Believed to be the site where Jesus and his disciples had the Last Supper just before his crucifixion, the Cenacle in Jerusalem has long been sacred ground for Christians — and some of them left graffiti behind.

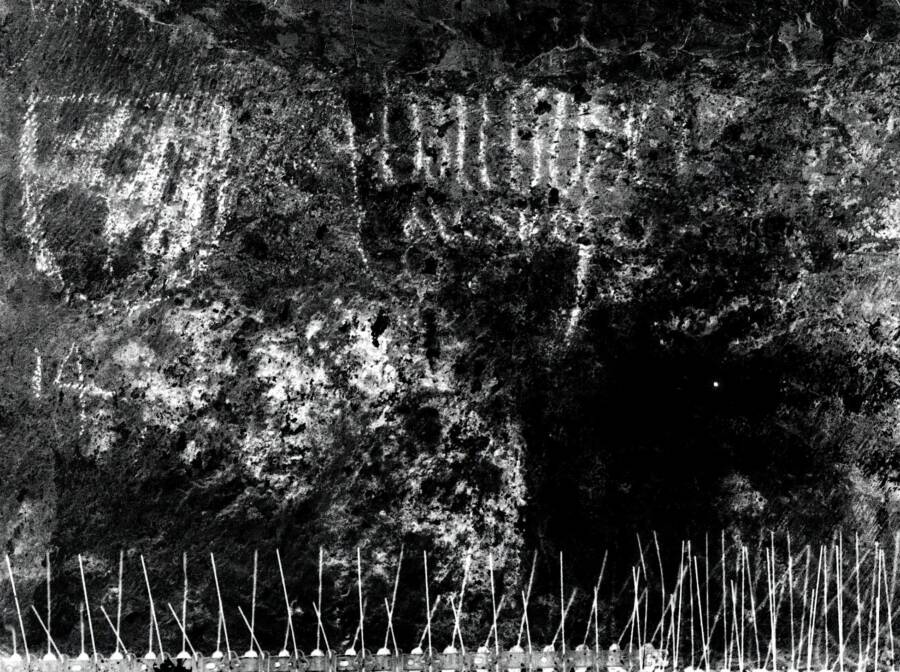

Shai Halevi/Israel Antiquities AuthorityInscriptions, including a coat of arms, which were left by pilgrims at the Cenacle in Jerusalem, the supposed site of Jesus’ Last Supper.

For centuries, the Cenacle in Jerusalem has been considered sacred ground for millions around the world. Christians contend that it’s the site of the Last Supper that Jesus and his disciples shared just before his crucifixion at Golgotha. Meanwhile, Muslims and Jews believe that it’s the tomb of King David.

Thus the site has long drawn countless pilgrims — and as a recent study shows, some of them left their mark.

By using modern technology to examine the building’s walls, researchers were able to decipher a number of inscriptions that were left by medieval pilgrims before being covered up by plaster in the 16th century. The pilgrims who created this graffiti came from a wide variety of places and left behind a fascinatingly disparate collection of notes.

The Graffiti Left By Medieval Pilgrims At The Cenacle In Jerusalem

According to a new study published in Liber Annuus, a journal of theology and Biblical archaeology, the medieval graffiti at the Cenacle was first detected in the 1990s during restoration work. Using modern technology like ultraviolet filters and multispectral photography, researchers have now been able to decipher 30 inscriptions and nine drawings.

Shai Halevi/Israel Antiquities AuthorityA coat of arms with the inscription “Altbach,” which seemingly came from a German pilgrim.

The researchers found that the graffiti had been left by a myriad of different people from various nationalities during the Middle Ages.

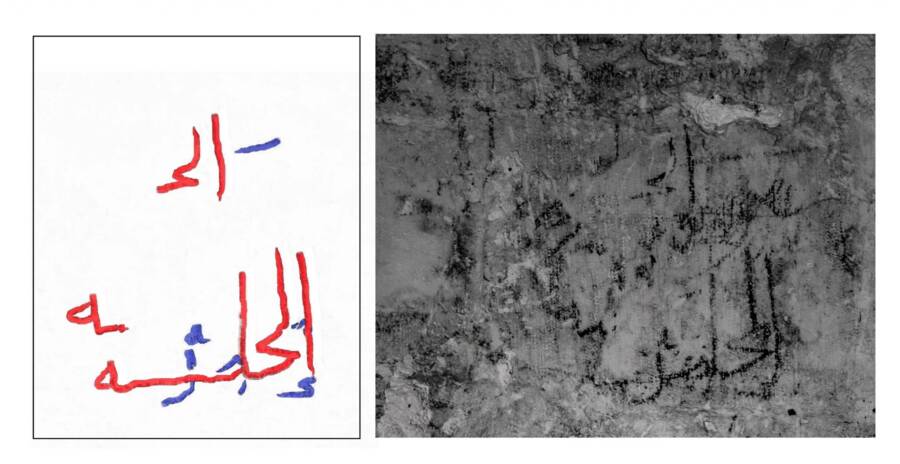

Some of the inscriptions were left anonymously, like the Arabic inscription ending “…ya al-Ḥalabīya,” a seeming reference to the Syrian city of Aleppo, or the Armenian inscription of “Christmas 1300,” which may be related to a famous military victory won by the Armenian King Het’um II in 1299.

Other pilgrims, however, actually left their names. Johannes Poloner, a German pilgrim who traveled to Jerusalem in 1421–22 and wrote a book about his travels, inscribed his name. As did famed Swiss knight Adrian I von Bubenberg, Venetian noble Jacomo Querini, and Franconian count Lamprecht von Seckendorff. Tristram von Teuffenbach, a Styrian nobleman who traveled to Jerusalem in 1436, even left behind a drawing of his coat of arms.

Shai Halevi/Israel Antiquities AuthorityThe graffiti of a pilgrim from Aleppo, in red, which is overlaid with another inscription that hasn’t yet been deciphered.

“The written findings found at the site did not surprise us, the place is known for its historical importance to pilgrims in different historical periods,” study authors Shai Halevi and Michel Chernin told All That’s Interesting in an email. “The aspect that surprised us was the quantity and great detail hidden in the walls, the abundance of characters and languages from different nations that tell in a short word or sentence the hidden historical narrative.”

So why were these pilgrims allowed to leave their inscriptions? And how was the graffiti preserved for hundreds of years?

The History Of The Cenacle, Alleged Site Of The Last Supper

According to researchers, the Cenacle in Jerusalem was under control of the Franciscan Monastery of Mount Sion between the late 14th century and early 16th century, when the inscriptions were made. Some of these inscriptions are quite intricate, and would have taken hours to make, which suggests that the Franciscans were tolerant of the practice.

“The attitude of the Franciscans to this subject was ambivalent,” the researchers wrote.

Heritage Conservation Jerusalem Pikiwiki IsraelThe Hall of the Last Supper on Mount Sion.

But ownership of the Cenacle in Jerusalem changed in the 16th century. After the Ottomans captured the city in 1517, they expelled the Franciscans from Jerusalem and took control of the building. It was Sheikh Aḥmad al-ʿAǧamī who insisted that the sultan Suleiman the Magnificent expel the Franciscans, which is perhaps why someone left an inscription with his name alongside a depiction of a scorpion, a Sufi symbol.

The Ottomans then covered the walls in thick white plaster, hiding the graffiti from view for centuries. Though the medieval inscriptions were first detected in the 1990s, it took another several decades for researchers to understand what they said — a project that is ongoing.

Based on what’s been uncovered so far, the graffiti at the Cenacle in Jerusalem offers a stunning window into the past. There are few things more human than wishing to leave a mark and, thanks to modern technology, the inscriptions left by medieval pilgrims at this holy site can finally be interpreted.

“We are documenting the historical paths along which people have walked and left their mark,” Halevi and Chernin told All That’s Interesting. “This documentation tells a fascinating story that describes the human historical story without judgment, out of respect for those who were here and carved their journeys along my paths. We hope that our documentary contribution will contribute to the recognition and study of history.”

After reading about the medieval graffiti left at the Cenacle in Jerusalem, discover the full story of why Jesus was crucified. Then, learn the truth about what Jesus looked like as well as his real name.