From ancient China to Mesoamerica, dragon legends are ubiquitous across dozens of cultures across the world.

You’ve never seen a dragon.

Not in real life, anyway. But you know exactly what they look like. These monsters — evocative of a misty, legendary past — are with us so much and so often that they might as well be real. Certainly they get more press than many real-life fantastic beasts that actually walk the earth.

Of course, long before Hollywood movies made CGI dragons the embodiment of evil (as in Lord of the Rings) or humans’ favorite companions (How to Train Your Dragon), word of mouth, supplemented by the occasional illustration in a book or scroll painting, was sufficient to keep the legend alive.

And therein lies the question scholars of mythology have sought to answer: Even with the endless variations of language and culture that people have created — not to mention every possible type of landscape and climate they’ve called home — time and again, our ancestors have conjured up the myth of the dragon.

It’s as if, in our wanderings, the great winged reptile glided silently behind us, adapting itself to its new circumstances, just like the mammalian bipeds it followed.

Lands Of The Dragon

Jacques Savoye/PixabayA Chinese dragon in Shanghai. Notice the precious pearl in its mouth.

China has the longest continuous tradition of dragon stories, dating back more than 5,000 years.

In Chinese imagery, dragons symbolize imperial rule and good fortune. The dragons of Chinese legend dwelled in distant waters, and although usually wingless, they could fly. Crucially, they brought the rain, and hence the fruits of the soil. In the 12-year Chinese zodiac, dragon years are the most auspicious.

Hugely popular as the forms for puppet-costumes in New Year celebrations, boats in festive races, ornamentation on buildings, and myriad other uses, dragons remain as current a symbol in modern China as they did thousands of years ago.

And much of the dragon imagery in other Asian countries, particularly Japan and Vietnam, adapts designs long ago influenced by the Chinese. But if that continuity is straightforward to trace historically — like Zen Buddhism and the Kanji script, other cultural mainstays borrowed from China — other cultural parallels are harder to explain.

In addition to the medieval dragons of Europe, fabulous dragon-like monsters show up in folklore of the American Indians of the North American plains, and the Maya and Aztecs, most famously as the plumed serpent god Quetzalcoatl.

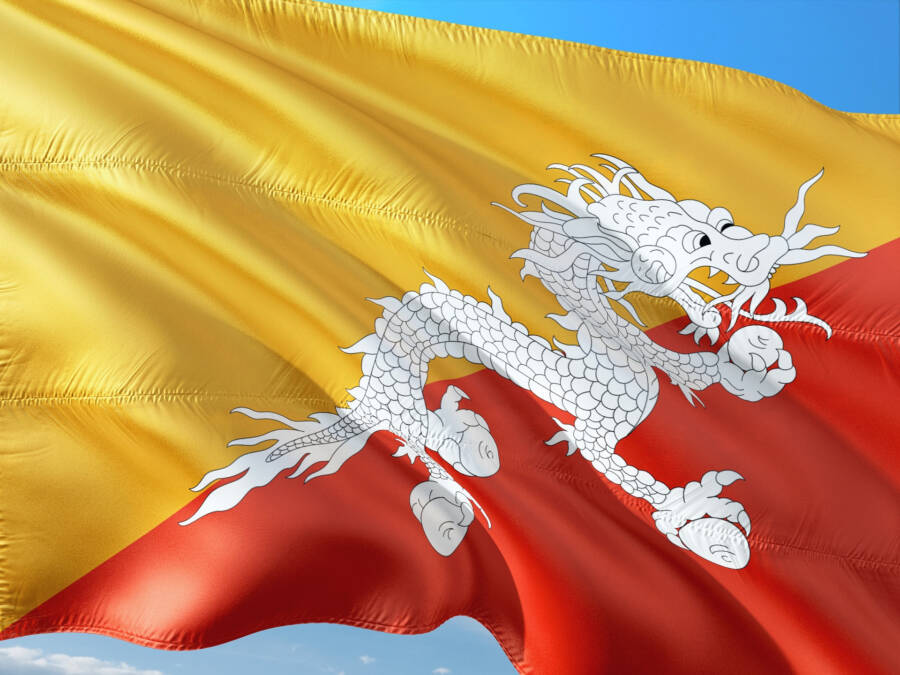

PixabayThe thunder dragon on the flag of Bhutan, a small nation in the Himalayas.

India and its South Asian neighbors also have ancient dragon traditions. One even appears on the flag of the small Himalayan nation of Bhutan. Those who stretch the definition of a dragon a bit can even find one in the legends of the Inuit in Canada’s Arctic regions.

So where did everyone get this idea?

Dragon Origin Stories

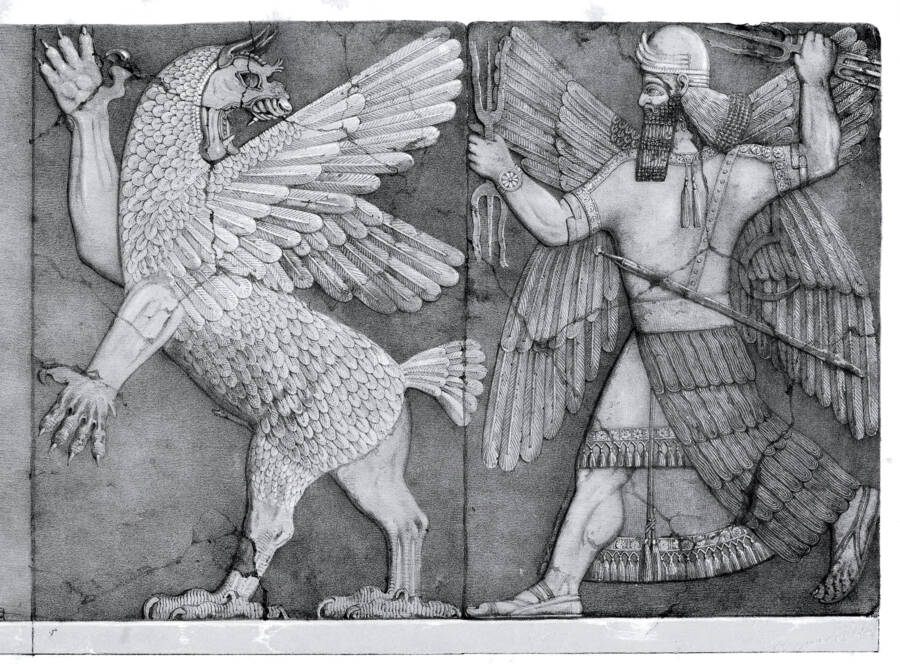

Mesopotamian stories of monster battles are the best candidates for the earliest writings about dragons.

In the Babylonian version, a serpentine deity-monster called Tiamat emerged from the sea to threaten all of creation with a return to primordial chaos. The heroic young god Marduk takes up the challenge, slaying Tiamat and rescuing the cosmos.

Wikimedia CommonsThe ancient Babylonian creation myth of Tiamat (left) dates to at least the second millennium B.C.

As with other Mesopotamian myths, the Bible contains echoes of this battle. Among other references, the Psalms and the Book of Job tell how the God of Israel vanquished the Leviathan, which is something like a cross between a whale and a snake.

Variations on the story of Tiamat will show up many times in the Mediterranean and European traditions. The opposition of a dragon or similar monster and a heroic savior forms one of the key aspects of Western dragon myths. In many cases, the dragon exists only so that the hero has something to slay.

Greek mythology includes several battles with serpent-monsters as well. Zeus secures his rule over the heavens and Earth by using his thunderbolts to kill Typhon, the fire-breathing dragon creature with snakes for legs. The Greeks’ Typhon myth follows an earlier storyline borrowed from neighboring civilizations, including the Hittites.

That the Greek word drakōn gives us the English word “dragon.” But the ancient Greeks seemed to use their word to mean something more like a big snake, so it isn’t a perfect translation.

The word drakon, in term, comes from a verb meaning “to watch,” and the connection becomes apparent in the story of Jason and the Golden Fleece.

This precious but heavy piece of outerwear was under the constant guard of a sleepless dragon. Jason’s significant other, Medea, is skilled in folk pharmacology, and so they manage to get the giant creature to doze off for a bit. Such Greek myths contain additional motifs familiar to the canonical dragon cycle — in this case, the characteristic of dragons as jealous guards of a golden treasure.

Completing The Picture

Wikimedia CommonsIn this 13th-century illustration, St. George slays a dragon that demanded human sacrifices.

From Tiamat and Perseus, it’s only a short jump to the standard dragon story of the medieval West: the legend of St. George.

In the legend’s classic form, a venom-breathing dragon terrorizes the Libyan city of Silene. Over time, its required tribute goes from animals to humans, and, inevitably, the princess of the land.

St. George rides into town on his horse and, learning of the people’s plight, agrees to kill the dragon as long as everybody there converts to Christianity. They do, and he does, thereby providing a template for endless medieval illustrations.

The narrative seems to have assembled itself from various sources. In late antiquity, a popular subject for pre-Christian devotion in the Balkans showed a rider on a horse, which was often rearing up on its hind legs, sometimes spearing an animal, or sometimes beside a tree around which a snake curled itself.

Wikimedia CommonsIn this fourth-century ancient Egyptian sculpture, the god Horus slays Set, who’s in the form of a crocodile. The setup is very similar to depictions of the myth of St. George, though it predates the myth by about 800 years.

In the Christian era, these soldiers gave way to images of unnamed militant saints in the same pose, but now killing a snake. The change reflects a shift in attitudes toward snakes. No longer associated with life and healing, snakes, through interpretation of the New Testament, became a visual shorthand for evil.

St. George was born in Cappadocia, in modern-day Turkey, in the third century A.D. Tradition holds that he was a soldier, refused to practice pagan worship, and might have burned down a Roman temple, for which he was martyred. But for centuries, there was no connection between him and any kind of dragon story.

Sometime after the year 1000, St. George emerged as the protagonist in a text from, perhaps appropriately, the country of Georgia, which, like England, considers the saint its patron.

Crusader knights spread the legend of St. George from the eastern Mediterranean to Western Europe, where the St. George story took its place as a mainstay of the medieval imagination.

If you add in the characteristic of breathing fire from the Typhon story, this suite of symbols: a captive princess, a dragon, a knight, a battle, plus some kind of reward, would remain current in stories told in the European world down to the present.

Comparative Mythology

Wikimedia CommonsThe Mesoamerican deity, Quetzalcoatl, which in some myths is a dragon-like reptile.

So there’s a lot of source material bouncing around different cultures in the Western tradition, with a fairly clean path from ancient times connecting ancient Asian dragons with their present-day successors.

But how did these two general currents, let alone all of the parallel traditions around the world, converge on a single image?

Mythologist Joseph Campbell, following the early theorist of psychology, Carl Jung, pointed to a shared inner experience that people inherit: the collective unconscious. Perhaps the dragon symbol is just one of the basic images people recognize without being taught.

A recent variation on the idea of hardwired imagery draws on animal behavior studies.

In his book, An Instinct for Dragons, anthropologist David E. Jones proposed that over millions of years, natural selection imprinted upon our primate ancestors a recognition of the form of the dragon.

The basis for his theory is that vervet monkeys automatically react to snakes, instinctively, and show similar responses to images of big cats and birds of prey.

Among our common ancestors, individuals with an instinctive aversion to things that can kill you will, on average, survive longer and produce more offspring. Dragons, Jones suggested, represent a collage of the crucial attributes of the ultimate predators: wings of large birds of prey, jaws and claws of big cats, and the winding bodies of snakes.

Critics note that Jones’s theory requires more data to be proved or widely accepted, but it’s a compelling theory nonetheless.

Mistaking Dinosaurs For Dragons

PixabayA dragon statue on a bridge in Ljubljana, the capital of Slovenia.

In The First Fossil Hunters, historian of science Adrienne Mayor presented as an alternative examples of folk paleontology in ancient texts. People started finding fossils long before they had any way to make sense of geological time, but that didn’t prevent them from trying to explain their extraordinary discoveries.

An isolated femur from an extinct population of European elephants could inspire speculation about giant human-like creatures. But more complete skeletons from dinosaurs, or the knobby skull of a prehistoric giraffe, could lead an ancient traveler to extrapolate the body of an animal similar to a dragon.

The writers of natural histories from the classical world, such as Herodotus, were then faced with the task of sifting through secondhand accounts, with some tolerance for reports of strange animals, but more skepticism toward odd hybrids.

In a way, the dragons-are-ubiquitous theory is kind of circular. Western and Asian dragons are very similar in appearance, but not identical, and their mythical roles tend to be even more distinct. The functions of the Mesopotamian dragons are different, as well.

Some dragons seem aquatic, but the canonical European dragon isn’t. Quetzalcoatl is even more of a stretch. When the word “dragon” appears in the Hebrew Bible, it’s a translation, based upon a decision that the creature in question can fit into the category. Translations differ widely in such judgments. And moreover, it was not an inevitable choice to translate the Chinese word lóng as dragon, either.

Dragon Planet

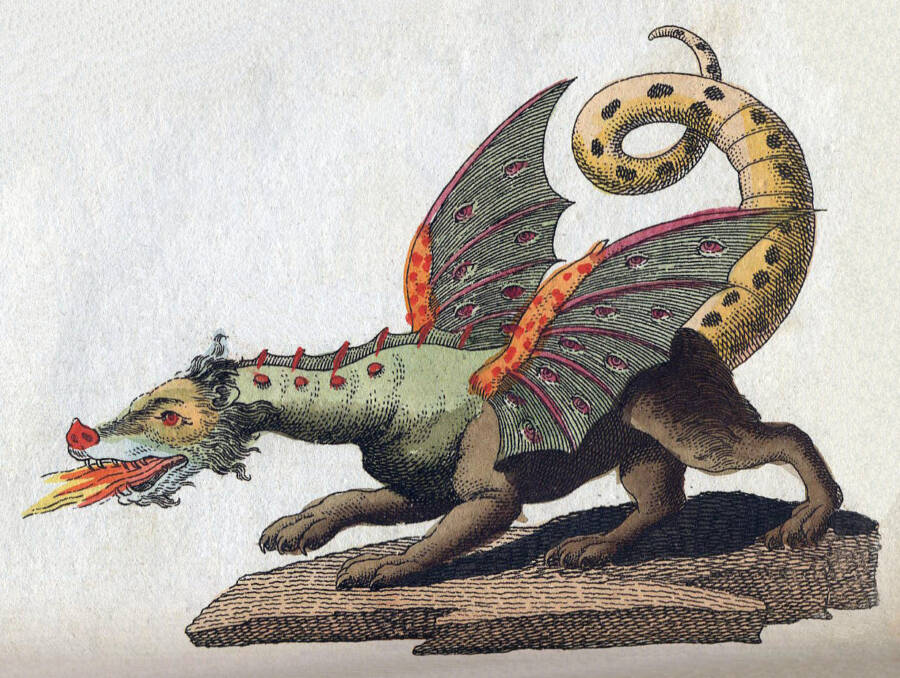

Wikimedia CommonsA dragon illustration by German publisher Friedrich Justin Bertuch. 1806.

But at least one academic is considering the theory that the dragon trope is really, really old.

Michael Witzel, a Harvard University scholar of Sanskrit, proposed that two branches of culture among early Homo sapiens diverged along lines of settlement and migration, and brought their distinctive dragon myths with them.

Based on genetic evidence, one earlier stratum followed a southern migratory route across Asia, Indonesia, and Australia, while a second supergroup diverged to populate most of Eurasia and the Americas. By his logic, the makings of the earliest dragon myths — the Asian ones being mostly benevolent, with the Eurasian and American ones being mostly malevolent — date to as far back at 15,000 years ago.

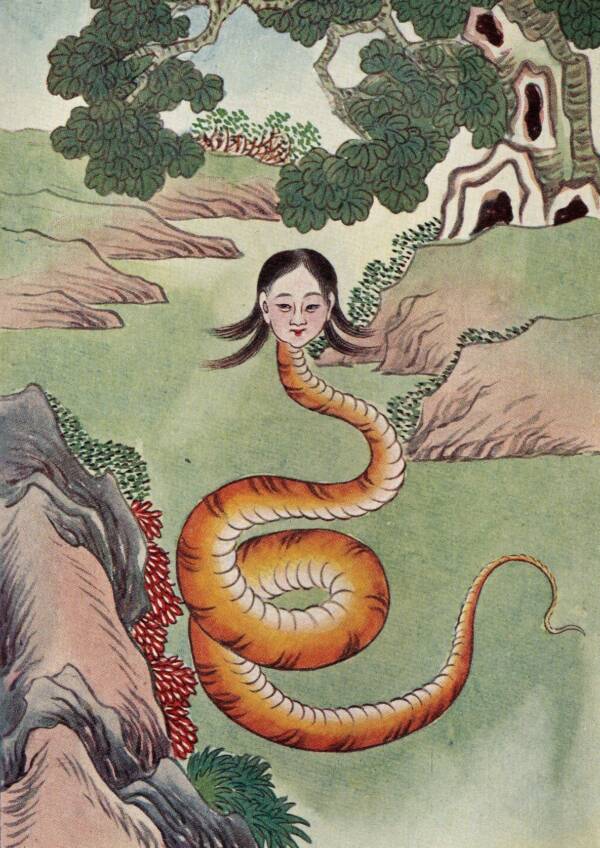

Here it’s worth noting two exceptions to the benevolence characteristic of the Asian dragons. Several episodes from the Chinese creation myth involve Nüwa, a mother goddess with the head of a human, and like her consort, Fu Xi, the body of a snake.

After order of the heavens and Earth were established, a restless dragon named Gonggong rebelled and brought chaos upon the land. Nüwa repaired the cosmic damage to an extent, ensuring the safety of the human beings she’d created. Of course Nüwa and Fuxi were both serpentine themselves, and the havoc from Gonggong stands in contrast to the beloved dragons most familiar from Chinese lore.

Wikimedia CommonsThe Chinese goddess Nüwa, who cleaned up China after a dragon’s mess, had the head of a human and the body of a snake.

A story of one of Japan’s founder deities has perhaps an even more striking parallel to the dragon legends of other countries.

Susano’o, a storm god, happened upon an elderly deity couple who were distraught. Yamata no Orochi, a giant eight-headed, eight-tailed serpent had devoured seven of their daughters, and was going to come for their last, Kushinadahime. Susano’o agreed to save the couple’s daughter if he might marry her.

The couple gave their assent, and Susano’o hid Kushinadahime by transforming her into a comb, which he placed in his hair for safekeeping. He then gave instructions to the couple to prepare enough sake, in eight separate containers, to intoxicate all of the serpent’s heads, making it possible for him to kill the monster.

Within the body of Yamata no Orochi, Susano-o discovered a precious sword, which became one of the symbols of Japan’s rulers.

Certainly, even if they haven’t been around since the beginning of the world, or even 15,000 years, dragons have some serious staying power as an object of fascination.

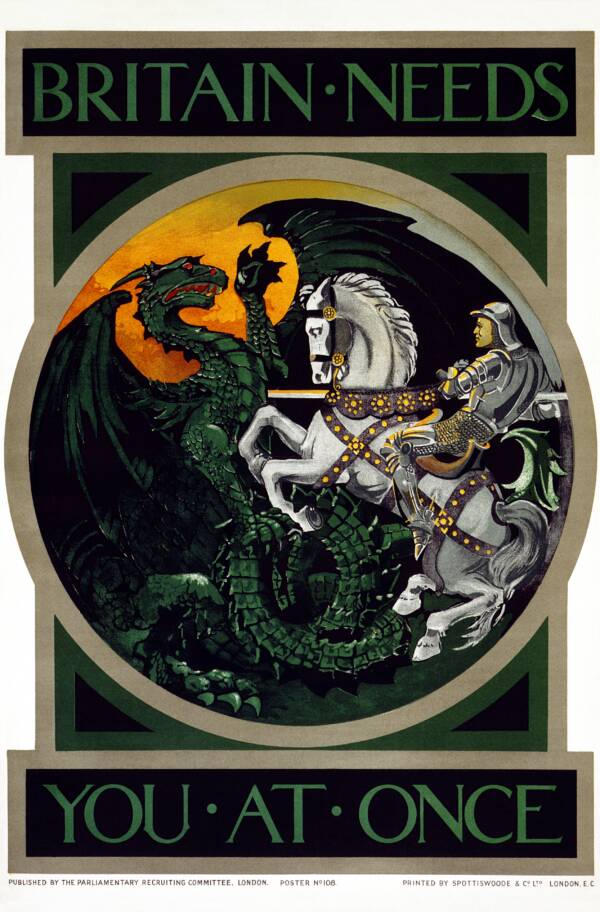

Wikimedia Commons“Britain needs you at once,” reads a British army recruitment poster from World War I, depicting a soldier slaying an evil dragon.

After delving into the history of dragon myths, check out these 11 mythological creatures that expose humanity’s worst fears. Then read about Scathach, the legendary warrior woman of Ireland.