A favorite haunt of both mobsters and celebrities in the mid-20th century, the Copacabana has since been featured in several Mafia movies that have helped keep its legacy alive.

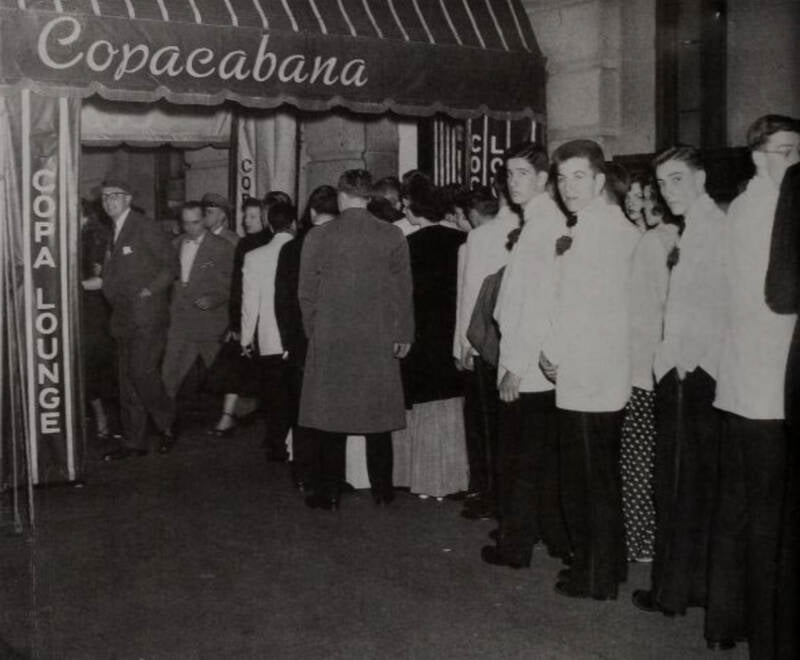

Mickey Podell-RaberA line outside the Copacabana nightclub during prom season.

“Her name was Lola, she was a showgirl/With yellow feathers in her hair and a dress cut down to there/She would merengue and do the cha-cha/And while she tried to be a star/Tony always tended bar…”

So goes the opening to Barry Manilow’s hit 1978 song “Copacabana (At the Copa),” a catchy ear worm of a song that, upon first listen, seems to be an upbeat recollection of a night out at the club, a showgirl named Lola, and her lover Tony. A closer look at Manilow’s lyrics, however, would reveal a much darker story starting with the second verse and the introduction of Rico, a wealthy and violent man who, in a fight, kills Tony. Lola, 30 years on, still wears her dancing dress, but spends her days drinking herself “half-blind” reminiscing on what could have been.

It might seem an odd twist for what is otherwise a fun disco tune about one of New York’s hottest celebrity hangouts. The real Copacabana was, after all, immensely popular. But the song’s lyrics, while telling a fictional tale, do hint at a darker truth about the nightclub and its strong ties to the mob. When the club first opened in 1940, Monte Proser served as its public face — but his partner, mobster Frank Costello, was far from a clean cut businessman.

Dive into the history of New York’s famous Copacabana nightclub through our collection of photos below, and read on to learn about one of the world’s most iconic clubs.

The Golden Beginning Of The Copacabana Nightclub

The original Copacabana nightclub opened its doors on Nov. 10, 1940, at 10 East 60th Street in Manhattan, just off Fifth Avenue.

Broadway impresario and press agent Monte Proser had dreamed up the idea of the club, a Brazilian-themed hotspot with glitzy décor, chorus lines, Latin orchestras, Chinese food — anything he considered exotic and upscale. His name was on the lease, and he served as the club's manager and public face. There was one challenge, though: the mob was buying up any nightclubs they could find to fund their business.

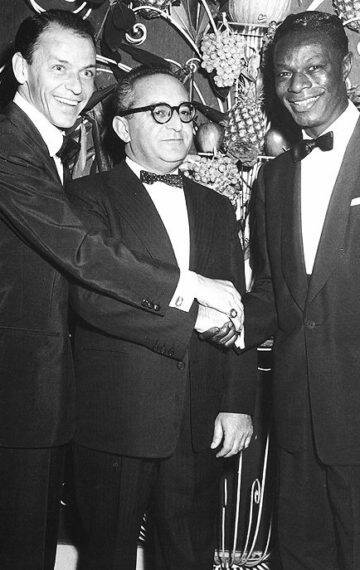

Jim ProserFrank Sinatra, Monte Proser, and Nat King Cole.

Proser was in a difficult position. He didn't want to work with the mob — most people didn't — and he knew if he opened a club, the mob would come knocking. But according to his son Jim Proser, Monte was given what he felt was a golden opportunity.

"The story that nobody knew except my father was that Frank Costello didn't like being a gangster," Jim Proser wrote in his blog. "He wanted to be a businessman like my father. He just wanted to hang out at the Copa, go to the Belmont racetrack, and bet on the ponies. For this reason, my father dealt with Frank and his gangster friends for 35 years — and managed to help many people."

Whether Frank Costello really dreamed of a simpler life is up for debate — gangsters like Albert Anastasia were certainly welcome at the Copa — but Proser seemingly believed that was the case. So, a partnership formed between them, though not without its caveats.

For one, Costello wasn't a hands off business partner. He installed one of his men, Jules Podell, a tough-talking operator with a criminal past, to manage the frontline operations.

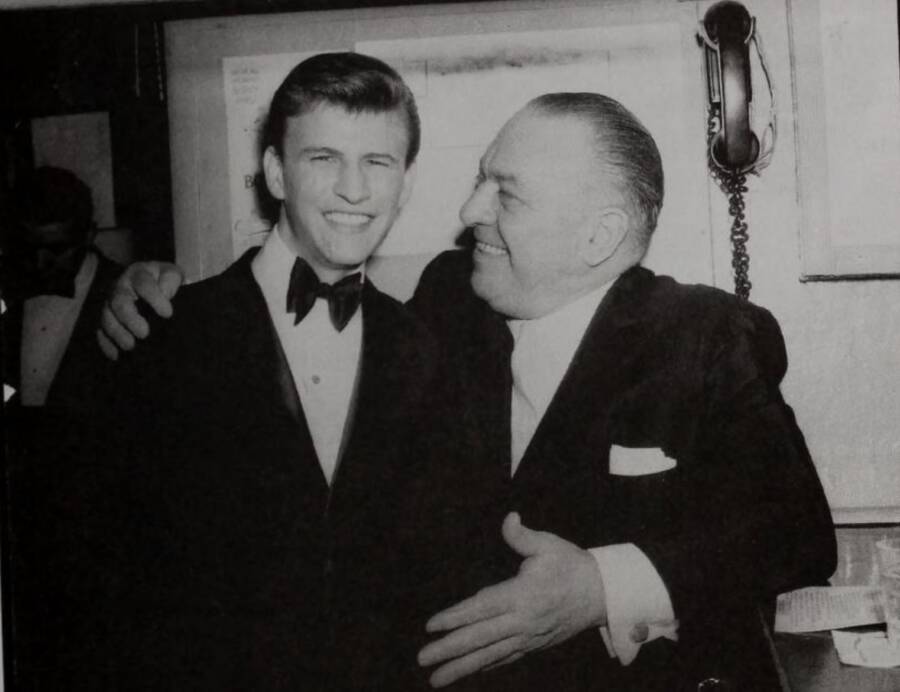

Mickey Podell-RaberJules Podell playing the vibes with the Copa's band.

"Monte Proser fronted the club in the beginning while Jules Podell and Jack Entratter were managing and running it," music agent Frank Military once said, according to Mickey Podell-Raber, Jules Podell's daughter, in The Capo: Jules Podell and the Hottest Club North of Havana. "The word on the street was that Frank Costello had a piece of the Copa. But Podell was the one who ran the day-to-day operations of the club."

Podell turned the Copa into a major cash cow, and although the club faced some tax problems and a racketeering investigation in 1944, it managed to skirt by unscathed. Police and city officials ultimately lowered the pressure, and Podell was able to register as the club's official manager in 1948.

The Golden Age Of Entertainment

Between the 1940s and the 1960s, the Copa was a make-or-break venue for up-and-comers and superstars alike. Early headliners included Shep Fields, then legends like Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis, who made their New York debut at the Copa in 1949. Other notable names included Frank Sinatra, Sammy Davis Jr., Nat King Cole, Jimmy Durante, Perry Como, and Peggy Lee, among many others.

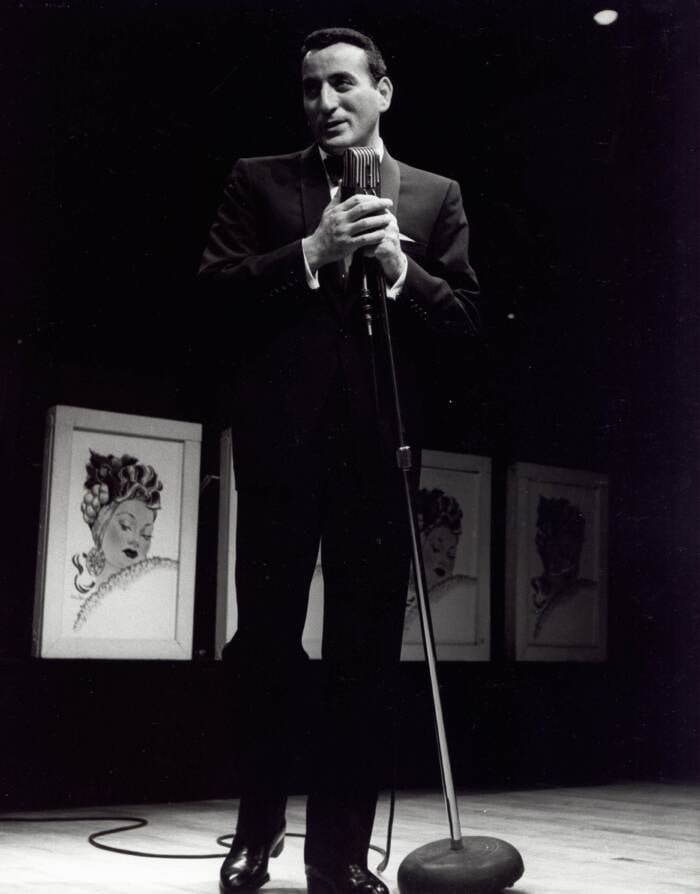

ZUMA Press, Inc./Alamy Stock PhotoTony Bennett performs at the Copacabana nightclub in March 1956

The club wasn't without controversy, though. Early on, Podell enforced a strict "no Blacks" door policy, which infamously barred Harry Belafonte, at the time a member of the U.S. Navy, in 1944. Podell's position on this later changed, thanks in part to Monte Proser's urging. According to Proser's son, Monte was accepting of all kinds of performers and actively tried to support them.

"Monte took them under his wing and, if required, making sure they had a little 'walking around money' in their pocket. It didn't matter what color their skin was, their sex, or whom they chose to love. He didn't care about any of that," Jim Proser stated.

Indeed, Podell changed the policy and Belafonte eventually returned to the Copa as a headliner in the 1950s. And when Sammy Davis Jr. headlined in 1964, he broke attendance records. Eventually, come July 1965, the Copacabana was debuting Motown acts like The Supremes, Martha and the Vandellas, and Marvin Gaye. Despite the club's overall success, though, it did still gain some notoriety for an infamous race-related incident in 1957.

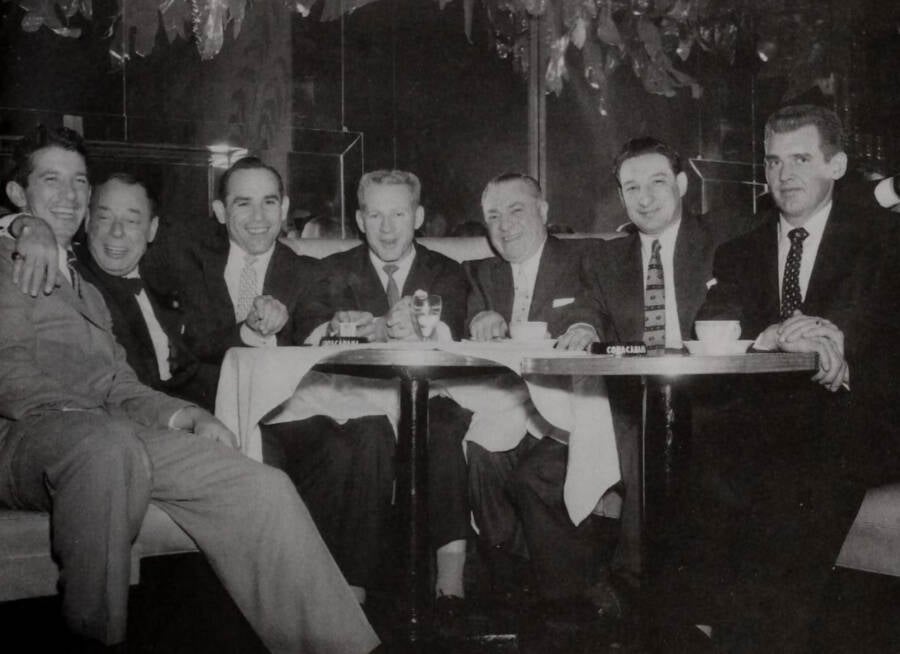

Mickey Podell-RaberBilly Martin, Joe Lewis, Yogi Berra, Whitey Ford, Jules Podell, a friend, and Don Larson at the Copacabana.

On May 16, players for the New York Yankees — Mickey Mantle, Whitey Ford, Hank Bauer, Yogi Berra, Johnny Knucks, and Billy Martin — were at the club to celebrate Martin's birthday. Sammy Davis Jr. was headlining that night, but at some point during the performance drunk audience members began heckling him and throwing out racial slurs. The Yankees, and Martin in particular, grew angry with the crowd, especially since they had just welcomed Elston Howard to the team.

The Yankees and the drunkards got into a physical altercation, which naturally became front page news the next day. Several of the Yankees were fined, and one of the drunks — a deli owner from the Bronx — received a concussion and a broken jaw, prompting him to sue Bauer for aggravated assault. The case was thrown out due to insufficient evidence, but the incident did ultimately lead to Martin being traded from the Yankees to the Kansas City Athletics.

Still, it did little to affect the club's business or reputation. Come the 1970s, though, the Copacabana started to decline, partly due to Podell's death in 1973 and the three-year gap in operations that followed.

The Decline Of The Copacabana And Its 21st Century Reopening

Warner Bros. PicturesA still from the mob movie Goodfellas, which featured an iconic scene at the Copacabana.

Around the same time as the Yankees brawl, though completely unrelated, Frank Costello retired from the mob after surviving an assassination attempt. So, between 1957 and 1972, mob control over the Copa's operations fell to "Crazy Joe" Gallo — who was then murdered in Little Italy while celebrating his 43rd birthday. A year later, Podell also died — not of murder — and the club temporarily shut down.

It took a full three years before the club reopened in 1976, at the peak of the disco era. During this period, Barry Manilow recorded the hit song "Copacabana (At The Copa)," which also served as the inspiration for a made-for-TV movie starring Manilow, set at the club.

Even with Manilow's hit bringing more attention back to the Copa, though, it was clear that the club's heyday was firmly in the past.

Darryl Brooks/Alamy Stock PhotoThe Copacabana in New York after its 2012 reopening.

The Copacabana moved from its original location to 617 West 57th Street in 1992. The club then moved locations again in 2001, when the building's lease was terminated early so that office towers could be built at the location. Construction of the New York City subway's 7-Line in 2007 once again forced the club to relocate, but this time it remained closed for four years.

Copacabana reopened to the public in July 2011, though by this point it was similar to its first incarnation in name only. A final relocation and reopening occurred between 2020 and 2022, due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Today's Copacabana is overseen by Ruben Rubin Cabrera, who converted his event space in Hell's Kitchen into the famous club — although it has more in common with its late '70s disco revival than its '40s golden years.

It bears the name, but the Copa is now, in a way, much like the Ship of Theseus: If a club changes owners and locations several times, is it still the same club?

In the gallery above, take a look back in time and explore the golden years of the Copacabana nightclub.

After this look inside the Copacabana nightclub, discover the true story of Henry Hill, the real-life gangster who inspired the movie "Goodfellas." Or, discover the stories of some of history's most infamous mob wives, including Hill's wife Karen Friedman Hill.