China has recently done away with its one-child policy. Here's what that policy was and what the change means for China's future.

A Chinese baby in Xian. Image Source: Flickr/Carol Schaffer

China’s 35-year one-child policy is about to come to a close, the state run Xinhua-news agency reported this week. The 1980-enacted policy, which the government claims prevented approximately 400 million births, has met its end as the Chinese state hopes to “improve the balanced development of population” and deal with an aging population, according to a statement released by the Communist Party’s Central Committee.

This is a pretty big deal for a number of reasons. We provide an explainer on the policy — and what’s ahead — below:

What Is China’s One-Child Policy?

The one-child policy is actually just one among a suite of efforts, such as delayed marriage and contraceptive use, that the Chinese government made in the mid-20th century to combat overpopulation in China.

According to the Information Office of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China, “one child for one couple is a necessary choice made under China’s special historical conditions to alleviate the grim population situation.”

Likewise, those who volunteer to have one child are afforded what the Information Office describes as “preferential treatments in daily life, work and many other aspects.”

Does Everyone Have to Follow It?

No. According to the Information Office, the policy was really meant to control population growth in urban localities, where “economic, cultural, educational, public health and social security conditions are better.”

Exceptions to the rule are made for couples living in agricultural and pastoral areas, as well as sparsely populated minority areas, including Tibet and the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. Likewise, if both parents have a first child with disabilities, they are allowed to have a second child.

Tibetans are not subject to the one-child policy. Image Source: Flickr/Wonderlane

More recently, in 2013 the Chinese government announced that couples were allowed to have two children if either parent was an only child.

What If A Family In China Had Twins Under The One-Child Policy?

That’s not a problem. While many stress the one child component of the policy, it’s better to understand it as a one birth per family rule. In other words, if a woman gives birth to twins or triplets in one birthing, she won’t be penalized in any way.

If you think this loophole may have increased demand for twins and triplets, you’re right. A few years ago, southern Chinese newspaper Guangzhou Daily conducted an investigation in which they found that some private hospitals in Guangdong province were providing healthy women with infertility medicines to stimulate ovulation and increase the chance of having twins or triplets, ABC News reported. The pills are dubbed “multiple baby pills” in Chinese, and if taken improperly can have some serious, negative side effects.

What Happens If You Break China’s One-Child Policy?

It depends. Family planning officials are charged with regularly checking menstrual cycle and pelvic-exam results of every woman of childbearing age in a given area. If a family is found in violation of the policy — and it applies to them — they are subject to a number of punishments, which usually depend on their connections and wealth.

If a second child has been born in an urban area, for example, his parents will either have to pay a social upbringing fee, or the child will not receive a household register. The social upbringing fee is usually several times as much as the family’s annual average income, and the household register is something like a birth certificate. If a child lacks a household register, he or she cannot receive social insurance or go to school. These children are known as “heihaizi” or “black children,” and have few, if any rights.

The Danshan, Sichuan Province Nongchang Village people Public Affairs Bulletin Board in September 2005 noted that RMB 25,000 in social compensation fees were owed in 2005. Thus far 11,500 RMB had been collected leaving another 13,500 RMB to be collected. Image Source: Wikipedia

If a civil servant breaks the policy, he or she will receive a punishment, ranging from a demerit to discharge.

Sometimes, however, those who are found with a second child — or pregnant with a second child — can be forced to have an abortion, even late term, or be sterilized. According to Chinese Health Ministry data released in March 2013, 336 million abortions and 222 million sterilizations have been carried out since 1971.

Census data reveals that Chinese officials don’t always catch the rule breakers, though: in 1990, for example, the census recorded 23 million births. In 2000, the census put the number of 10 year olds at 26 million, which according to Telegraph Beijing reporter Malcolm Moore suggests that “at least three million babies…escaped the notice of family planning officials.”

Why Did China Impose A One-Child Policy In The First Place?

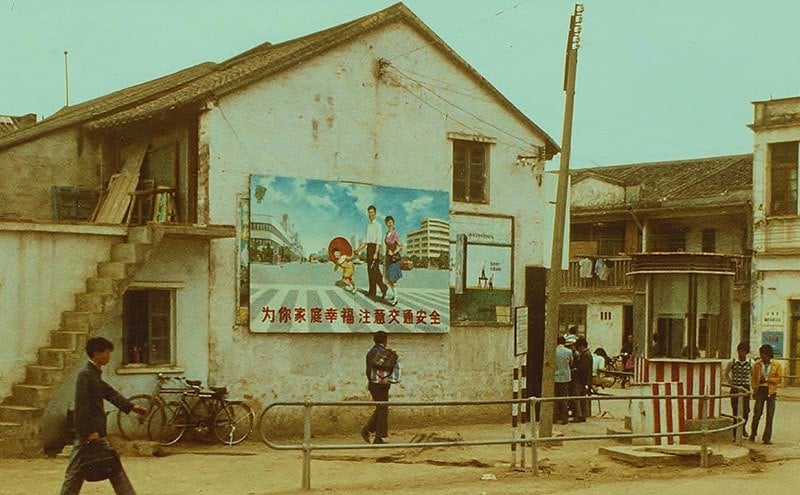

“Carry out family planning, implement the basic national policy” Image Source: Flickr/Zhou Yuwei

The late 70s were a pivotal time in Chinese history. Chinese Communist revolutionary and Chairman of the Communist Party of China Mao Zedong died in 1976, and the Cultural Revolution — a mass purge of anyone or anything that were believed to threaten Communist ideology — died along with him.

At that point, the Chinese population had doubled to 940 million people, corresponding with a recovery from the 1958-1962 famine, as well as Mao’s encouragement that citizens have as many children as possible to “empower” the country.

Earlier attempts to quell that growth — such as advocating for family planning and contraception use in the 1960s, and in 1970 encouraging people to marry later and have only two children — had failed, and emerging discourse about the relationship between population and economic growth got top Chinese officials seriously worried about China’s future.

The fear was that, according to the Information Office, given China’s weak foundation, vast scale, massive population and low ratio of cultivated land, overpopulation would reduce quality of life and potential for economic growth. It was therefore necessary “for the development of population to be coordinated with the development of the economy, society, resources and environment,” wrote the Information Office.

With those circumstances in mind, economic reformer Deng Xiaoping introduced the one-child policy as a then-temporary measure to “deal with the population problem in the overall context of…national economic and social development,” the Information Office wrote.

Thus in 1979, the plan was officially adopted, and enacted in September 1980.

What Are Some Of The Consequences Of Such A Policy?

A happy family with one child, taken in 1982. Image Source: Wikimedia

What was meant to be a one-generation only policy to help alleviate social, economic and environmental problems in China generated an array of its own problems that span across multiple domains, and generations:

For women

As already mentioned, one of the most obvious problems of the policy is that it is not uniformly enforced, and tends to hurt the poor more than it does the wealthy and well-connected. For example, wealthier families can simply pay fines, travel overseas to have the second child or bribe officials to skip out on the rule. If the family is poor and cannot afford to pay the fine, the woman’s body can be punished in the form of a forced abortion or sterilization. While the Chinese government outlawed the use of physical force to make a woman submit to an abortion or sterilization in 2002, it has been criticized for not enforcing it.

Likewise, Chinese author Ma Jian says that high rates of female suicide are the result of such a policy. Wrote Jian for The New York Times, “It is not surprising that China has the highest rate of female suicide in the world. The one-child policy has reduced women to numbers, objects, a means of production; it has denied them control of their bodies and the basic human right to determine freely and responsibly the number and spacing of their children.”

Jian — along with the U.S. State Department, U.K. Parliament and Amnesty International — has declared that the policy effectively encourages female infanticide, as families feel “pressure to ensure that their only child is a son.” While female infanticide has occurred in China throughout its history as the Chinese have a historical cultural preference for producing male heirs, Jian argues that because of this policy women “often choose to abort baby girls or discard them at birth,” which has “skewed China’s sex ratio to 118 boys for every 100 girls.” In some districts, this skew is as high as 150 boys to every 100 girls. For comparison’s sake, in a natural state the sex ratio is generally 105 boys to every 100 girls.

For men

Image Source: Flickr/Ernie

Before a “woman dearth,” China also faces the problems that accompany the presence of “surplus men.” By 2020, it is expected that there will be between 30 and 35 million more Chinese men of marrying age than women, a gap which comes with social consequences. In the book Unnatural Selection, for example, author Mara Hvistendahl writes that these gender-imbalanced societies are and have historically not been good places to live, as they are often unstable and occasionally violent.

Hvistendahl likewise adds that since it’s hard to find a wife, men are starting to buy or bid for them, which means that marriage is increasingly associated with socioeconomic status. For the “surplus” men who cannot find a spouse or afford to buy one — whom Hvistendahl states tend to fall into lower socioeconomic rungs — the risk of engaging in violent behavior is more likely.

For children

As already mentioned, just because a one-child policy is imposed does not mean that families will simply stop having second and third children; they will just try to hide it. One way to conceal a second child is by not reporting their birth to authorities, effectively rendering these children “heihaizi.” This means that these children do not legally exist, and therefore cannot access most public services, or receive protection under the law.

This black-listed status carries on into adulthood, where they are not permitted to apply for work, get married or start a family, or join the military. This means that the likelihood of working in grey or illicit markets — such as organized crime, prostitution and drug dealing — is higher for heihaizi, the majority of whom are female.

For the economy

A Chinese silk factory. Image Source: Flickr/Joriz de Guzman

Plainly put, China’s population is getting old. By the middle of the 21st century, more than a quarter of the Chinese population will be 65 or older, which means that China faces what has been called the 4-2-1 problem.

In a nutshell, the 4-2-1 problem states that since most Chinese citizens today don’t have siblings, they will likely have to take care of two parents and four grandparents (4 grandparents – 2 parents – 1 child), which will put an additional strain on a younger generation feeling pressured to contribute to China’s ambitious economic growth models.

The policy has also had a negative impact on labor. In 2014, the Washington Post reported that China’s working age population fell for the third straight year, and is slated to fall even further as China’s aging populations retire from the workforce — as much as 10 million per year starting in 2025. Lacking this chunk of wealth-generating labor, before an aging population and a low fertility rate, questions of how the Chinese government will provide various social programs and healthcare — while also staying competitive in international markets — become that much more acute, and hard to solve.

Did Anything Good Come From China’s One-Child Policy?

It depends on whom you ask. Some Chinese Communist Party officials like to say that the policy has prevented 400 million births, therefore rendering the one-child policy a “success.”

A Chinese harvest image. Image Source: Flickr/Jimmie

Others, such as Chinese affairs expert Weng Fang describe the policy as “a textbook example of bad science combined with bad politics” which came with countless human rights violations and economic and demographic ripple effects.

What Do The Chinese Think Of The Policy?

Again, it depends on whom you ask. If surveys are to be believed, a 2008 Pew Research Center survey revealed that 76 percent of the Chinese population approve of the policy. It should be noted that the sample size of this survey was 3,212, and that the area covered within the sample represents 42 percent of the country’s adult population.

Why Is The Chinese Government Ending It Now?

First, a caveat: the Chinese government is still imposing a limit on how many children a family can have, but has increased that cap to two children.

As outlined above, time has shown the policy’s massive social and economic consequences. The government needs to find a way to pay for the costs that come with slowing economic growth and increased spending on healthcare and retirement programs for the elderly, Huffington Post China correspondent Matt Sheehan wrote.

Likewise, Sheehan adds that it seems the Chinese government has realized that the social costs of the policy — including female infanticide, self-selective abortions and crime borne from a generation of bachelors — outweigh whatever benefits the one-child policy may have offered.

What Does This Mean Going Forward?

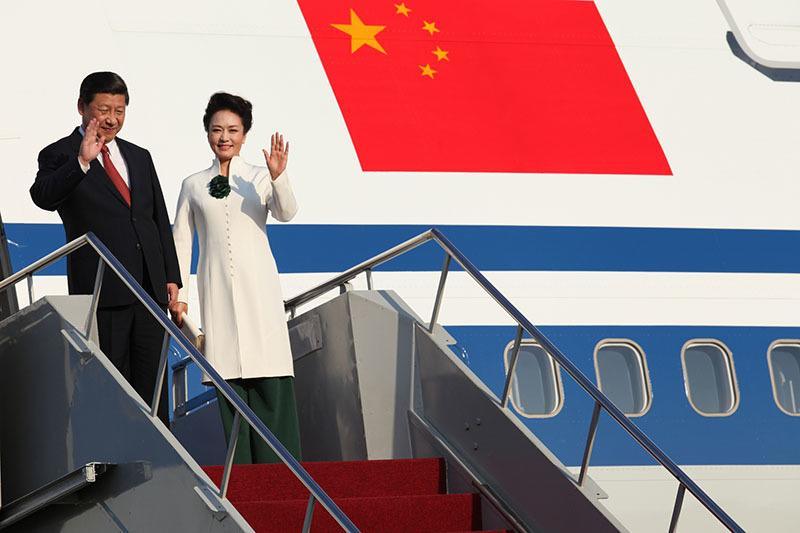

Chinese president Xi Jinping (left) Image Source: Flickr/APEC

First of all, experts are out on if this shift will actually solve the problems China currently faces, as an increasingly urbanized, wealthy China means that both a need and a desire for second and third children has naturally fallen. With that said, Quartz senior Asia correspondent Adam Pasick has laid out a few projections:

So there you have it. In short, government interventions can actually exacerbate problems which they hope to solve — and China’s one-child policy is one of many examples.

Be sure to check out our posts on China’s pollution problem and watch this Journeyman Pictures documentary on the high social costs of the One Child policy: