A 2018 study determined that there were 93 penises depicted in the 11th-century Bayeux Tapestry — but now one scholar claims he's found a 94th.

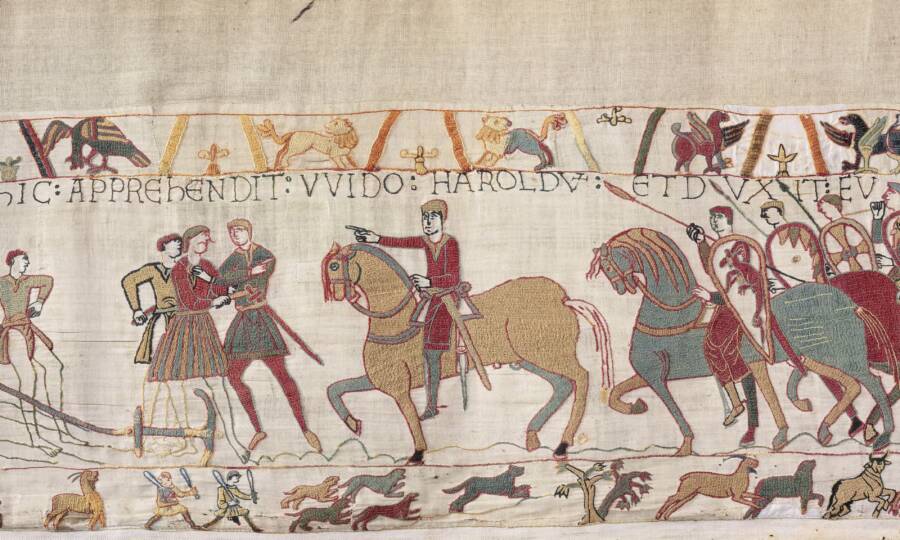

Bayeux MuseumThe figure on the bottom right is the subject of the debate, as scholars cannot determine whether he has a penis or scabbard.

Scholars are currently locked in a heated debate over the number of penises depicted in the Bayeux Tapestry. In 2018, University of Oxford’s Professor George Garnett counted 93 individual genitalia on the 11th-century embroidery, with 88 belonging to horses and five to human men.

Now, Bayeux Tapestry expert Dr. Christopher Monk claims he’s found a 94th penis. Garrett disagrees with Monk’s assessment, however, and insists that the alleged genitalia is nothing more than the scabbard of a sword or dagger.

Other scholars are also weighing in, bringing unexpected attention to this 1,000-year-old work of art.

What Is The Bayeux Tapestry?

The Bayeux Tapestry is a sprawling piece of embroidery that depicts the 11th-century Norman conquest of England. The linen cloth is roughly 230 feet long and 20 inches high, and it was likely created in the 1070s, shortly after William the Conqueror’s forces defeated those of Harold Godwinson, the last Anglo-Saxon king of England.

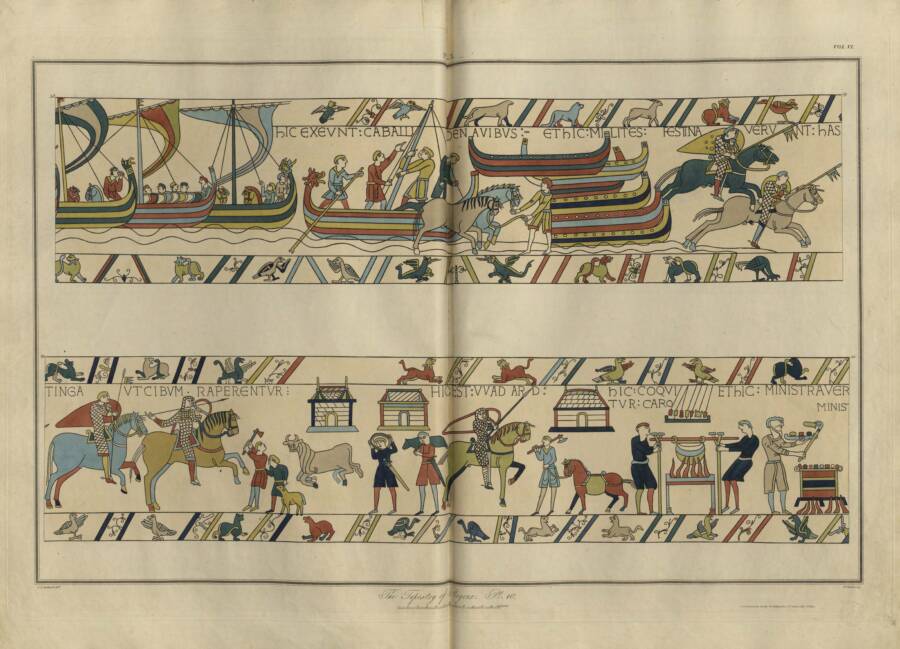

Bayeux MuseumThe Bayeux Tapestry tells the tale of the Norman conquest and features many literary allusions in the borders.

Historians suspect that it was commissioned by Bishop Odo of Bayeux, William the Conquerer’s half-brother, and embroidered by Anglo-Saxon artists. For much of its history, it was held in Bayeux Cathedral and displayed annually. Today, it is housed in the Musée de la Tapisserie de Bayeux in Bayeux, France, with a 19th-century replica on display at England’s Reading Museum.

Interestingly, many of the penises depicted in the original tapestry were not transferred over to the Victorian recreation, as the Leek Embroidery Society, which made the replica, was given censored etchings, engravings, and photos to work from.

Public DomainEngravings made in the 19th century by Charles Stothard during the restoration of the tapestry.

When Professor George Garnett carried out his 2018 examination of the penises on the tapestry, he naturally worked from the original embroidery. He concluded that there were 93 penises in all — and after he published the results, the research quickly went viral and sparked conversation among his peers.

“I think my academic colleagues were mostly very entertained,” he told the HistoryExtra podcast in a 2025 follow-up interview. “One of them said to me, ‘You’re not a historian of masculinity; you’re a historian of masculinities, 93 of them.'”

However, a recent re-examination of the Bayeux Tapestry by fellow historian Dr. Christopher Monk challenges Garnett’s findings — by one single penis.

Inside The Debate Over The Number Of Penises On The Bayeux Tapestry

When Garnett carried out his examination, he determined that any visible human genitals in the tapestry were all connected to nude figures. However, Monk noticed one man on the tapestry who was clothed — but had something hanging from the bottom of his tunic. Garnett saw this during his studies, too, but he remains certain that it is meant to be a scabbard, not a penis.

Monk, however, said, “I am in no doubt that the appendage is a depiction of male genitalia — the missed penis, shall we say? The detail is surprisingly anatomically fulsome.”

So, why does this matter? Scholars believe that whoever designed the tapestry was an educated person, so the genitalia likely weren’t added for comical or smutty reasons. Rather, the penises were meant to make a point.

Bayeux MuseumAnother scene from the Bayeux Tapestry, featuring a nude male and female in the bottom border.

“Sexual activity is involved, or shame, and that makes me think that the designer is covertly alluding to betrayal,” Garnett said. “What’s fascinating is that everybody who saw the tapestry at the time must have known exactly what was being referred to. But we don’t.”

Admittedly, Garnett said that it would have required a learned mind to pick up on these allusions at the time — and that perhaps the designer didn’t care if others got the point. Maybe he was simply smugly prideful of his own cleverness. In either case, Garnett said his fascination with the tapestry is reflective of a deeper fascination with understanding medieval minds.

“The whole point of studying history is to understand how people thought in the past,” he said. “And medieval people were not crude, unsophisticated, dim-witted individuals… The designer was an intelligent, highly educated individual, using literary allusions to subvert the standard story of the Norman conquest.”

Monk also spent a great deal of time exploring nudity in the tapestry, even writing a book chapter on the subject in 2016. He had previously spent “several years looking closely at depictions of nakedness in Anglo-Saxon manuscripts” as part of his doctoral research.

Bayeux MuseumA closer detail of the figure at the center of the debate.

Monk consulted with medieval embroidery expert Dr. Alexandra Makin to determine if any restoration work had been done on this clothed man’s penis (or scabbard) in particular. “I knew there was some restoration in places,” Monk said. “Alex had studied the back of the tapestry and taken photographs, so was in a position to use her expertise in answering my queries.”

After hearing back from Makin and reading the restoration notes of the 19th-century antiquarian draftsman Charles Stothard, Monk felt he had found sufficient evidence that restoration work had indeed been performed on the penis. He noted that “some of the stitches appeared to be original: the pale thread of the circular testicles and possibly the tip, or glans, are so; the black stitches of the shaft are, though, later restoration.”

If Monk is correct, it could be that restoration converted what had once been a penis into a more scabbard-like object, though the reason for doing so remains unclear. Of course, there’s always the chance that Monk is incorrect, and Garnett’s initial count of 93 penises was accurate. In either case, this research has put the Bayeux Tapestry — and Professor Garnett — back in the spotlight.

“My sons were ecstatic at the latest abuse heaped upon me online,” Garnett said. “Someone wrote, ‘If only he’d looked in a mirror, he would have seen a 94th!'”

After reading about this debate surrounding the number of penises on the Bayeux Tapestry, go inside the many myths and legends about Rasputin’s penis. Then, read about the strange journey of Napoleon’s penis after his death.