The Tk'emlúps te Secwépemc Nation found 215 bodies on the grounds of the defunct Kamloops Indian Residential School using ground-penetrating radar.

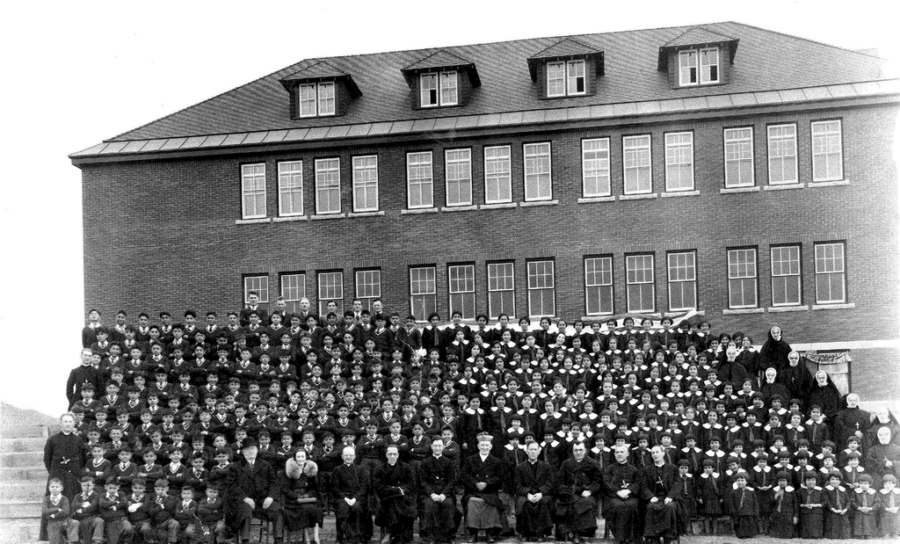

Wikimedia CommonsKamloops Indian Residential School, circa 1930.

The people of the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc Nation in Canada knew that something horrible had happened to their children. Many had gone mysteriously missing after being forcibly enrolled in boarding schools.

But it wasn’t until the discovery of 215 small bodies at the now-defunct Kamloops Indian Residential School that they learned the heartbreaking truth.

“We had a knowing in our community that we were able to verify,” Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc Chief Rosanne Casimir said. “At this time, we have more questions than answers.”

Chasing rumors about unmarked graves at schools like Kamloops — as well as a certainty that the missing children had not simply “run away” — the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc began to search the school grounds with ground-penetrating radar in 2000.

“There had to be more to the story,” Casimir said.

Indeed, the quiet, flat land that surrounded the school hid a terrible truth. Tribal members uncovered 215 bodies of children, some as young as three years old, in unmarked graves spread across the school’s grounds.

“It’s a harsh reality and it’s our truth, it’s our history,” Casimir said. “And it’s something that we’ve always had to fight to prove. To me, it’s always been a horrible, horrible history.”

Archdiocese of VancouverChildren at the school in 1937.

Between 1883 and 1996, Canadian officials forcibly removed nearly 150,000 Indigenous children from their families. They sent them to schools like Kamloops Indian Residential School where Indigenous languages and traditions were banned, and abuse was rampant.

“The whole point was to erase their Indigenous identities,” said Crystal Gayle Fraser, a University of Alberta professor. “These Indian residential schools have often been compared to prisons.”

Garry Gottfriedson, a former student at Kamloops Indian Residential School, which closed in 1978, described an atmosphere of fear and abuse.

“We were told we were ugly. We were made to feel like we were nothing but dirt,” he recalled, calling his time at Kamloops “absolutely terrifying”.

Gottfriedson remarked that he wasn’t surprised to hear that 215 bodies had been discovered on school grounds.

“Sometimes kids would not show up in classroom, they would disappear for the next day and we knew that they were gone, but we didn’t know where they were gone,” Gottfriedson said.

Library and Archive of CanadaChildren in class at a residential school similar to Kamloops circa 1936.

In recent years, the Canadian government has tried to make amends for this horrific chapter in the country’s history. In 2008, the government offered Indigenous people an official apology. And in 2015, Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission determined that the residential schools constituted “cultural genocide.”

That commission also found that 4,100 children had died while enrolled in residential schools from mistreatment, neglect, diseases, or accidents. However, the deaths of the children found at Kamloops were undocumented and not included in that total.

Although the discovery of the remains has brought some closure, it’s also prompted new questions. Indigenous groups in Canada are now calling for a nationwide search of former residential schools.

“It’s absolutely essential that there be a national program to thoroughly investigate all residential school sites in regard to unmarked mass graves,” said Grand Chief Stewart Phillip, President of the Union of British Columbia Indian Chiefs.

Cole Burston/AFP via Getty ImagesA makeshift memorial has been erected at the school to honour the 215 children whose remains were discovered on the property.

Casimir thinks that even the grounds at Kamloops might hide more bodies.

“We have not done all our grounds, and we do know that there is still more to be discovered,” she said.

In addition to searching for more graves, tribal leaders also want an official apology from the Catholic Church. Many of the residential schools — including Kamloops — were run by the Catholic Church. Although Vancouver’s archbishop J. Michael Miller offered an apology, saying that the discovery filled him with “deep sadness”, tribal leaders are waiting for a statement from the Vatican.

Indigenous Relations Minister Carolyn Bennett said that an apology by the Pope would help heal old and deep wounds among Indigenous people in Canada.

“They want to hear the Pope apologize,” she said.

But for now, the focus is on the children. Not all the children who attended Kamloops Indian Residential School were from the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc Nation. Tribal leaders hope to use modern-day forensics to identify their remains and finally send them home.

After reading about the heartbreaking discovery of Indigenous children’s remains in Canada, discover facts about the Native American genocide you never learned in school. Or, see how Canada forced the Inuit people to change their traditions.