About 30 years ago, Canadian farmers released hogs into the wild as the meat market slowed. These pigs have since grown gigantic and are ravaging farmland across the continent.

Wikimedia CommonsThe feral pigs have been wallowing in stream beds — leading experts to worry about infectious diseases being spawned.

When Canadian farmers imported wild boars from Europe in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the goal was purely to raise meat.

Even though some of them escaped and others were freed once the meat market slowed, none of the farmers thought these animals would survive the harsh Canadian winters.

According to National Geographic, however, that was a mistake with hefty consequences, as descendants of those boars have since bred with domestic pigs — and are now wreaking environmental havoc on the country’s crops, wildlife, and grasslands.

Though unruly pigs might seem like a minor issue with a cartoonish level of threat, these feral hogs weigh up to 600 pounds and sport some seriously sharp tusks.

The wild and domestic traits they’ve inherited gave them both a tolerance for extreme cold and the ability to birth large litters.

They’ve even begun to build shelters above ground, since dubbed “pigloos” by experts. As such, wildlife researcher with the University of Saskatchewan Ryan Brook has decided to aptly dub this generation as “super pigs.”

“We should be worried, because we know the biology,” said Brook. “They’re called an ecological train wreck for a reason.”

This generation of hogs has been spotted from British Columbia and Manitoba. When they’re not harassing the regional livestock, they’re freely eating whatever they can get their tusks on. They’re also reproducing at an alarming rate.

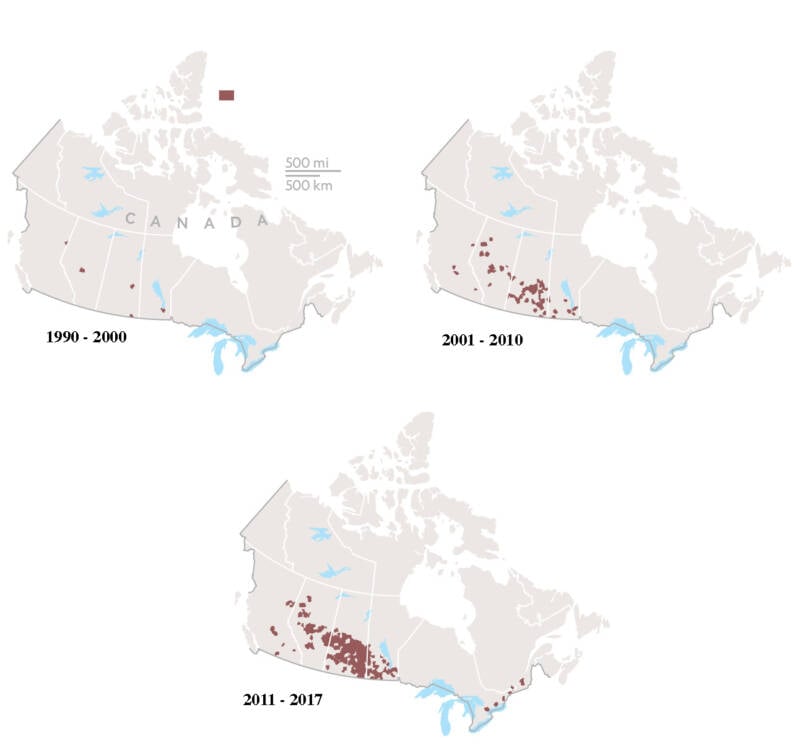

Doctoral candidate at the University of Saskatchewan Ruth Aschim says, “no one even knew where they were” until the last few years. Aschim and Brook, who serves as her adviser, spent three years mapping their spread using trail cameras, GPS collars, and interviewing local farmers and hunters.

Aschim practically lived out of her car for months, all the while meeting with biologists and conservation officers across Canada. Her findings, published in the Scientific Reports journal in May 2019, clarified the gravity of the issue for the first time.

Ruth A. Aschim/University of SaskatchewanFeral hog spread is correlated to watersheds — and has grown dramatically over the last 30 years.

The data generally showed that these hogs have covered tremendous ground in the last 30 years. They’ve even begun encroaching into new and unexpected territory, remarkably far away from where they were raised. All the while, they’re rummaging through private property.

“The rooting is really something to see,” said Alberta Agriculture and Forestry inspector Perry Abramenko. “It’s almost like a small backhoe has gone through some of these pastures.”

Unfortunately, it isn’t just farmland they’re destroying. These pigs are also wallowing in stream beds and potentially contaminating the waters. Experts are worried this could result in infectious diseases being spawned. The hogs also endanger motorists by suddenly crossing roads.

While feral pigs in the United States are generally found in warmer areas such as Florida, Texas, and California as a result of Spanish explorers introducing them in the 1500s, Canada is different.

“We have the exact opposite,” said Brooks. “The coldest spots — Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta, sort of north-central — is where we have, by far, the most pigs.”

While domestic pigs and European wild boars are both Sus scrofa, they are different subspecies and rarely interbreed.

Humans have raised domestic pigs for 10,000 years, with this variety being meatier and growing less hair. Commercial pig farming has also led them to reproduce more rapidly.

Descendants of escaped pigs, however, can quickly transform into their ancestral boar counterparts — growing longer coats and becoming feral. A February 2020 study comprised of data from 6,500 feral animals across America showed most feral pigs have a domestic ancestry.

Ryan BrookThe hogs cut down cattails with their teeth, making “pigloos” for warmth during the winter — and lie on top of them during the summer.

The hogs wreaking havoc in Canada, however, are more related to wild boars. They have litters of up to six piglets, twice per year, which is far more than Eurasian boars produce.

“If we had true Eurasian wild boar without any domestic pig, this whole issue would be a lot easier to handle,” said Brook. “Reproductive rates would be lower.”

These animals are using cattails to build “pigloos,” which capture a fair amount of heat on the colder days of the year.

“The cattails do a good job of catching the snow and it’s fairly thick and soft, so they can tunnel into that and have their little pigloos,” said Brook.

Perhaps most stunning is their size — Brook and his colleagues captured at least one hog that weighed more than 600 pounds. That’s a stark difference from the wild boars commonly found in Spain or the U.S. — which weigh on average between 150 and 200 pounds.

From the destruction of crops and grassland to the increasing risks these hogs pose to locals and their property, Brook adamantly opposes those who have yet to take this issue seriously. Everywhere they’ve spread, ruination has followed.

“Why would we expect anything except vast, dramatic ecological impacts?”

After learning about the huge feral hogs wreaking havoc across Canada, read about the 59-year-old Texas woman who was killed by feral hogs in her front yard. Then, learn about the feral pigs who ate and destroyed $22,000 worth of cocaine hidden in an Italian forest.