Camille Claudel's talent as an artist was ultimately overshadowed by her troubled affair and increasing paranoia.

Wikimedia CommonsCamille Claudel, circa 1884.

Tumultuous affairs, promiscuous work, psychiatric hospitals, family problems. French sculptor Camille Claudel went through all of it. But she wasn’t simply a manic artist.

Considered a genius by contemporaries, Claudel was trying to be an artist during a time when women weren’t considered artists. Her struggle led to her mental decline, ultimately ending up in an asylum. After smashing most of her work to pieces and being admitted, she never created art again. Her talents only became widely known years after her death.

Camille Claudel Takes Shape As A Sculptor

Born into a rich family in 1864, Camille Claudel fell in love with art at an early age, despite it being a male-dominated field. While her father approved of her passion, her brother and mother did not.

By the time she was a teenager, she was already a talented sculptor and attended classes at the Academie Colarossi in Paris, one of the few art schools that accepted women. In 1882, following her studies, she rented a studio and shared it with several other female artists including Jessie Lipscomb.

The two women embarked on daring art careers together. Claudel explored sexuality in her work, which wasn’t unacceptable in itself. It was that she was encroaching on men’s territory; at the time, expressing lust in art was exclusively reserved for men.

Claudel stayed with Lipscomb’s family for holidays, as her own mother disapproved of her work. However, the two eventually had a falling out, a pattern that would continue with many people close to Claudel.

Still, Camille Claudel’s talent didn’t go unnoticed. Her father sent her work to Alfred Boucher, a renowned French sculptor, who was so taken with her work that he became her mentor.

Meeting Rodin, An Affair Begins

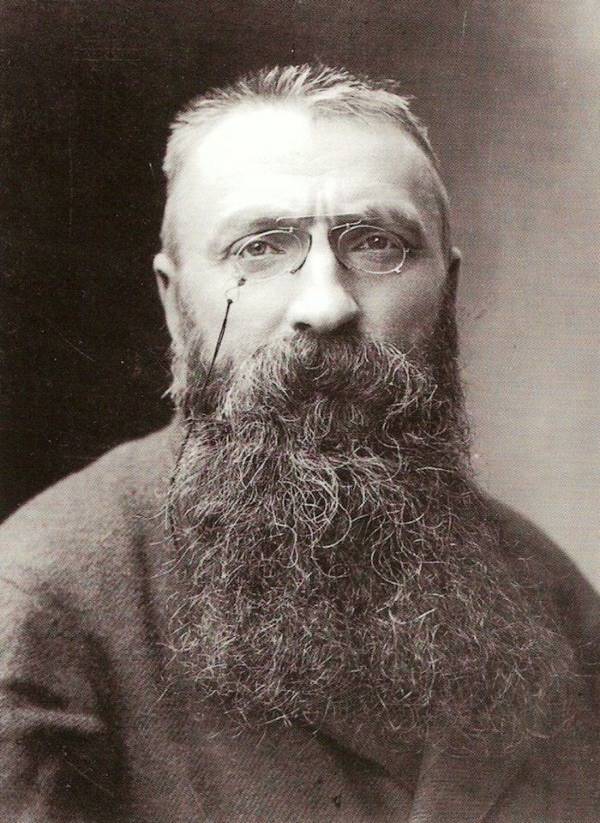

Wikimedia CommonsAuguste Rodin in 1891.

Through Boucher, around 1884, Camille Claudel met fellow sculptor Auguste Rodin.

Rodin was impressed with the realism in her work right away. He needed help around his workshop, and as an intelligent woman, she filled the role while also becoming a confidant for him. She learned from him in the process, developing skills like carving marble.

Then he fell in love with her. He was 24 years older and had been in a two-decade-long relationship with a woman named Rose Beuret who he refused to leave. Nonetheless, the two sculptors began an affair.

Though it lasted two years, the romance was a tumultuous one filled with intense arguments. Claudel’s upper-class family even cut her off because of it, and she had at least one abortion during its course.

For Rodin, Claudel’s ability to understand him on a deep level made him happy, but she was more ambivalent. Her family had disregarded her, and her father (the only one who supported her art career) had died. Since it was difficult for women to get commissions, especially so for Claudel because of the sexual nature of her work, she became financially dependant on Rodin.

Claudel also needed Rodin to have her work shown and bought. Several of her pieces were purchased by French museums with the help of Leon Gauchez, who was a respected Belgian art dealer and a friend of Rodin’s.

For a large part of her career, Claudel was in the shadow of Rodin as her work was constantly compared to his. She also had to collaborate with him on her pieces much of time because it was the only way for her to get commissions. But because of the way things were, only Rodin’s signature would appear on the pieces, and only he would get the credit for them.

Though she decided to end the affair sometime in the early 1890s, they continued to see each other regularly until 1898.

Descent Into Madness

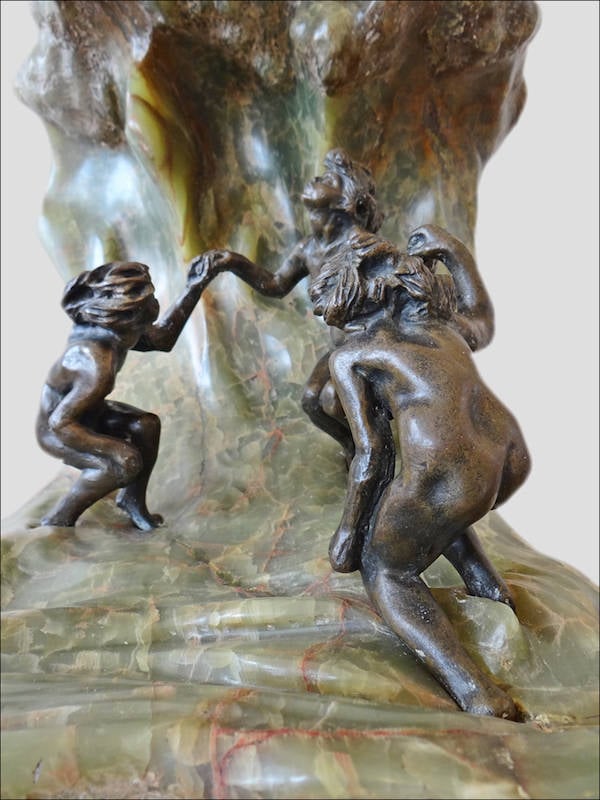

Wikimedia CommonsDétail de “La Vague” (The Wave); Sculpture by Claudel circa 1897.

After completely cutting ties with Rodin, Camille Claudel worked tirelessly on her own. She was poverty-stricken and became more and more of a recluse.

Though Claudel had exhibits at respected salons, she also became increasingly paranoid about Rodin. She felt that he and his “gang” of artist friends were intentionally alienating her from the art world and even became convinced that he wanted to kill her to steal her work.

By 1911, Claudel had completely removed herself from society. She was also systematically smashing her work, still convinced Rodin would come steal her ideas.

In 1913, Camille Claudel was admitted to a psychiatric hospital in Val-de-Marne. It’s been said that her younger brother Paul, a poet and diplomat, had her committed involuntarily and that other artists lamented him for locking up a genius.

But others say that she had become schizophrenic and that institutionalizing her was the only answer.

“It is a tragic story, but it is hard for us to judge now,” said Cecile Bertran, who is the curator of a museum dedicated to Claudel that opened in 2017. “Modern experts have looked at her records and she really was very ill.”

Bertran said that Claudel, still convinced Rodin was after her, would refuse art materials given to her in the asylum. She would never touch clay or create art again.

After World War I broke out, Claudel and the other patients were moved to the asylum of Montdevergues, where she remained for the rest of her.

Camille Claudel died in obscurity on Oct. 19, 1943 at age 78. She was buried in Vaucluse, France.

Camille Claudel Is Rediscovered

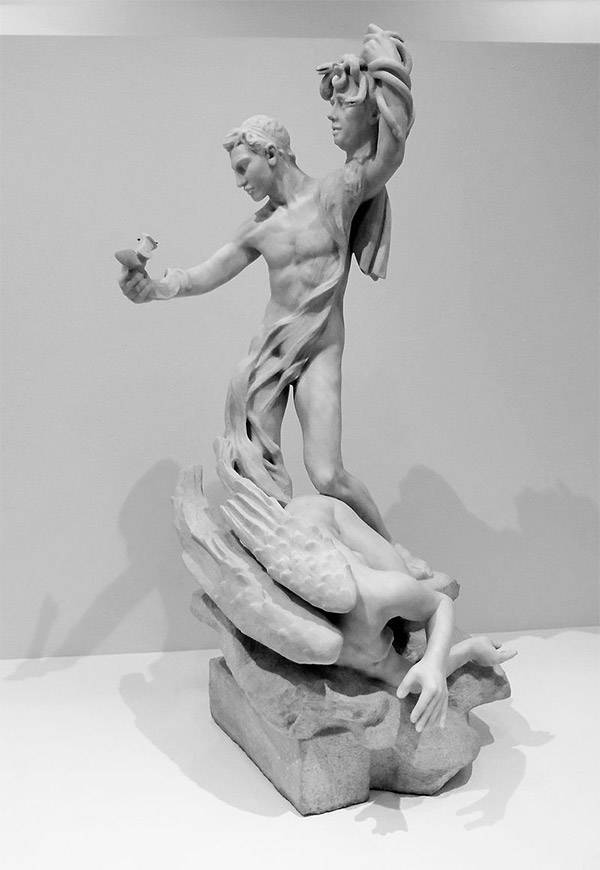

Wikimedia CommonsPerseus and the Gorgon by Camille Claudel.

Because she destroyed a lot of her work, Claudel’s talent as an artist has only been realized recently. The discovery of some of her work and the museum, Musee Camille Claudel, finally gave her credit she lacked for so many years.

The first object in the museum is a monumental bronze sculpture of a couple. Bertran believed it was symbolic of Claudel’s life.

It was originally exhibited as a plaster model, but Claudel never won the commission that would give her the money to cast it in bronze. Years after her death it was cast, but due to poor storage, it was badly damaged.

After learning about Camille Claudel, read about Elisabeth Fritzl, who spent 24 years in her father’s prison. Then read about Audrey Munson, America’s first supermodel who died in a asylum.