What Are Some Of The Consequences Of Such A Policy?

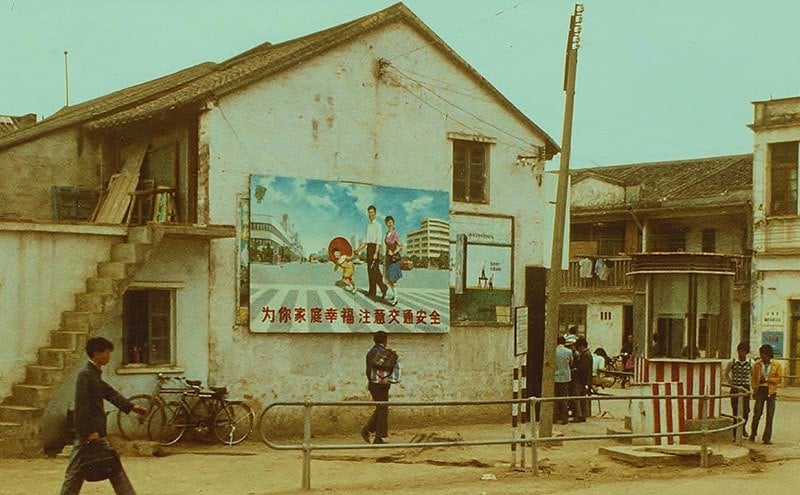

A happy family with one child, taken in 1982. Image Source: Wikimedia

What was meant to be a one-generation only policy to help alleviate social, economic and environmental problems in China generated an array of its own problems that span across multiple domains, and generations:

For women

As already mentioned, one of the most obvious problems of the policy is that it is not uniformly enforced, and tends to hurt the poor more than it does the wealthy and well-connected. For example, wealthier families can simply pay fines, travel overseas to have the second child or bribe officials to skip out on the rule. If the family is poor and cannot afford to pay the fine, the woman’s body can be punished in the form of a forced abortion or sterilization. While the Chinese government outlawed the use of physical force to make a woman submit to an abortion or sterilization in 2002, it has been criticized for not enforcing it.

Likewise, Chinese author Ma Jian says that high rates of female suicide are the result of such a policy. Wrote Jian for The New York Times, “It is not surprising that China has the highest rate of female suicide in the world. The one-child policy has reduced women to numbers, objects, a means of production; it has denied them control of their bodies and the basic human right to determine freely and responsibly the number and spacing of their children.”

Jian — along with the U.S. State Department, U.K. Parliament and Amnesty International — has declared that the policy effectively encourages female infanticide, as families feel “pressure to ensure that their only child is a son.” While female infanticide has occurred in China throughout its history as the Chinese have a historical cultural preference for producing male heirs, Jian argues that because of this policy women “often choose to abort baby girls or discard them at birth,” which has “skewed China’s sex ratio to 118 boys for every 100 girls.” In some districts, this skew is as high as 150 boys to every 100 girls. For comparison’s sake, in a natural state the sex ratio is generally 105 boys to every 100 girls.

For men

Image Source: Flickr/Ernie

Before a “woman dearth,” China also faces the problems that accompany the presence of “surplus men.” By 2020, it is expected that there will be between 30 and 35 million more Chinese men of marrying age than women, a gap which comes with social consequences. In the book Unnatural Selection, for example, author Mara Hvistendahl writes that these gender-imbalanced societies are and have historically not been good places to live, as they are often unstable and occasionally violent.

Hvistendahl likewise adds that since it’s hard to find a wife, men are starting to buy or bid for them, which means that marriage is increasingly associated with socioeconomic status. For the “surplus” men who cannot find a spouse or afford to buy one — whom Hvistendahl states tend to fall into lower socioeconomic rungs — the risk of engaging in violent behavior is more likely.

For children

As already mentioned, just because a one-child policy is imposed does not mean that families will simply stop having second and third children; they will just try to hide it. One way to conceal a second child is by not reporting their birth to authorities, effectively rendering these children “heihaizi.” This means that these children do not legally exist, and therefore cannot access most public services, or receive protection under the law.

This black-listed status carries on into adulthood, where they are not permitted to apply for work, get married or start a family, or join the military. This means that the likelihood of working in grey or illicit markets — such as organized crime, prostitution and drug dealing — is higher for heihaizi, the majority of whom are female.

For the economy

A Chinese silk factory. Image Source: Flickr/Joriz de Guzman

Plainly put, China’s population is getting old. By the middle of the 21st century, more than a quarter of the Chinese population will be 65 or older, which means that China faces what has been called the 4-2-1 problem.

In a nutshell, the 4-2-1 problem states that since most Chinese citizens today don’t have siblings, they will likely have to take care of two parents and four grandparents (4 grandparents – 2 parents – 1 child), which will put an additional strain on a younger generation feeling pressured to contribute to China’s ambitious economic growth models.

The policy has also had a negative impact on labor. In 2014, the Washington Post reported that China’s working age population fell for the third straight year, and is slated to fall even further as China’s aging populations retire from the workforce — as much as 10 million per year starting in 2025. Lacking this chunk of wealth-generating labor, before an aging population and a low fertility rate, questions of how the Chinese government will provide various social programs and healthcare — while also staying competitive in international markets — become that much more acute, and hard to solve.