Source: 4 Bit News

Homelessness is a national problem in the United States, and one whose victims are often hidden. They aren’t just the haggard Vietnam vet or the disabled man on the corner asking for assistance; they’re the children and families who couch surf, bounce between friends’ homes, live in cars, subsist in tent cities or stay in hotels.

According to the National Center on Family Homelessness (NCFH), as of November 2014 2.5 million homeless children live across the United States. Without intervention, those are 2.5 million people who could become chronically homeless adults.

Two brothers play cards in the common area of “Nickelsville,” a tent community in West Seattle. The community has relocated throughout the years. Source: Seattle PI

Tent cities popped up as affordable housing options for the extremely poor. Nickelsville houses up to one thousand homeless individuals. Source: Seattle PI

A line outside of a Feed The Children event in Hoffman Estates, Illinois. Source: Slate

Homelessness impacts all of those who experience it, but especially children and in myriad ways. Homeless children are more likely to experience health problems due to dirty living conditions, sleep-deprivation and lack of nutrition. They are four times more likely than other children to suffer from respiratory infections, five times more likely to experience gastrointestinal problems and have three times the rate of emotional and behavioral problems than non-homeless children.

Many suffer from low academic performance levels due to constant relocation, and therefore are more likely to repeat a grade compared to non-homeless children. By the time homeless children are eight years old, one in three will have a major mental disorder.

Source: Mint Press News

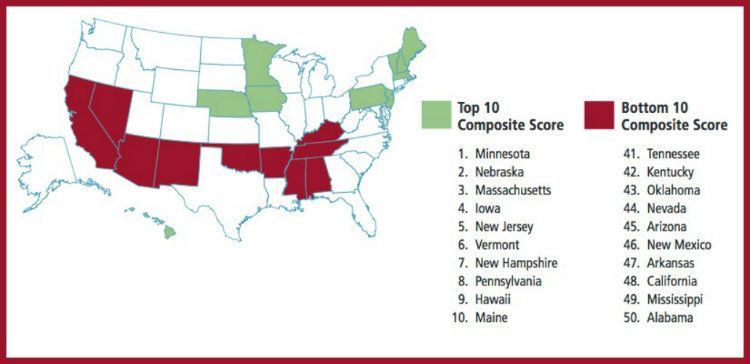

The NCFH’s study analyzed all 50 states and rated them based on the extent of homelessness, children’s well-being, risk for family homelessness and state policies focused on combating the issue.

The worst states for childhood homelessness are Alabama, Mississippi and California. Largely due to massive home foreclosures in 2010, the number of homeless children and families has risen nationally by one million. Now, one in 30 American children doesn’t have a roof over his or her head.

Source: Huffington Post

In a National Low Income Housing Coalition study, researchers determined that only 30 housing units are available for every 100 extremely low-income families. More than one third of families headed by a single mother live in poverty, and an estimated 45 million people lived at or below the federal poverty line in 2013. These families are on the cusp of living on the street, but since they aren’t yet they remain “invisible” to federal bodies tasked with grappling with the homelessness problem.

Homeless encampment under a bridge in Miami. Source: Mint Press News

A young mother sits with her baby in a Tupperware in Tampa, Florida. Source: The New York Times

A child reacts to receiving new clothes at a homeless shelter in Salt Lake City. Source: Deseret News

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development only considers individuals living in shelters to be homeless. Youth living in cars, in tent cities or in motels don’t count. This renders the problem of childhood homelessness less perceptible to governmental authorities and thus makes children more vulnerable to violence as they move through risky situations looking for shelter.

A young child sits on a mattress at a temporary shelter at the Covenant Presbyterian Church in Charlotte, North Carolina. Source: International Business Times

Source: RT

Homeless families sometimes live in cheap motels when they can afford it. Motel rates are often less expensive than home rentals. Source: Al Jazeera

Hotels provide bathrooms and opportunities for showers, which aren’t available in tent encampments or in cars. Source: Lucy Nicholson

Source: The New York Times

The U.S. has a lofty goal of ending childhood homelessness by the year 2020. Spearheaded by the United States Interagency Council on Homelessness, the federal Opening Doors program seeks to increase access to stable and affordable housing, improve health, increase economic security and improve the response system for the homeless. An ideal first step would be to remove the veil that hides America’s homeless youth.

A child at a temporary shelter in a church in Livingston, New Jersey. Source: The New York Times