"Better Babies" contests scored children on a 1,000-point scale that was generated based on the racist principles of eugenics.

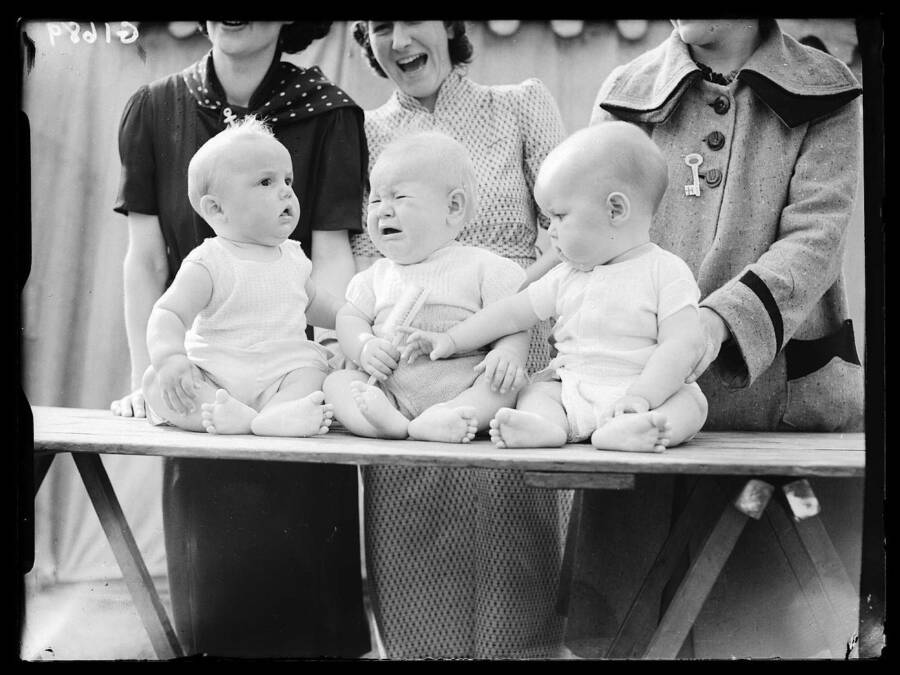

Reuben Saidman/National Media MuseumBabies aligned at a 1938 Better Babies competition.

In the early 20th century, visitors flocked to state fairs to gawk at prize-winning livestock, enormous vegetables, delicious pies — and babies.

At these so-called Better Babies contests, judges examined and rated infants based on their physical and mental health. Then, they awarded the parents of those babies they deemed to be the fittest.

These contests were in part meant to promote better health and hygiene habits in new parents, but the competitions also had a dark side: they were driven by the racist principles of eugenics. As these contests became more popular, they would go beyond judging babies to judging entire families.

How Better Babies Contests Worked

In 1908, the Louisiana State Fair held the first Better Babies contest.

As a 1913 article described the competitions: “A physician scores a baby in precisely the same way as a judge of experience in livestock scores cattle…It is first necessary to establish a standard and then to compare each entry or specimen with what is known as a one-hundred percent, or perfect, product.”

Infants were lined up for judging and then nurses and doctors inspected each child and recorded their measurements, which included the child’s weight, chest circumference, and mental capacity. Babies who were too shy to engage in interactive tests would lose points.

The judges scored babies on a 1,000-point scale, with 700 points for physical appearance, 200 points for mental and psychological fitness, and 100 points for physical measurements.

The winners, or the most “scientific” babies, received silver trophies.

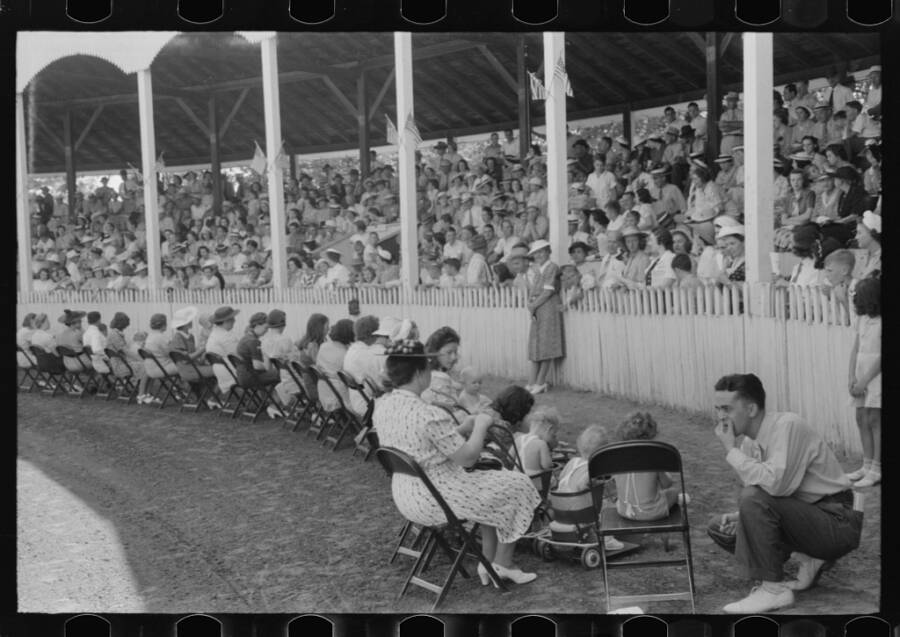

Marion Post Wolcott/Library of CongressPictured is a Better Babies contest at the Shelby County Fair and Horse Show.

The Better Babies fad was started by a nurse named Mary DeGarmo who was an advocate for child welfare. DeGarmo wanted to promote health and hygiene in the childrearing process and so she worked with a Louisiana doctor to develop a scorecard that mothers could use to measure their own success at raising their child.

The idea caught on and quickly spread. In the 1910s, the magazine Woman’s Home Companion published a national scorecard and even created a bureau to promote the competitions.

But even as Woman’s Home Companion stated: “Underneath the inviting charm of the idea is a serious scientific purpose — healthy babies, standardized babies, and always, year after year, Better Babies.”

The State Of Child Welfare In The Early 20th Century

Marion Post Wolcott/Library of CongressA father shows off his prize-winning baby at a Kentucky county fair.

The Better Babies contests did address a larger problem in national health at the time, even if the methods behind them were nefarious. In the early 20th century, infant mortality rates were still high in the U.S. One child in 100 died before their first birthday.

Healthcare professionals and public health officials struggled to find ways to improve the health of children and many citizens followed suit by jumping on this newfound cause of “baby saving.”

In an era before routine wellness screenings and physicals, Better Babies contests gave doctors and nurses the opportunity to assess child welfare and physical development across the country.

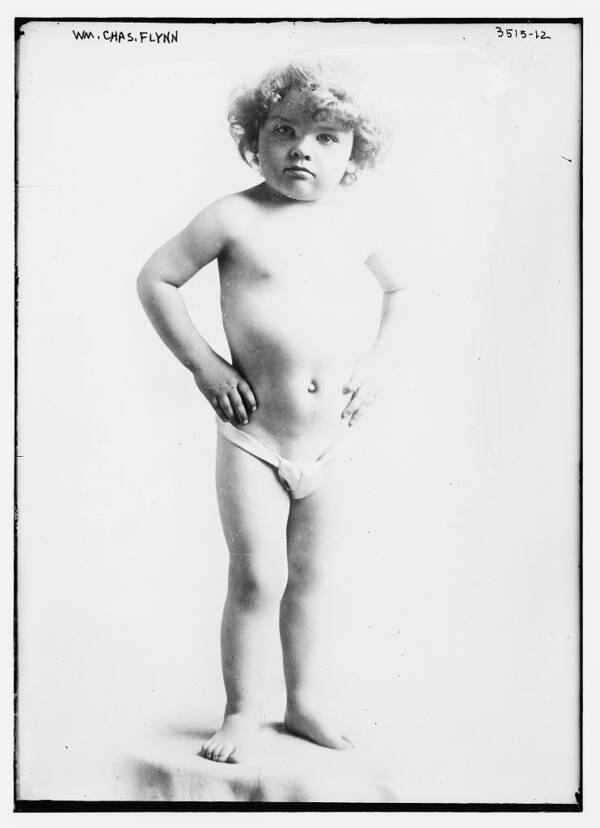

Bain News Service/Library of CongressWilliam Charles Flynn, the winner of a Better Babies contest.

At early competitions, the parents of babies who earned poor scores were sent home with pamphlets that promoted the health of their infants. Also during this time, only children between six months and four years old could enter the contests. But soon, competitions began to include older children — and even adults.

Mary DeGarmo believed that the contests revealed a baby’s, and therefor its family’s, genetic fitness. As she explained: “Much interest was shown as to the ‘Blood Will Tell’ theory. IT DID TELL.”

Indeed, DeGarmo thought that in encouraging fitness and rewarding the “right” parents or those who followed her advice, then the country’s genetic stock would improve.

The Bigotted Ideas Behind Better Babies Contests

George Rinhart/Corbis via Getty ImagesA staff of 40 or more nurses and doctors had to examine 983 children between the ages of two months and five years for a Better babies Contest.

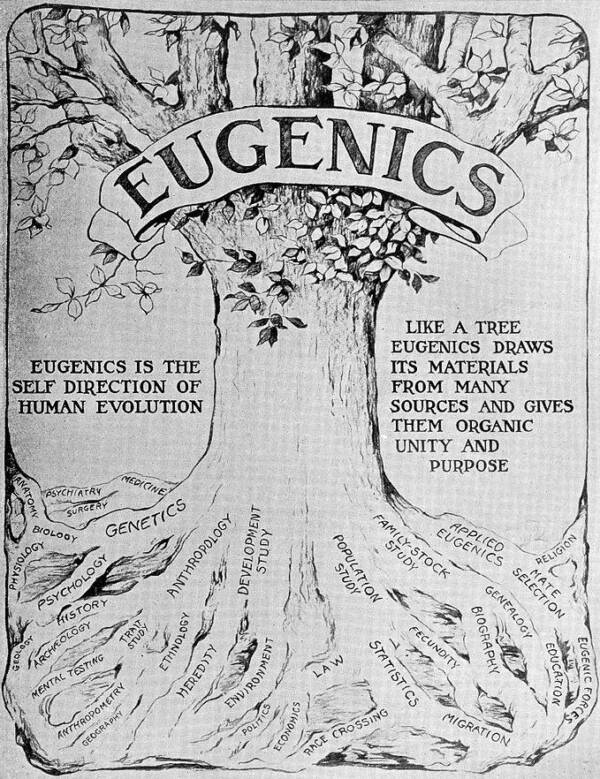

Eugenicists believed that humans could improve their offspring through selective breeding, much like breeding livestock or purebred dogs. The movement gained popularity in early 20th-century America when many Americans had developed xenophobia in response to increased industrialization and immigration.

The desire to produce a better generation of humans may have been noble, but in practice, the theory was largely borne out of racist and colonialist ideologies. White researchers claimed that “lesser” races needed to be bred out to ensure that white people (and their genes) remained untainted.

Because eugenicists believed people inherited traits like feeble-mindedness and poverty, this meant that society had an obligation to thin this herd. Unfortunately, many impoverished, malnourished, and uneducated Americans at this time were people of color and new immigrants.

Naturally, it followed for eugenicists that the perfect human was white and that white, well-educated, wealthy people should continue to breed.

Even some of our nation’s most renowned thinkers were outspoken eugenicists, including Helen Keller and Theodore Roosevelt. Indeed, President Theodore Roosevelt even once lamented that the U.S. “permits unlimited breeding from the worst stocks.”

Third International Congress of Eugenics/Wellcome ImagesA wall panel at the Third International Congress of Eugenics showing the relationship between eugenics and other sciences.

This desire to generate a “better” race of people instigated the Better Babies competitions, where the “right” (or white) families were rewarded for having children. Eugenicists linked physical appearance, intelligence, and even personality to genes, claiming that these contests measured genetic health.

And so, even though the contests claimed to generate an unbiased score for each child and promoted the health of infants the nation over, they actually just rewarded babies that fit their society’s definition of superiority: middle-class, rural, and above all, white.

DeGarmo saw both nature and nurture as key ingredients in a child’s health. She asserted that “child hygiene result[ed] from proper inheritance, as well as food and clothing and environment.”

Enter, The “Fitter Families” Movement

Better Babies contests became so popular that entire families wanted to join in the competition. In 1920, Kansas debuted the “Fitter Families” competition where families would present their entire lineage to prove their overall fitness.

According to the Emporia Gazette, these competitions would “apply the well-known principles of heredity and scientific care which have revolutionized agriculture and stock-breeding in the next higher order of creation – the human family.”

Unknown/Wellcome ImagesFamilies gather for a Better Babies contest.

Another Kansas newspaper expanded on that point: “The people of this progressive state no longer are content to breed only better animals. They are setting out to raise better citizens: to apply to the human race, some of the principles of heredity which have worked wonders in livestock improvement.”

State fairs did more than hold competitions, though. They also hosted eugenics booths where visitors could learn about the principles of selective breeding and learn how to apply these lessons to their own lives. These exhibits even told unmarried fairgoers how to choose genetically fit spouses to ensure desirable traits in their children.

The Impact Of Better Babies Contests

All told, the Better Babies contests did more than rank children. Because the definition of fitness in these babies was inseparable from the idea that healthy white Americans were superior to others because of their genes, these contests only legitimized and rewarded a bigoted ideology.

The scorecard simply reflected what a racist faction of society deemed desirable.

Minnesota Historical Society/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty ImagesMothers and infants gather on the stoop of the Cathedral of St. Paul for a Better Babies contest.

The ideas behind these contests were also used to justify discrimination on the federal level. Indeed, in the 1924 Immigration Act, the U.S. strongly limited who was allowed to enter the country based on the principles of eugenics. As President Calvin Coolidge declared, “America must remain American.”

Three years later, the Supreme Court mandated that the government was allowed to sterilize anyone deemed “unfit.” This included a poor unwed mother who was declared “feeble-minded” after she was raped. The government claimed that it had an interest in preventing “unfit” children from burdening the welfare system, and so they gave states the power to regulate reproduction.

In the end, Better Babies contests were driven by the same bigotted ideology that created racist policies like these in early 20th-century America.

The Better Babies contests were only one part of the eugenics movement in America. Learn more about the American eugenics programs that inspired Nazi Germany and then check out pictures from the heyday of eugenics.