"It's incredible that in more than 250 million years of reptile evolution, the way the skull develops in the egg remains more or less the same. Goes to show — you don't mess with a good thing."

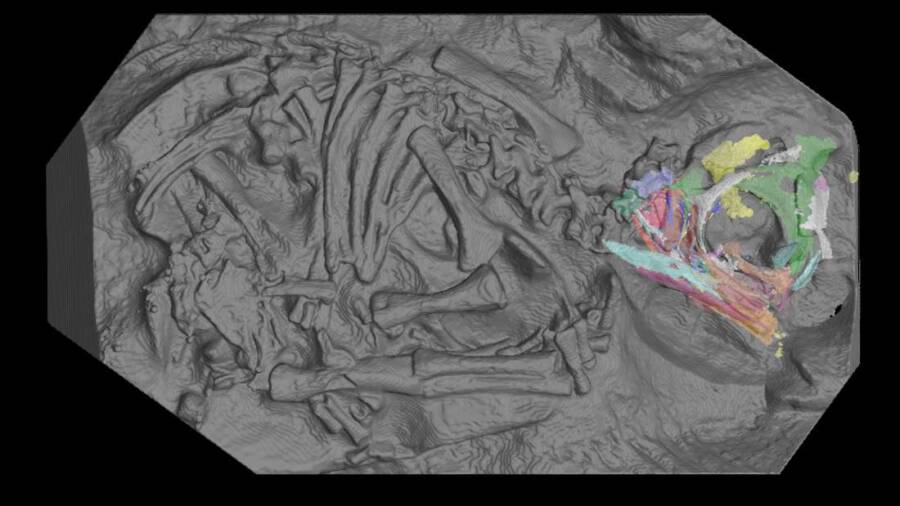

Kimberley ChapelleThis unprecedented image has allowed researchers to see inside dinosaur eggs like never before.

Scientists used a stadium-sized particle accelerator to scan 200-million-year-old dinosaur fossils — and then created 3D reconstructions of the skulls of baby dinosaur embryos.

According to IFL Science, the results of the remarkably detailed scans and 3D reproduction have offered unprecedented insight into how young dinosaurs developed.

The fossilized dinosaur eggs were discovered in South Africa’s Golden Gate Highlands National Park in 1976. The six-egg cluster contained fossilized embryos, which belonged to a bipedal herbivore species known as Massospondylus carinatus dating back 200 million years.

While this species grew as long as 16 feet, these embryos seem to have been fossilized at around two-thirds of their incubation period. They’re so tiny that the dinosaur skulls measured less than 0.8 inches long — with their teeth shorter than 0.04 inches.

Scientists were able to deduce that dinosaur embryo development was remarkably close to that of their living relatives, from crocodiles and lizards to turtles and chickens. According to Phys, these tiny embryos have historically proven fairly useless due to their fragility and size.

Brett EloffThe fossils in question are some of the oldest known dinosaur eggs and embryos ever discovered.

In 2015, however, Chapelle and colleague Jonah Choiniere transported their find to the French facility and managed to get them thoroughly scanned. The sophisticated process left researchers with nearly three years of data to process back at the university lab.

The international team of researchers used the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) in Grenoble to create the imagery. The installation’s 2,769-foot-long ring of electrons was accelerated near light speed — emitting such powerful X-ray beams that the scans showed individual bone cells.

“A synchrotron has several advantages over a laboratory CT scanner,” said Kimberley Chapelle, PhD, author of the study published in the Scientific Reports journal and vertebrate paleontologist at the University of the Witwatersrand in South Africa.

“For example, a synchrotron source is one hundred billion times brighter than a hospital X-ray source. Secondly, properties of the synchrotron radiation also make it thousands of times more sensitive to density contrast, meaning that it makes it much easier to differentiate bones from the encasing rock matrix.”

“No lab CT scanner in the world can generate these kinds of data,” explained Vincent Fernandez, co-author of the study and scientist at the Natural History Museum in London. “Only with a huge facility like the ESRF can we unlock the hidden potential of our most exciting fossils.”

Researchers were thrilled to find each embryo had two distinct sets of teeth.

One consisted of triangular teeth likely to be absorbed or shed before hatching — like the baby teeth of modern-day geckos or crocodiles. The other was similar to those of adult dinosaurs, likely the teeth they’d hatch with.

“I was really surprised to find that these embryos not only had teeth, but had two types of teeth,” said Chapelle. “The teeth are so tiny; they range from 0.4 to 0.7 mm wide. That’s smaller than the tip of a toothpick.”

As it stands, the team aims to use the same process on other dinosaur embryos to get an even clearer picture of their development.

Currently, the goal is to analyze the rest of this six-egg cluster — with the scanned arms and legs already proving that Massospondylus hatchlings walked on two legs.

“It’s incredible that in more than 250 million years of reptile evolution, the way the skull develops in the egg remains more or less the same,” said Choiniere. “Goes to show — you don’t mess with a good thing.”

After learning about these 200-million-year-old baby dinosaur embryo fossils, read about the Nodosaur dinosaur “mummy” discovered with its guts intact. Then, learn about the fossilized dinosaur-like “sea serpent” found with a baby in its belly.