At more than one million hours of use and counting, this bulb proves that they really don't make things like they used to.

Richard Jones/Guinness Book of World RecordsThe Centennial Bulb alight inside Firestation #6 in Livermore, California.

In an otherwise unremarkable little firehouse in Livermore, Calif., there is a light bulb that has been burning since it was first set alight — in 1901.

The Centennial Bulb, as this light has come to be known, is the longest-lasting light bulb of all time. It has been burning continuously since 1901, excluding a short interval in 1976 when the bulb was disconnected from electricity for 22 minutes while the firestation was moved to a different location.

Where did such an incredible bulb come from and how has it been lasting so long?

This Centennial Bulb was manufactured in Shelby, Ohio by the Shelby Electric Company sometime in the late 1890s. It first made its way to Livermore when it was bought in 1901 by Dennis Bernal, owner of the Livermore Power and Water Company. When he sold the company that same year, Bernal donated the bulb to the local firestation.

The bulb was then hung in a hose cart house initially, before being moved to a garage that the fire department used, and then to city hall. Finally, the bulb made its way to what would become its permanent home: Firestation #6.

There the bulb stayed, where it has become a local landmark and point of pride. Though today the bulb has dimmed from the 30-watt output of its beginnings to a comparatively meager four watts (about the output of an average night light), it still continues to burn — more than 116 years and 1 million hours of use later.

Given such accomplishments, the Centennial Bulb was recognized as “the most durable light” by the Guinness Book of World Records in 1972, and is now listed as the “longest burning light bulb.”

Today, people can view the bulb in real time around the world via a live webcam broadcast viewable on the bulb’s official website.

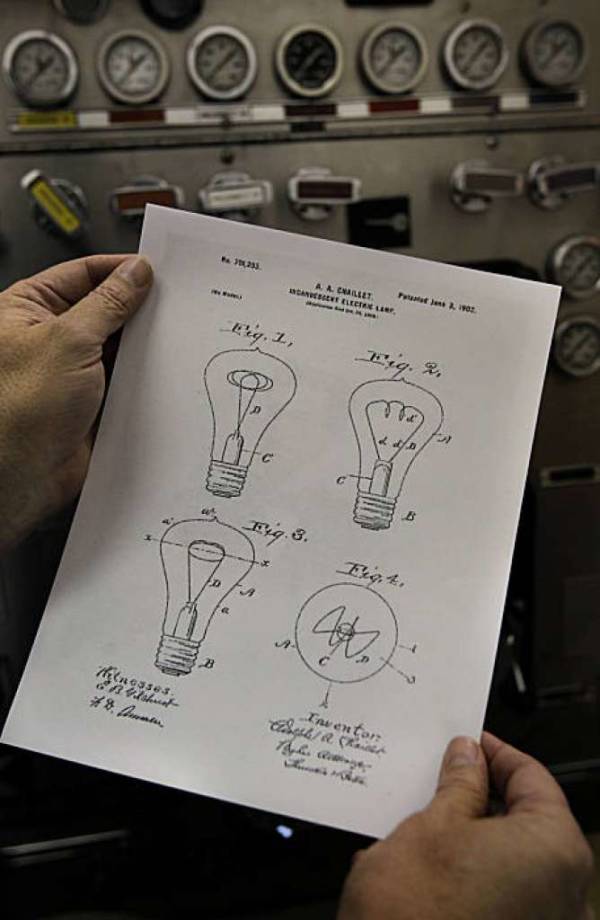

San Francisco ChronicleWhat is known about the design of the Centennial Bulb.

What is so remarkable about this bulb, however, is how unremarkable it actually is. Though researchers are not certain of the exact design of the Centennial Bulb — checking it thoroughly while it is still running is impossible — it is believed to be not much different from any other bulb developed by the Shelby Electric Company at the time of its creation.

Though some of the bulb’s extraordinarily long lifespan may be due to its unique design, it is not unusual for bulbs from that era to burn much, much longer than we are accustomed to.

That’s because this light bulb was manufactured before the life span of light bulbs was artificially set by lighting companies in the 1920s, as many now claim.

It was then that the largest light bulb companies of the time — Philips, Osram, and General Electric — met in Sweden to form Phoebus, a global cartel, according to some researchers.

With this cartel, the companies set light bulb life expectancies at 1,000 hours under the guise that this made them more “efficient” and would heavily fine members who designed light bulbs that exceeded this limit.

In reality, the lighting companies had created this 1,000-hour policy because they had realized that by shortening the life spans of their light bulbs, they could collect more revenue from the same customers who needed to buy new bulbs again and again once their old ones burned out.

Markus Krajewski, a media-studies professor at the University of Basel, in Switzerland, who has researched Phoebus, said, “It was the explicit aim of the cartel to reduce the life span of the lamps in order to increase sales.”

While the Phoebus cartel dissolved only a couple years later, the industry standards it created lived on, and so did its model of “planned obsolescence,” in which products are designed to have an artificially short life span so that companies can generate greater sales.

This model of business came into vogue during the Great Depression, not long after the creation of this cartel, as a way to increase factory jobs by having a higher turnaround of products. However, it quickly became merely a tactic for businesses to increase profits.

Nowadays, the practice of planned obsolescence is commonplace. Many technology and appliance companies, for example, create software and hardware that is hard to repair and is designed to break down or become incompatible with subsequently released products.

This forces consumers to replace their devices much more frequently than people in the past had to, just so that businesses can make more money.

Dan Grebb/FlickrApple products are, by design, notoriously difficult to disassemble and repair.

Tim Cooper, a design professor who heads the sustainable consumption research group at Nottingham Trent University, believes that the only way to solve this problem is through government action.

He believes that minimum standards of durability, repairability, and upgradeability need to be set and that a decrease in taxes on labor and an increase in taxes on energy and raw materials would be the only way to curtail this practice.

He recognizes, though, that these policies will cause a short-term decrease in economic growth, making it an unlikely cause for politicians to champion.

But until drastic changes like these are made to regulate the market, we will likely continue to buy products that have an early death built into their design. And we will keep replacing our light bulbs every year or so, despite the fact that one made in the 1890s has been burning for the last 116 years.

After this look at the Centennial Bulb, read up on Thomas Edison — who didn’t actually invent the light bulb — and five other famous inventors who don’t actually deserve credit for their most well-known creation. Then, learn some of the dark truths about Steve Jobs that explain why we all need to stop idolizing the man behind Apple and the iPhone.