Notorious for her drunken exploits and various stints at mental health facilities, Frances Farmer was subjected to a slew of dark rumors — but here’s the truth about her story.

In early mid-century America, few movie stars were as famous as Frances Farmer. From 1936 to 1958, the actress appeared in 15 films alongside stars like Bing Crosby and Cary Grant, and she was known as much for her tumultuous private life as she was for her roles.

At the height of her career, Farmer was notoriously institutionalized, where legend had it that the star was lobotomized. Though her family later disputed this claim, the rumor spawned a slew of books and movies that focused on the gruesome surgery.

Indeed, despite her star-studded career, Farmer’s mental health struggles became the center of her legacy in a society obsessed with sensationalism. This is the true story of Frances Farmer, the actress whose battle with depression became an urban legend.

How Frances Farmer Got Her Start

FlickrA headshot of Frances Farmer for Paramount Pictures.

Born on September 19, 1913, in Seattle, Washington, Frances Farmer remembered having an unsteady childhood. After her parents divorced when she was four, Farmer moved to California with her mother only to be returned to her father in Seattle when her mother decided she couldn’t both work and care for her children efficiently.

Farmer later said that “being shunted from one household to another was a new adjustment, a fresh confusion, and I groped for ways to compensate for the disorder.” She did so by writing. When she was a senior in high school, she won a prestigious writing award for an essay she titled “God Dies.”

Her love of writing brought her to college where she studied journalism at the University of Washington before finding her true path in theater. She starred in numerous university plays, and by 1935, made the fateful decision to move to New York in order to jumpstart her career as a stage actress.

FlickrA glamorous Farmer.

She ended up signing a seven-year contract with Paramount Pictures instead and began appearing in B-movie comedy films. In 1936, however, she starred alongside Bing Crosby in a western titled Rhythm on the Range, turning her into a star almost overnight.

A noted homebody at this time, Paramount studio head Adolph Zukor phoned her and told her, “Now that she was a rising star she’d have to start acting like one.” But Farmer remained behind the scenes, and she still wanted to be taken seriously as an actress.

She thus traveled to upstate New York to participate in summer stock, where she caught the attention of playwright and director Clifford Odets. He offered her a part in his play, Golden Boy, which garnered her national praise. Farmer continued to work in the theater, spending only a few months out of the year in Los Angeles making movies.

In 1942, however, Farmer’s life began to fall apart.

Her Tumultuous Off-Screen Life

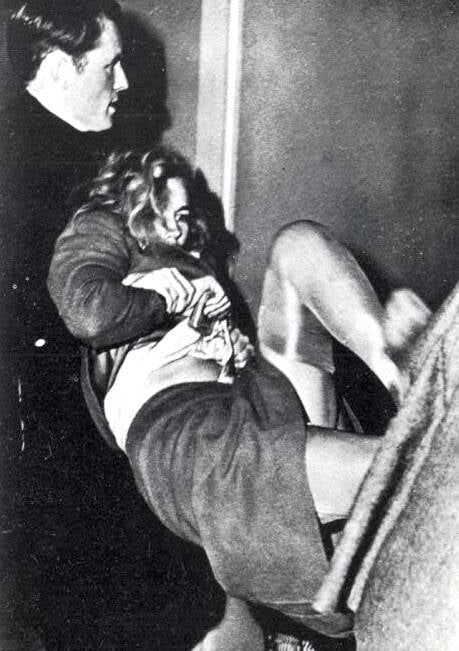

Wikimedia CommonsFarmer being restrained during a court hearing in 1943.

In June, Frances Farmer and her first husband — a Paramount actor she met shortly after signing her contract — divorced. Next, after refusing to take a role in Take A Letter, Darling, Paramount suspended her contract.

On October 19 of that year, Farmer was arrested for driving drunk with the car’s headlights on during a wartime blackout. Police fined her $500, and the judge forbade her from drinking. But Farmer still hadn’t paid the rest of her fine by 1943, and on January 6, a judge issued a warrant for her arrest.

On January 14, police tracked her down at the Knickerbocker Hotel, where she had been sleeping naked and drunk, and forced her to surrender to police custody. According to the Evening Independent, Farmer admitted she had been drinking “everything I could get my hands on, including Benzedrine.” The judge sentenced her to 180 days in jail.

Newspapers captured the gritty details of Farmer’s behavior, writing that she “floored a matron, bruised an officer, and suffered some rufflement on her own part” when police refused to let her use a telephone after her sentencing.

Matrons then purportedly had to remove Farmer’s shoes as they carried her off to her cell in order to prevent injury as she kicked at them. Farmer’s sister-in-law, who was present at the sentencing, decided that admitting Farmer to a psychiatric hospital would be preferable to imprisonment. Thus Farmer was transferred to California’s Kimball Sanitarium, where she spent nine months.

Farmer’s mother then traveled to Los Angeles, where a judge awarded her guardianship over Farmer. The two returned to Seattle, but things didn’t get much better for Farmer there. On March 24, 1944, Farmer’s mother checked her into Western State hospital yet again.

Though Farmer was released three months later, her freedom proved to be short-lived.

Claims Of Lobotomy And Abuse In The Hospital

Getty ImagesFarmer in a jail cell in 1943.

In May 1945, Frances Farmer returned to the hospital, and though she was paroled briefly in 1946, she would ultimately remain institutionalized at Western State Hospital for almost five more years.

It was during this stretch that rumors of a lobotomy were spawned. Popularized by claims in author William Arnold’s 1978 book on Farmer, Shadowland, the lobotomy rumor would become Farmer’s most enduring legacy, though it is factually flawed.

Indeed, in a 1983 court case over copyright infringement related to the book’s film adaptation, Arnold admitted that he made the lobotomy story up, and the presiding judge ruled that “portions of the book were fabricated by Arnold from whole cloth despite the subsequent release of the book as nonfiction.”

Additionally, Farmer’s sister Edith Elliot wrote her own account of her famous sibling’s life in the self-published book, Look Back In Love.

In it, Elliot wrote that their father visited Western State Hospital in 1947, just in time to stop the lobotomy from occurring. According to Elliot, he wrote that “if they tried any of their guinea pig operations on her, they would have a danged big lawsuit on their hands.”

That’s not to say that Frances Farmer suffered no abuse at the hospital, however. In her posthumously published autobiography, Will There Really Be A Morning?, Farmer wrote that she was “raped by orderlies, gnawed on by rats and poisoned by tainted food … chained in padded cells, strapped into strait jackets and half drowned in ice baths.”

But even knowing the truth of Farmer’s own account of her life is difficult. For one thing, Farmer didn’t finish the book, it was her close friend, Jean Ratcliffe, who did. And it could very well have been the case that Ratcliffe embellished parts of the book to fulfill the requirements of the publisher, who had given Farmer a large advance before her death.

Indeed, a 1983 newspaper claimed that Ratcliffe intentionally made the story more dramatic in hopes of securing a movie deal. Whatever the truth was of her time in the hospital, on March 25, 1950, Farmer was released — this time for good.

Frances Farmer Wrestles Back Control Of Her Life

vintag.esA 1940 publicity shot of Farmer.

Believing that her mother might institutionalize her again, Farmer moved to have her guardianship removed. In 1953, a judge agreed that she could indeed take care of herself, and legally restored her competency.

After her parents’ deaths, Farmer moved to Eureka, California, where she became a bookkeeper. She connected with television executive Leland Mikesell there, whom she would eventually marry and later divorce, and who convinced her to return to television.

In 1957, Farmer moved to San Francisco with the help of Mikesell and began her comeback tour. She appeared on The Ed Sullivan Show, later telling one newspaper that she had finally “come out of all this a stronger person. I won the fight to control myself.”

Still intent on becoming a stage actress, Frances Farmer returned to the theater and even made another movie. An opportunity to continue working in the theater took her to Indianapolis, where an NBC affiliate asked her to host a daily series that showcased vintage films, and she accepted.

In a 1962 letter to her sister, Farmer penned that she had “enjoyed the last few weeks so much in quiet and settled way, and I do think I’ve never felt better in my life.” But Farmer still struggled with alcohol abuse, and after a couple of DUI citations and a drunk on-camera appearance, Farmer was fired.

Not to be deterred, Farmer kept acting, this time taking several roles in productions at Purdue University, where she served as actress-in-residence. In her autobiography, Farmer recalls those Purdue productions as some of the best and most fulfilling work of her career:

“[T]here was a long silent pause as I stood there, followed by the most thunderous applause of my career. [The audience] swept the scandal under the rug with their ovation … my finest and final performance. I knew I would never need to act onstage again.”

And she largely never did. In 1970, Farmer was diagnosed with esophageal cancer and died in August of that year at the age of 57.

Her story, equal parts true despair and devastating myth, would endure. Indeed, Frances Farmer’s life would inspire the works of countless artists to come, whose own struggles in some ways resembled those of Hollywood’s fallen angel.

If you were intrigued by the story of Frances Farmer, then check out these vintage Hollywood photos. Or, read about the true story behind the shocking Lizzie Borden murders.