attested by the devotional artifacts.

However, it seems likely that the drawing above the inscription was added later and it could be that the drawing and inscription are therefore unrelated.

At another site from the 700s B.C., Khirbet El-Qôm, a similar epigraph appears. Archaeologist Judith Hadley translates these hard-to-read lines in her book The Cult of Asherah in Ancient Israel and Judah: Evidence for a Hebrew Goddess.

“Uriyahu the Rich wrote it.

Blessed be Uriyahu by Yahweh

for from his enemies by his asherah he has saved him

by Oniyahu

by his asherah

and by his a[she]rah.”

Some words are missing, but the blessing seems to be based on the same then-current formulaic expression.

If a longer inscription emerges somewhere in the archaeological record, it might clarify whether the stock expression is about a ritual object or God’s wife. For now, experts disagree. But half a century ago, when the fragments first emerged, almost no one was having the conversation in the first place.

That’s in part because biblical archaeology began as a field devoted to collecting evidence that corroborated existing scripture. But by the late 20th century, the focus of the study had in large part shifted to a secular exploration of the Bronze and early Iron Ages during which era these biblical paradigms were created.

But it became less common to find artifacts that literally mirrored scripture than it was to find artifacts from everyday life that in some ways outright contradicted the canon, as in this case, the discovery of the potential wife to a monotheistic deity.

So Who, Or What, Exactly Was Asherah?

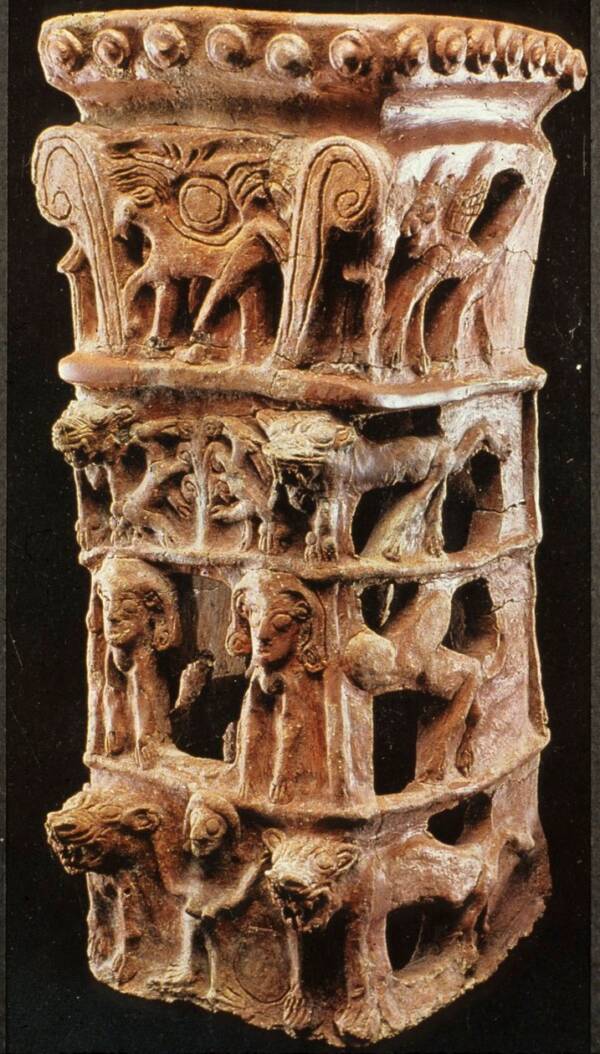

Wikimedia Commons“Model Shrine” from 9th century B.C. Lion figure on top may be related to worship of Asherah. From the collection of the Israel museum.

The word “Asherah” appears in the Hebrew Bible 40 times in various contexts.

But the nature of the ancient texts makes the use of the word, which literally means something like “happy,” ambiguous. Was “asherah” an object meant to represent a goddess, did it denote a class of goddess, or was it the name of the Goddess Asherah Herself?

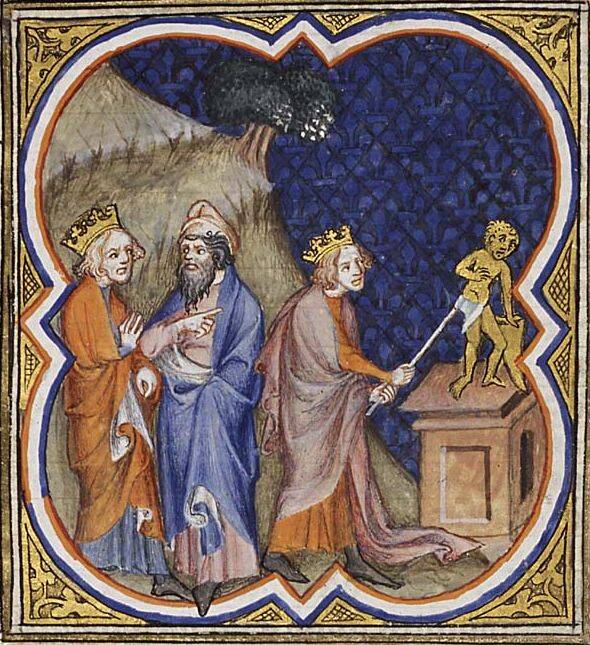

Wikimedia CommonsThe Jewish king Asa destroys the idols of polytheists in favor of the worship of one true God, YHWH.

In some translations, Asherah is taken to refer to a tree or grove. That usage reflects a chain of associations. Trees, often connected to fertility, had been considered a sacred symbol for the nurturing figure of Asherah. In a related sense, “an asherah” could refer to a wooden pole, effectively an indoor stand-in for a tree.

In fact, when it became less fashionable to worship various gods, including the Goddess Asherah, followers used an asherah pole, or asherah’s tree, in her stead to pray covertly.

One interpretation of the Garden of Eden story could be a repudiation of female-centered fertility or maternity cults, and the forbidden Tree of Knowledge could relate to practices like the devotion to Asherah, or the use of an Asherah.

Traditional Biblical scholarship explains that placing an asherah next to an altar of the God of Israel was intended as a sort of extra sign of devotion and was fairly commonplace. Indeed, some scholars interpret these dual idols at a place of worship as corresponding to Yahweh/El and Asherah together.

Doing this, however, eventually became a violation of religious law, as it insinuated polytheism — even if the asherah was meant to honor Yahweh and no one else.

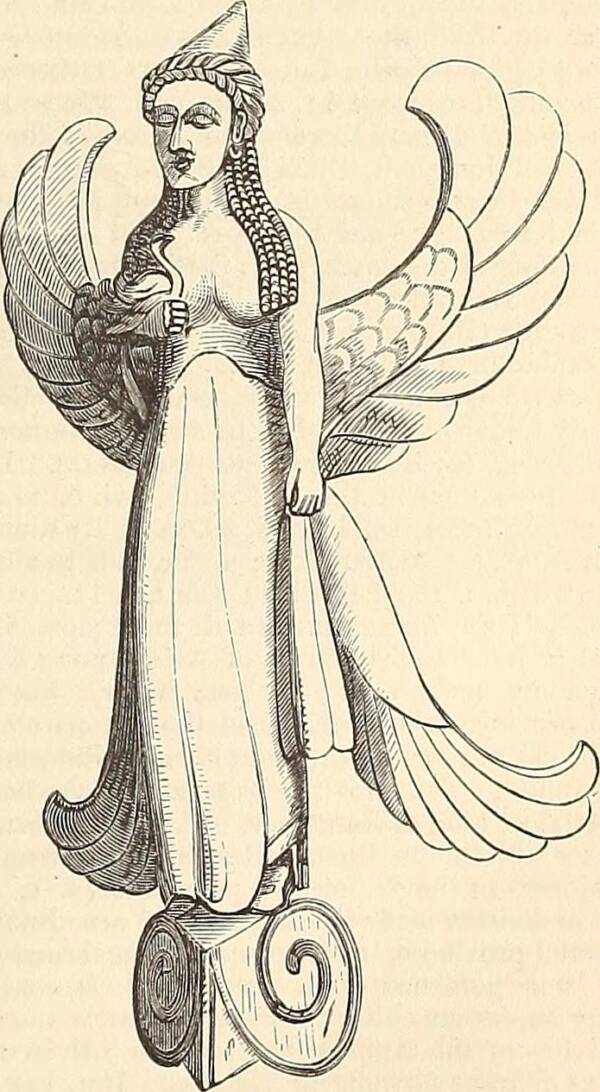

Getty ImagesMother Goddess Astarte (Asherah), relief on ivory of a goddess between two mountain goats, Ugarit, Syria. Ugaritic Civilisation, 14th century BC.

It’s also possible, however, that what started out as a symbol of the Goddess lost its original meaning and simply came to be seen as a sacred object.

Elsewhere in the Hebrew scripture, “asherah” seems to refer explicitly to a prohibited Canaanite deity. Much of the knowledge archaeologists have about Canaanite beliefs comes from a site called Ugarit, north of the Israelite territory, but speaking a language closely related to Hebrew.

In Ugaritic, “Asherah” is written as “Athirat” and is said to have been a goddess and consort to El, the patron God of all gods in the polytheistic Canaanite religion, possibly including the god Ba’al, who would himself later supplant El as the chief deity among the later Canaanites.

The goddess also exists in the complicated mythological schemes of related cultures in the region, including the Hittites, and in some varieties has 70 children.

Wikimedia CommonsThis terra cotta altar in the shape of a city gate is adorned with an image of a tree and female figures thought to be Asherah, ca. 1000-800 B.C. Researchers identify this and other objects found at the archaeological site including many, mostly female figurines, as devotional, but the specific religion practiced is unclear.

But the idea that an asherah — or a clay female figurine — might actually be an icon for a Goddess named Asherah didn’t really start to gain traction until the 1960s and 70s and especially based upon the discoveries and analysis by Dever.

Why Don’t Juedo-Christians Recognize God’s Wife Today?

Most of the ancient Israelites were farmers and pastoralists. They lived in small villages with their extended family where adult male children would stay in the same household or a structure adjacent to their parents.

Wikimedia CommonsThe tree and female figurines incised on the facade of the center figurine as well as the righthand tree figurine are thought to represent Asherah. From the collection of the Israel museum. The ritual chalice on the left was found next to it.

Women would move to a new village when they married but it would be close by. Compared to the lush riverine civilizations of Egypt and Mesopotamia, the living could be rough in the semiarid Levant. There were a very few rich landowners and most people would have simply survived if they were lucky.

In the era of the Israelite monarchies, most religious practices took place in these villages, the countryside, and the home. And, as is the case with modern religious practice, personal beliefs didn’t necessarily fit the official doctrine — which is itself subject to change.

That said, scripture focused on the ancient upper class: the kings and their entourages, as well as the religious elite in the major towns and cities, especially Jerusalem. And it was the choice of these ruling elites which religious traditions were to be practiced or forgotten.

Public DomainA drawing of Ashtoreth, originally another Canaanite deity, but conflated with Asherah in scholarship, Biblical texts, and possibly in popular worship too.

As such, it wasn’t unusual for the Bible to be revised in order to reflect the prevailing political agenda in Jerusalem at a given time. The Book of Genesis, for instance, contains writings and revisions from several eras, and not in order of composition.

Therefore, as polytheism gave way to monotheism, albeit with some overlap it seems, the faction of El to the followers of Yahweh, so too did the worship of Asherah become lost to time.

© The Israel Museum, Jerusalem/Israel Antiquities Authority/Avraham Hay.Four-tiered cult stand found at Tanaach is thought to represent Yahweh and Asherah. Asherah, a mother goddess, was the consort of El, the chief deity in the pre-monotheistic Canaanite pantheon.

Eventually, then, the use of an asherah in the Temple of Jerusalem or the worship of Asherah, would have gone out of fashion perhaps around the 600s B.C., coinciding with the end of the production of female clay figurines.

Israelite religion only became centralized under monotheism after a long period of regional variations. Meanwhile, the worship of Asherah eventually fell so out of fashion that even her legacy was lost to history for a time. But the notion that the God of gods in the definitively monotheistic tradition could have once had a wife is certainly a tantalizing one.

After this look at God’s wife, Asherah, see what 500 American Christians think God looks like. Then, read about why some historians think the ancient Sumerians were once visited by aliens called the Annunaki.