In 1826, several West Point cadets snuck alcohol onto campus to celebrate Christmas — but the so-called Eggnog Riot quickly got out of hand and 19 cadets were expelled.

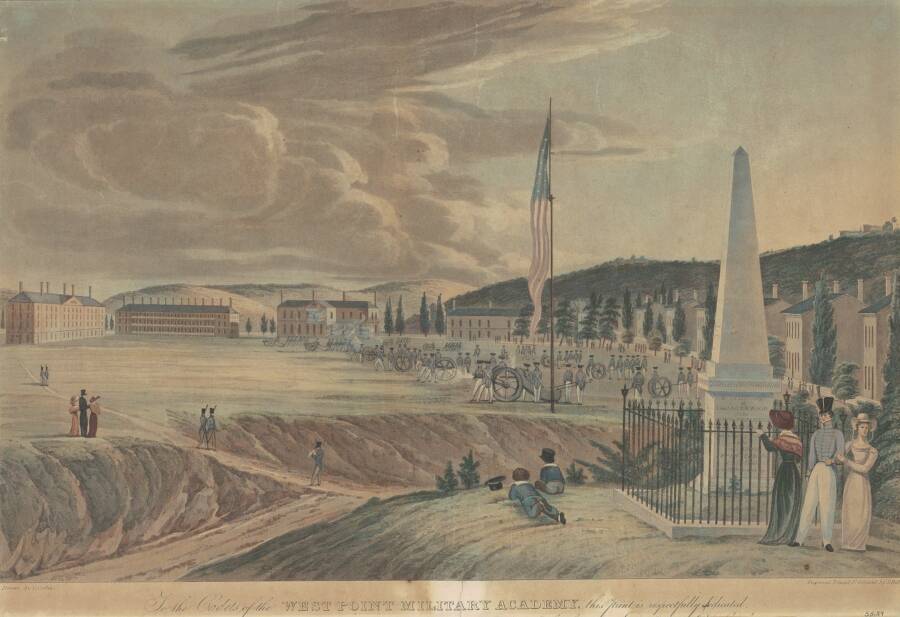

Public DomainWest Point, circa 1828.

There is such a thing as too much holiday cheer. In 1826, an event known as the Eggnog Riot began at the United States Military Academy at West Point when cadets, upset by a recent alcohol ban, smuggled alcohol into their Christmas party. The festivities spread across the academy, drawing more and more students into the boisterous celebration.

As the night wore on, the noise attracted the attention of faculty members who tried to put an end to things. Enraged by the intervention, a group of cadets armed with dirks, bayonets, and pistols fought back. The Christmas celebration quickly spiraled into chaos, with the cadets vandalizing the barracks and attacking their instructors.

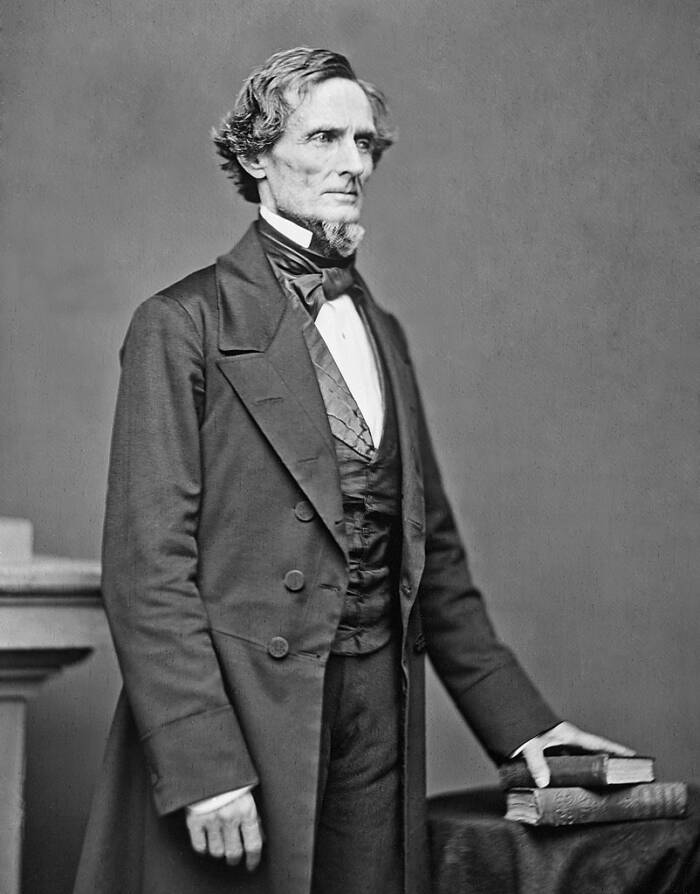

By Christmas morning, the riot was quelled. But almost a third of West Point’s 260 cadets had been involved in the so-called “grog mutiny,” including the future president of the Confederacy, Jefferson Davis.

This is the story of the Eggnog Riot, from how it began, to what punishment the participants faced, to the changes West Point made in the aftermath to ensure that such a riot never happened again.

How A Ban On Alcohol Led To The ‘Grog Mutiny’ At West Point

Today, West Point is known as an esteemed military academy with notable alumni like Dwight D. Eisenhower and Ulysses S. Grant. But it was a humble institution when it first opened in 1802. It was only after the War of 1812 that Congress began to take West Point seriously, and Colonel Sylvanus Thayer was appointed as superintendent in 1817 in order to improve the school.

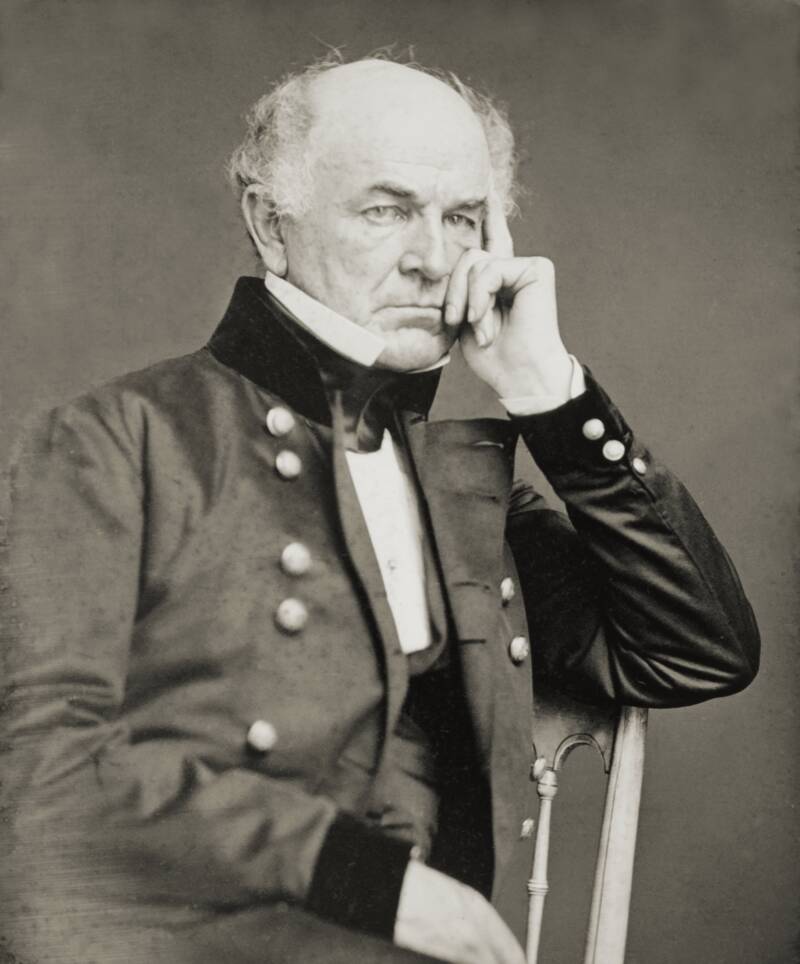

Public DomainPortrait of Sylvanus Thayer, the U.S. Military Academy superintendent at the time of the eggnog riot.

Though Thayer had allowed alcohol at parties in the past, he changed his tune in 1825. The school’s Fourth of July festivities that year had devolved into disorder, and Thayer outright banned “any spirituous or intoxicating liquor” on campus from that point on. That meant that Christmas 1825 and Fourth of July 1826 were alcohol-free. But West Point cadets were determined to smuggle in “intoxicating liquor” for Christmas 1826.

The West Point cadets soon devised a plan to smuggle alcohol onto campus to mix with their traditional eggnog, a popular holiday drink made of eggs, milk, cream, sugar, and spices.

A few days before Christmas, a number of cadets put their plan into action. They procured whiskey, brandy, rum and wine from various taverns in the area, with three cadets even rowing across the Hudson River to obtain several gallons of whiskey. The alcohol then was hidden across campus in anticipation of the festivities on Christmas Day.

With their prize in hand, the cadets began to plot their Christmas party. The illicit festivities would begin on Christmas Eve in the North Barracks. But unfortunately for the cadets, their scheme would have huge consequences.

The Eggnog Riot Spreads Across West Point

The Christmas party that would become the Eggnog Riot began on Dec. 24, 1826. It started in Room No. 28 in the North Barracks, and soon spread to Room No. 5. Cadets, drawn by the promise of spiked eggnog, began to multiply. At one point, cadet David M. Farrelly even kept the party going by showing up with yet another gallon of whiskey.

The party eventually became loud enough to catch the attention of faculty member Captain Ethan Allen Hitchcock. Around 4:00 a.m. on Christmas Day, Hitchcock admonished the drunk cadets of Room No. 28 — and ordered them all back to their rooms. Then, hearing noise in an adjoining bedroom, Hitchcock found three more drunken cadets — two of whom tried to hide under a blanket, and one of whom tried to hide his face with his hat.

Public DomainCaptain Ethan Allen Hitchcock, as seen decades after the Eggnog Riot of 1826.

Enraged by Hitchcock’s interruption, several of the cadets started to organize their revenge against the officer. “Get your dirks and bayonets… and pistols if you have them. Before this night is over, Hitchcock will be dead,” one of the cadets cried, according to Smithsonian Magazine.

Hitchcock, meanwhile, had gone back to his room to try and go to sleep, but a series of repeated knocks on his door kept him up. The Eggnog Riot was still in swing, and when Hitchcock finally got out of bed he saw Jefferson Davis — a known campus troublemaker and the future presidency of the Confederacy — heading to Room No. 5.

Unbeknownst to Davis, Hitchcock was right behind him when he burst into Room No. 5 shouting: “Put away the grog boys! Captain Hitchcock’s coming!”

Public DomainBefore he was president of the Confederacy, Jefferson Davis was a participant in the 1826 Eggnog Riot.

Hitchcock ordered the cadets to bed. Jefferson Davis obeyed, but drunken cadets elsewhere weren’t as accommodating.

Indeed, Hitchcock’s fellow officer Lieutenant William A. Thornton had come across his own problems. Asleep at the beginning of the Eggnog Riot, Thornton awoke to the sound of merrymaking and went to investigate. Upon leaving his room, two cadets began attacking him. One threatened him with a sword; the other hit him with a plank of wood, knocking him off his feet.

With Thornton down, the angry and drunken cadets continued on their search for Hitchcock. They eventually found him in North Barracks Room No. 8 and began to throw sticks of wood at his door and rocks at his window. One cadet, Walter B. Guion, even shot through the door.

The Eggnog Riot was out of control. But it was about to get worse.

Hitchcock eventually called for Major William J. Worth, the Commandant of Cadets, to quell the crazed students. But the students thought he’d actually called for backup from “bombardiers” — the despised regular artillery men stationed at West Point. This caused the cadets to go into a deeper frenzy.

By 6:00 am Christmas morning, however, Worth had arrived on the scene. And by the time the reveille sounded at 6:05 a.m., the Eggnog Riot was over, though the North Barracks were in shambles. Cadets had smashed windows, torn off banisters, and destroyed plates and cups. Many of them were deeply hungover, if not still drunk, their uniforms in total disarray.

And Sylvanus Thayer had decide what to do about it.

West Point Cadets Face A Court Martial

Public DomainAn illustration of cadet life at West Point circa 1890s, decades after the Eggnog Riot.

The Eggnog Riot had left over $5,000 in damages at West Point. The school suffered broken windows, damaged stair banisters, and shattered dishware strewn about. And it had hardly been confined to one room — of the 260 cadets at West Point, 90 had been involved with the Eggnog Riot at one point or another. That meant that a full third of them could face expulsion, which was not a good look for the United States’ premier military academy.

Instead of handing down a blanket punishment, West Point conducted an inquiry into the event in January 1827. One hundred and sixty-seven witnesses were called to testify — including a cadet named Robert E. Lee who had not participated in the riot — and the investigation led to court-martial proceedings against 19 cadets and one soldier.

In the end, 19 cadets were found guilty and expelled from West Point. However, eight were granted clemency and five were allowed to graduate from West Point.

In the following years, West Point demolished the original buildings, instead opting for new designs that would make it harder for cadets to move from floor to floor. To this day, West Point maintains limited holiday celebrations — ensuring that the chaos of the Eggnog Riot remains a thing of the past.

After reading about the eggnog riot, dive into the true story of the Christmas Truce of 1914, when British and German troops celebrated together during World War One. Then, view 44 images of Christmas celebrations during the height of World War Two.