Domestic and feral cats along with invasive foxes have contributed to the extinction of at least 25 mammals once native to Australia.

Department Of Parks And Wildlife/South Coast Region, Albany, AustraliaCats in Australia kill 252 million mammals per year.

When foxes were introduced into the Australian wilderness in 1845, they were released for leisurely sport hunting. Cats, meanwhile, have given millions of Aussies unconditional companionship. According to new research, however, the two predators kill 2.6 billion animals per year — driving many species to extinction.

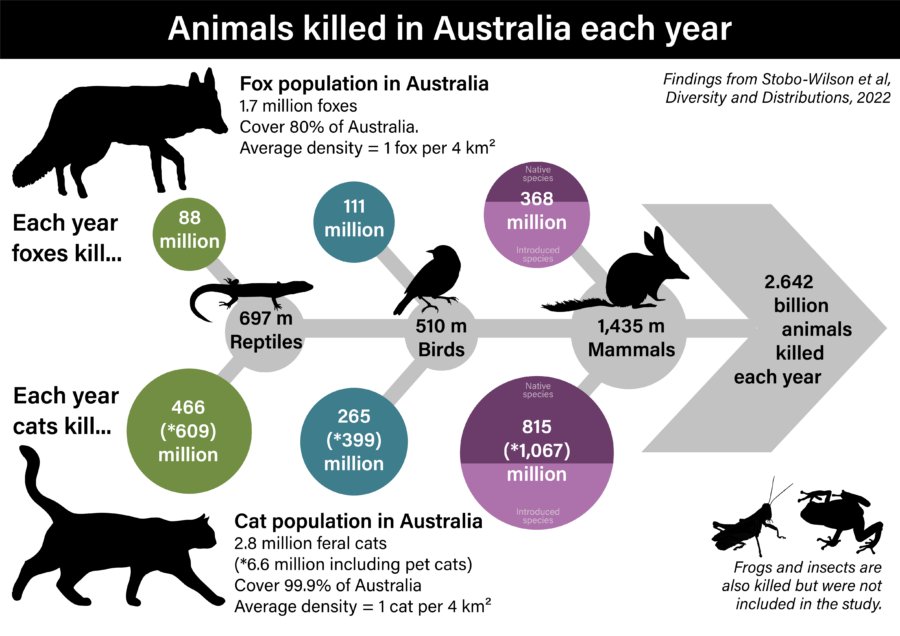

This predation annually eliminates 697 million reptiles, 510 million birds, and 1.4 billion small mammals. Domestic cats alone are killing 500 million animals per year. This trend, centuries in the making, is spurring the decline and extinction of several species.

“This enormous death toll is one of the key reasons Australia’s biodiversity is suffering major declines,” the study’s authors wrote in The Conversation.

“Cats and foxes, for example, have played a big role in most of Australia’s 34 mammal extinctions, including the desert rat-kangaroo which rapidly declined once foxes reached their region,” they continued.

Published in the Diversity and Distributions journal, the study was led by Dr. Alyson Stobo-Wilson of Charles Darwin University. It alarmingly detailed how cats and foxes are decimating Australian wildlife and how essential it is to manage these predators — before a whole variety of unique creatures vanishes forever.

Centre for Invasive Species SolutionsFoxes in Australia kill over 300 million native mammals per year.

Cats are just as non-native to Australia as foxes and were brought to the continent by colonizers in the 1800s. At least 100 unique flora and fauna species have been fully eradicated since both of these creatures arrived. Unfortunately, the spread of their habitat only complicates the problem.

Dr. Stobo-Wilson and her peers noted that Australia’s 1.7 million foxes can be found in 80 percent of mainland territory, particularly in the continent’s forested southern regions. Naturally, cats are far more prevalent because of their status as charming pets. As a result, there are currently 6.6 million of them across Australia — covering 99.9 percent of the continent.

It’s no surprise that foxes prey on larger animals than cats and devour kangaroos, potoroos, and wallabies with ease. While cats tend to focus on smaller animals, however, they’re destroying far more species and eat five times as many reptiles, two-and-a-half times as many birds, and twice as many mammals as foxes.

“We need to deal with this problem of foxes and cats. People think that a couple of cats and foxes aren’t having an impact, but it adds up,” said Dr. Stobo-Wilson. “If we don’t do something about the predation pressure, we will lose more species.”

Unfortunately, animals like bettongs and quolls are targets of both predators alike. Co-author Sarah Legge, a wildlife ecologist at Australian National University, noted that “the poor buggers in the middle are getting a double whammy” of death as a result.

“Management of domestic cats is a huge issue,” John Read, an ecologist at the University of Adelaide, told the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. “Keeping cats contained helps prevent those environmental and health impacts and stops them getting out and breeding more feral cats.”

Diversity and DistributionsThe study’s authors are urging government officials to invest in more fenced enclosures and animal cullings.

Overall, the lack of stringent management of cats and foxes has seen species like the central rock rat driven to the brink of extinction. Legge has estimated that it only has 20 years left on the planet, provided thorough measures aren’t taken. The eastern barred bandicoot, meanwhile, currently only exists in fenced protection.

Ultimately, the dire warning issued by this study isn’t particularly new. Government officials announced plans to kill two million feral cats by airdropping poisonous sausage three years ago. However, this latest research is the first study to quantify just how much of an impact cats and foxes have made on the environment.

“In the last 10 years, Australia has lost three species of mammals,” said David Lindenmayer, an ecologist at Australian National University. “It’s not as if the rate of loss is slowing, in many cases that decline is increasing.”

Dr. Stobo-Wilson did note that measures such as fenced enclosures and culling have proven to be successful — but that more needs to be done. For her, these approaches must be ramped up, continent-wide, in order to produce any notable long-term effects. Ultimately, she and her peers put it rather plainly:

“Australia must drastically scale up the management of both predators, to give native wildlife a fighting chance and to help prevent future extinctions.”

After reading about Australian wildlife being threatened by cats and foxes, learn about the feral hogs wreaking havoc across Canada. Then, read about Australia losing one billion animals due to wildfires.