The bloody story of the Battle of Blair Mountain, America's largest armed insurrection since the Civil War.

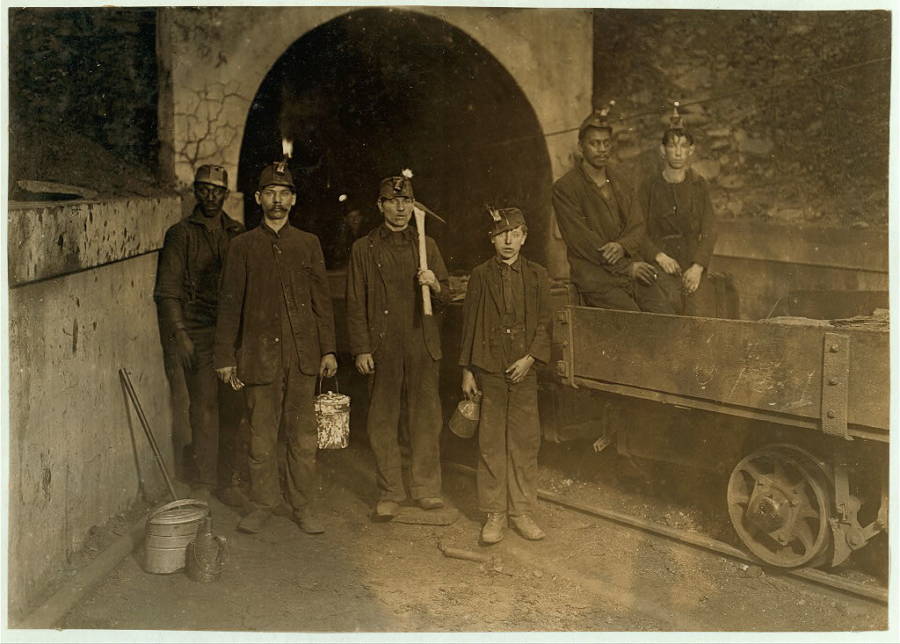

Lewis Hine/Library of CongressWorkers stand at the entrance to a West Virginia coal mine.

In February 2017, Fortune wrote about a viral Twitter prompt from sociologist Eve Ewing:

“If you could choose one historical struggle that many people don’t know about and have it be taught in schools, what would it be?”

Among dozens of “eye-opening” responses in this “crowdsourced curriculum,” Fortune identified The Battle of Blair Mountain, the largest domestic armed insurrection in the United States since the Civil War (and one waged in the heart of what some now call “Trump Country”).

If you’re unfamiliar with the 1921 conflict, you’re not alone. David Alan Corbin, author of Gun Thugs, Rednecks, and Radicals: A Documentary History of the West Virginia Mine Wars, writes that in “a dozen years of public schooling in West Virginia,” he heard “nothing” about the clash or its key figures, despite it being the largest labor uprising in American history and despite him being reared at its ground zero.

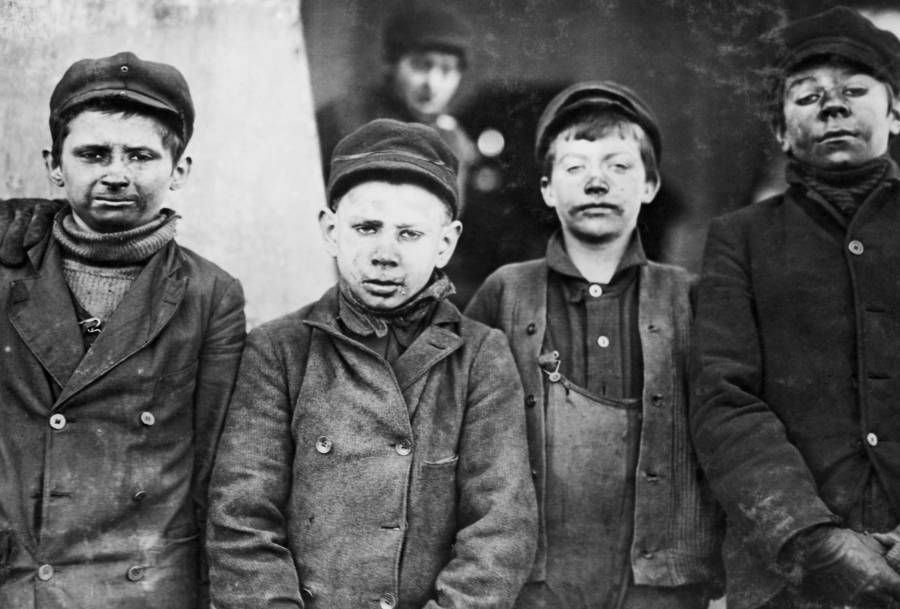

Lewis Hine/Bettmann/Getty ImagesWest Virginia boys stand near the coal mine in which they work.

At the ideological heart of this conflict that few have heard of was, as wSmithsonian rites, a battle between “collectivism and individualism, the rights of the worker and the rights of the owner.”

Specifically, the Battle of Blair Mountain was 10,000-15,000 West Virginian miners, many armed only with “squirrel-hunting rifles,” against 3,000 coal company supporters, including local police, federal troops, and even a U.S. army bomber (“the only time in history that U.S. air power has been used against American civilians,” according to NPR).

What set off such an unprecedentedly messy domestic conflict?

Simply put, the miners, facing life-threatening conditions on the best of days, wanted better treatment from the coal companies. Smithsonian elaborates:

“The coal industry was essentially the state’s sole source of work, and massive corporations built homes, general stores, schools, churches and recreational facilities in the remote towns near the mines. For miners, the system resembled something like feudalism. Sanitary and living conditions in the company houses were abysmal, wages were low, and state politicians supported wealthy coal company owners rather than miners.”

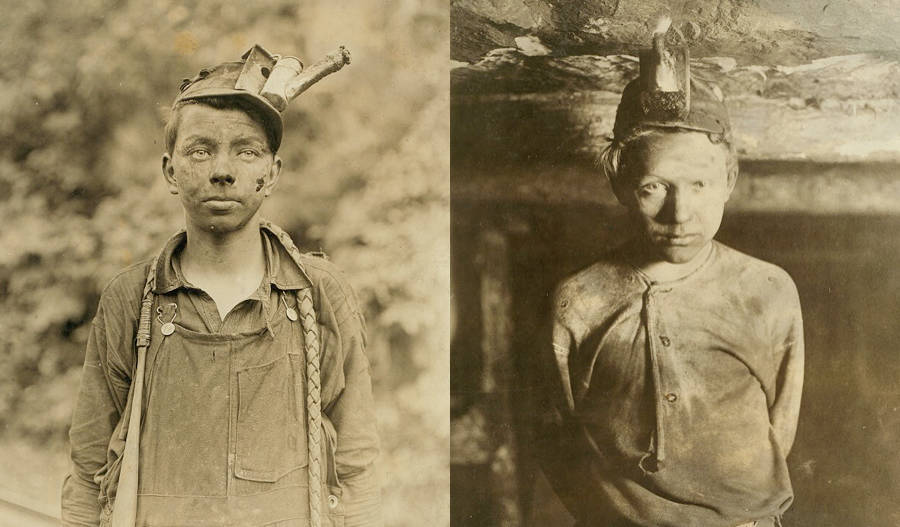

Lewis Hine/Library of CongressTwo West Virginia boys at work in the coal mines.

Doug Estepp, a local historian who runs tours of the area, told NPR in 2011 that some of the companies had contracts prohibiting and punishing miners trying to organize into the fledgling unions:

“They had the yellow-dog contract which said that, basically, if you took a job at this mine, you could not associate with anyone in the union, you couldn’t join. You were basically fired, blacklisted and evicted — and probably beaten on the way out by the guards just for good measure.”

In the years leading up to the Battle of Blair Mountain, strikes and attempts to unionize were also thwarted by the Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency, a private firm hired by the mining companies to keep workers in line.

Don’t let the quaint-sounding “Detective Agency” title fool you. Agents were armed with machine guns, Tommy guns, and high-powered rifles, and were known to sweep through strike camps in an armored vehicle known as the “Death Special,” firing on miners and their families. One mother of three later told government officials about one particularly harrowing incident:

“Mrs. Annie Hall, who limped into the committee room, told the committee how she shielded her three little children from the bullets by hiding them in the chimney corner of her home at Holly Grove when the armored train made its appearance. She said she had been shot through the feet by a bullet which passed through the Bible and hymnal on her parlor table.”

In 1920, this violence begat more violence, and triggered a conflict that ultimately left behind a battlefield as “big and extensive as maybe a World War I battlefield,” according to Kenny King, a prospector, “amateur archaeologist,” and local expert on the Battle of Blair Mountain.

A gunfight in the spring of that year between Baldwin-Felts agents and a pro-union group, including Matewan, West Virginia’s police chief, ended with 10 dead, including the town’s mayor. Less than a year later, after the chief was acquitted by a local jury, Baldwin-Felts agents gunned down both him and his deputy on the courthouse steps.

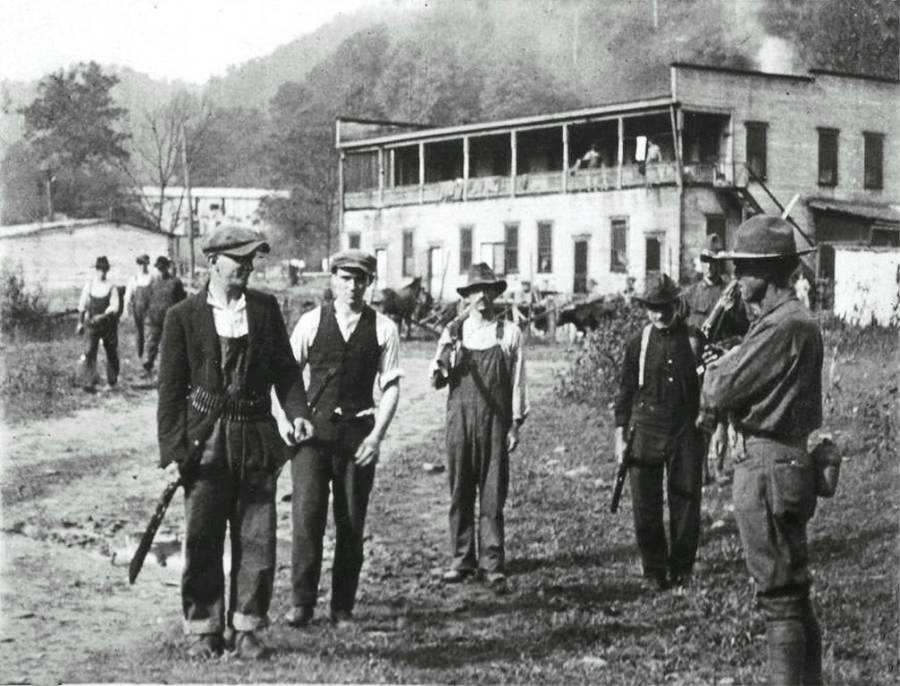

Libcom

This blatant assassination fueled the fire, rallying 10,000-plus miners to wage war on the agents, the coal company, and, when President Harding saw the need, federal troops with leftover World War I munitions. For more than a week, the area felt like a relentless war zone to area residents, according to James Green, author of The Devil Is Here in These Hills: West Virginia’s Coal Miners and Their Battle for Freedom:

“The local doctor, an army veteran, said he heard about as much shooting that day as he had when American forces assaulted Manila in the Philippines during the Spanish-American War. And some of the miners told reporters how much the fighting on Blair Mountain resembled the furious woodland combat they waged against the Germans in the dense Argonne Forest of France.”

Wikimedia CommonsSeveral miners pose with a bomb that had been dropped on them during the Battle of Blair Mountain.

When the smoke cleared on the Battle of Blair Mountain, an estimated 1 million rounds were fired, dozens were killed, and 985 miners were arrested. The uprising was suppressed, but public awareness about the appalling conditions in which the miners were forced to live, work, and raise their families grew considerably.

Wikimedia CommonsSheriff’s deputies fight during the Battle of Blair Mountain.

Nevertheless, it wasn’t until the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933 that the southern West Virginia coalfields were allowed to be properly unionized, with miners bargaining collectively for better conditions without fear of persecution — or execution. In the years that followed, according to Jacobin, the number of mining-related deaths fell by one-third.

With all the talk in recent years of the coal industry, its place in U.S. history, and the pros and cons of its revival, learning how miners in West Virginia fought for the still-not-great working conditions they have today is critical if you want to understand class conflict in the United States.

Ideally, awareness of the Battle of Blair Mountain and the West Virginia Mine Wars will guard against warping its narrative into an “alternative history,” built on “alternative facts,” a history that masks how the working class has always had to agitate, sometimes successfully, against appalling and sometimes lethal working conditions — and those in power who conspire to foster them.

After this look at the Battle of Blair Mountain and the West Virginia Mine Wars, discover the bloody history of labor unions in the United States. Then, have a look at Lewis Hine’s most haunting early 20th century child labor photos.