Bobby Sands was a member of the Irish Republican Army and spent the last 66 days of his life on hunger strike in HM Prison Maze fighting for political prisoner status.

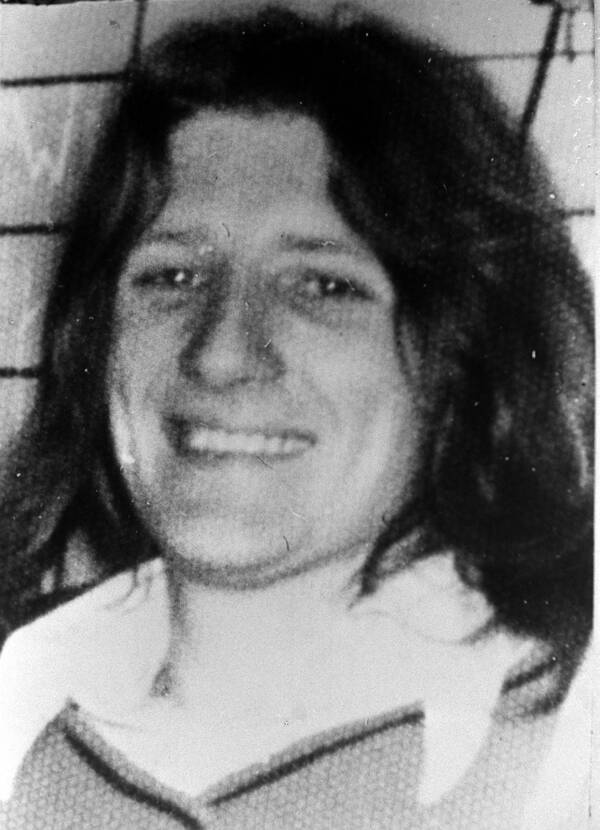

PA Images via Getty ImagesBobby Sands, who died on hunger strike in 1981 at the age of 27.

Bobby Sands’ earliest memories were of the Troubles, the thirty-year period in which rival armed factions vied with one another for control of the six counties of Northern Ireland. And so too would be his last.

As an adult, a decade of service with the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) led him to a dank prison cell and direct confrontation with the British government in 1981. IRA prisoners were once classified as political prisoners with rights beyond those afforded to common criminals, but by 1976, that special category had been revoked.

As the leader of the IRA members imprisoned in the H-Blocks of Her Majesty’s Prison Maze, then called Long Kesh Detention Center, it fell to Sands to continue their struggle for that status back and demand better treatment from guards and by the British government.

After a series of escalating protests that captured public attention, Sands and his followers staged a final, fatal hunger strike that would change the course of Irish history.

Bobby Sands’ Childhood Amid The Troubles

Michel Philippot/Sygma/Sygma via Getty ImagesBobby Sands’ childhood was dominated by the eruption of sectarian violence in his native Belfast.

Robert Gerard Sands was born to a Catholic family in Belfast in 1954. Catholics had made up a substantial and often disadvantaged portion of Northern Ireland since the country was formed in 1922, when the southern counties gained independence as the Irish Free State.

In 1922, Northern Ireland’s first prime minister, James Craig, described his government as “a Protestant parliament and a Protestant state.” Protestants, or “loyalists,” controlled the police and many industries, and they held significant social power over working-class Catholics.

Intense religious and ethnic strife had followed the division, with tensions especially high in Northern Irish cities like Belfast and Derry. Although Bobby Sands was born in a relatively mixed neighborhood, his family had to move early on due to harassment and intimidation, eventually settling in Rathcoole, which was about 30 percent Catholic in the early 1960s.

But by 1966, tensions came to a head. That year marked the 50th anniversary of both the Battle of the Somme, where thousands of Irish Protestant soldiers had died, and the Easter Rising, when Irish independence fighters staged a failed revolt against Britain. The Protestant Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) attacked Catholics who paid homage to the Rising, killing several.

Suddenly, Sands’s Protestant friends wouldn’t speak to him, and he found it easier to associate exclusively with other Catholics. And by 1969, he had dropped out of school to go to work.

Joining The IRA

Wikimedia Commons/The National ArchivesPrime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s hardline stance against the IRA led to increased friction in Northern Ireland, where Catholics largely sympathized with Bobby Sands and other men on the H-block.

By the time Bobby Sands was working as an apprentice bus-builder at 16, tensions had reached a breaking point. Teenaged “tartan gangs” roamed Belfast’s streets to target Catholics.

Sands arrived at work one morning in January 1971 to find Protestant co-workers cleaning guns, who told him, “Do you see these here? Well, if you don’t go, you’ll get this.”

Over the next year and a half, Sands’s family endured loyalist attacks on their home and were finally driven from Rathcoole by June 1972. They relocated to the Twinbrook estate in nationalist West Belfast. At that point, Sands decided militancy was the only option. He joined the IRA that same month.

Sands immediately dedicated himself to the new cause. He organized a unit of teenagers in Twinbrook and eagerly took part in securing money, weapons, vehicles, and recruits. A fellow IRA member later said that Sands “was always the first to say, ‘I’ll do that!’ He had to have a hand in everything.”

Gradually, the IRA became Bobby Sands’ full-time vocation. He later claimed that “my life… centred around sleepless nights and stand-bys. Dodging the Brits and calming the nerves to go out on operations.”

Political Awakening In HMP Maze

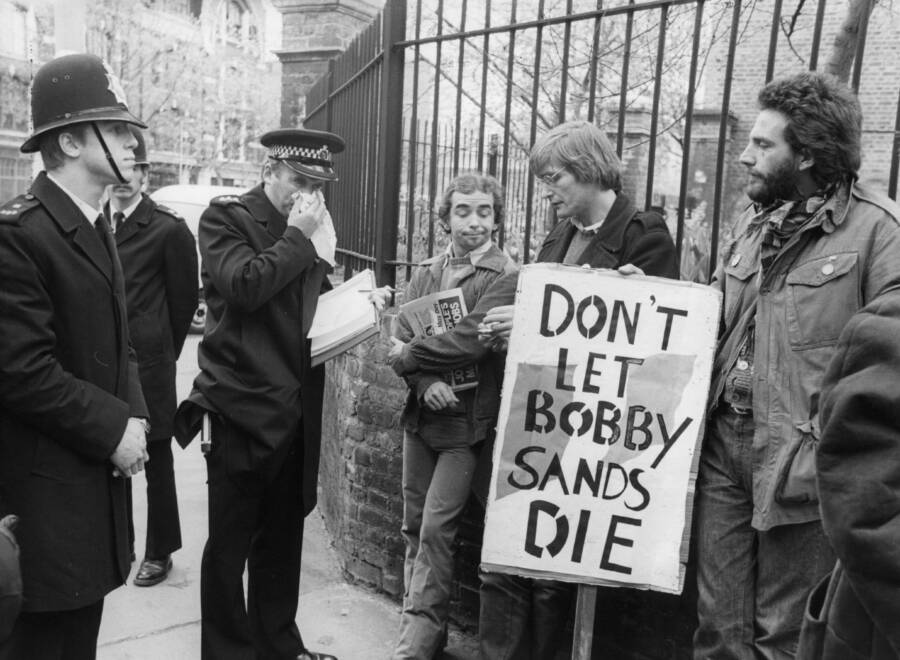

Central Press/Getty ImagesThroughout Europe, thousands of protesters urged the British government to give in to Sands’ demands.

In reality, Bobby Sands and his unit never carried out any direct action against the police or British Army patrols. Their only weapons were a collection of aging pistols that couldn’t fire, and their attempts to manufacture bombs met with failure. Much of 1972, he spent securing funding, mainly through robbery.

When a neighbor who looked after his unit’s faulty weapons lost her nerve and reported them to the authorities, Sands went on the run for a few days before he was caught and interrogated. He readily admitted to a string of robberies and the possession of the firearms.

He was sentenced to three years in HM Prison Maze, some of which was also spent in Crumlin Road Gaol, Belfast. While in prison, he participated in riots against heavy-handed treatment from the guards and slowly developed his political thinking, wondering how to turn the prisoners’ ordeal into an effective media campaign.

Among his fellow inmates was Gerry Adams, later the leader of the IRA’s political party, Sinn Féin, who encouraged the younger man to think in radical new ways.

Sands was released in April 1976 but was arrested again in 1977 on further weapons charges that resulted from a bombing and gun battle with the Royal Ulster Constabulary at the Balmoral Furniture Company in Dunmurry.

In the meantime, the British government had announced that IRA prisoners involved in the Troubles would no longer receive special political status, effectively turning them from prisoners of war to common criminals. This meant that they would be required to wear prison uniforms, do prison labor, and lose guarantees to conjugal visits and care packages.

In response, Sands and other IRA prisoners protested by wearing nothing but blankets rather than don prison clothing. The “blanket protest” was met with brutality, and Sands and others were frequently beaten in attempts to force them to submit.

Two years later, the blanket protest evolved into the “no-wash” or “dirty protest,” in which prisoners refused to wash or empty chamber pots. By intentionally degrading their health and their conditions, the prisoners weaponized what little power they had left.

Bobby Sands’ Hunger Strike

Jacob Sutton/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images)After months of hunger striking, Bobby Sands and nine others died, stirring sympathy and outrage across the world.

The dirty protest carried on with no sign of either side letting up for two years. But when Tomás Ó Fiaich, a Catholic archbishop, visited the prison and publicly condemned what he saw there, a media explosion ensued. Journalists began regularly visiting and interviewing the prisoners, turning what had been an invisible contest into a public struggle.

To capitalize on the new attention, Bobby Sands and other senior IRA prisoners formed the Anti H-Block political faction. They decided that the most visible way to gain support was through a hunger strike. These had been carried out before in the prison, but only by individuals and for specific demands. What they were now planning was to dwarf all their earlier efforts.

Prisoners would take it in turns to refuse food for as long as they could, at which point another group would take over for them. The first strike consisted of seven men, who held out for 53 days. But it was called off before anyone died.

But Bobby Sands’ hunger strike would be different. He was prepared to die. And on February 28, 1981, he ate his last meal. The next day, he began a 66-day hunger strike which forced a confrontation with British leader Margaret Thatcher herself, who refused to give in.

“We are not prepared to consider special category status for certain groups of people serving sentences for crime,” she said. “Crime is crime is crime, it is not political.”

To offer Sands’ campaign greater political legitimacy in response to Thatcher’s stance, his sympathisers on the outside had him elected to Parliament when a seat opened up.

But he never managed to take up the seat. Less than a month after his election, Sands died of starvation on May 5, 1981, at the age of 27. Nine other hunger strikers would also succumb before the strike was finally called off on October 3.

How Bobby Sands’ Hunger Strike Fueled The Troubles

Wikimedia CommonsAfter his death, Bobby Sands’ image became a common subject for pro-IRA murals in Northern Ireland.

More than 70,000 people lined the route between the Sands family house and St. Luke’s Chapel where Bobby Sands’ funeral was to be held. The procession was accompanied by an IRA guard of honor, who placed an Irish tricolor flag, black beret, and gloves on top of the coffin.

The deaths of the 10 hunger strikers transformed the image of the IRA in the public imagination. Instead of just another armed faction, they were increasingly seen as a legitimate popular political movement by Catholics.

Statements of sympathy were issued by a variety of activists and politicians throughout Europe and the world, and protests were held against the continued British presence in Northern Ireland.

The IRA saw a surge in membership and activity, and there were days of riots in Belfast that May. Britain passed a law banning long-term prisoners from standing in elections, and Northern Irish authorities at last dropped the requirement for political prisoners to wear prison uniforms.

And 17 years later, Gerry Adams played a key role in negotiating the Good Friday Agreement, which finally brought about a lasting ceasefire in 1998. Yet the division between North and South, Protestant and Catholic, remains to this day, a full century after the island was torn in two.

After learning about Bobby Sands’ momentous protest, have a look at these striking images of thirty long years of the Troubles. Then, read about the 1972 Bloody Sunday massacre, one of the most tragic instances of violence in modern Irish history.