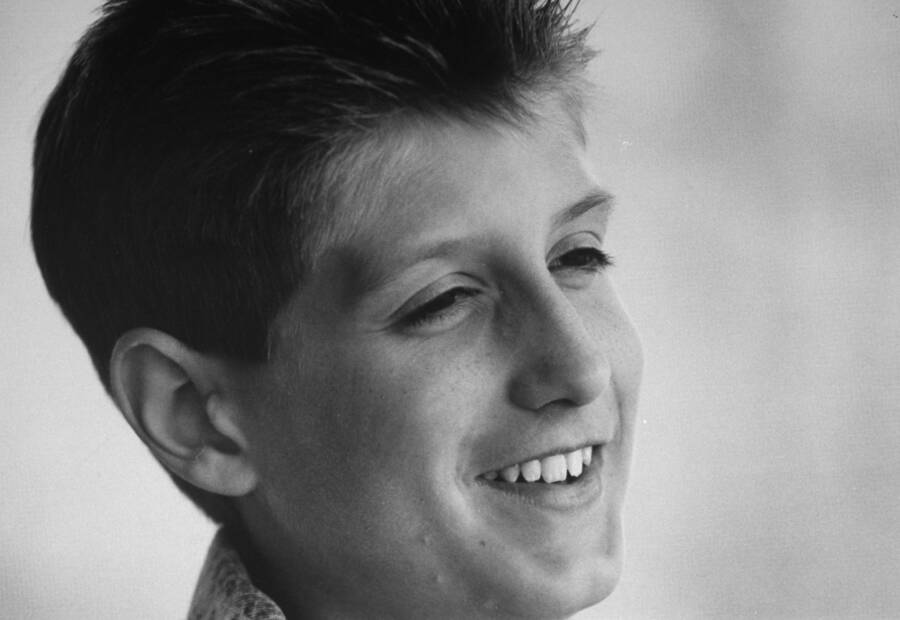

After Ryan Wayne White of Kokomo, Indiana was diagnosed with AIDS on December 17, 1984, his case sparked widespread discussion about this stigmatized disease.

Taro Yamasaki/The LIFE Images Collection/Getty ImagesAfter Ryan White was diagnosed with AIDS in 1984, parents and teachers in his hometown of Kokomo, Indiana tried to prevent him from returning to school.

In the 1980s, a mysterious new disease called Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS) caused by the newly discovered human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) swept America. With a fatality rate nearing 100%, the epidemic’s lethal combined with the public’s lack of understanding of how HIV was transmitted led to nationwide panic. In Kokomo, Indiana, that panic was turned against a teenager with hemophilia named Ryan White, who quickly became a social pariah after testing positive.

But instead of retreating from the limelight, Ryan White became the poster child for the AIDS epidemic and the misunderstandings surrounding it. He spent the remaining years of his life as a public advocate for AIDS awareness and help end the stigma around the disease before ultimately dying of it himself on April 8, 1990.

The 1980s AIDS Epidemic And The Panic It Inspired

When scientists diagnosed the first case of AIDS in 1981, no one had any idea that it would become a raging epidemic — or how awful it would be.

The public responded to the epidemic as they tend to do with something like this: widespread panic and hysteria. Politicians pushed to quarantine people with HIV and California put an AIDS-quarantine initiative on the ballot.

In the New York Times, the famous public intellectual and conservative political writer William F. Buckley suggested that “everyone detected with AIDS should be tattooed.”

Paul Chinn/Los Angeles Public LibraryThousands attended a 1983 rally in Los Angeles in support of more funding for AIDS research.

As scientists tried to identify how HIV spread, the public targeted two groups who were believed to be particularly vulnerable to HIV infections: homosexuals and drug users. Religious leaders like Reverend Jerry Falwell declared that AIDS was a punishment sent by God to kill homosexuals and junkies — and he was not alone in that sentiment.

Those with HIV were presumed to have done something to deserve it and people believed that they shouldn’t be allowed to spread the disease to those who didn’t, even if it meant punishing sick children like Ryan White.

Who Was Ryan White?

Born Ryan Wayne White on December 6, 1971, White had just turned 13 years old when doctors diagnosed him with AIDS in December 1984. White, then living in Kokomo, Indiana, was one of the first children ever diagnosed with the condition, and his prognosis was very poor — his doctors gave him only six months to live.

Ryan’s mother, Jeanne White Ginder, remembers thinking, “How could he have AIDS?”

White had hemophilia, a genetic blood disorder inhibits blood clotting that can make even the most insignificant wounds deadly. Unlike in earlier decades, where internal bleeding caused by hemophilia was often fatal, by the 1970s and 1980s, patients with hemophilia were saved by a miracle treatment known as Factor VIII.

By injecting Factor VIII into a hemophilia patient’s bloodstream, doctors could treat any internal bleeding issues and save the lives of their hemophiliac patients.

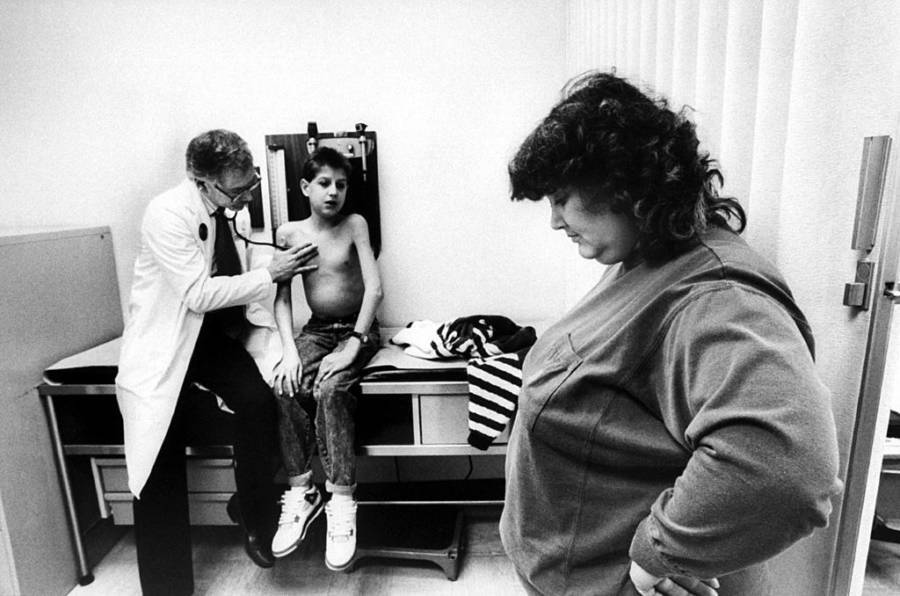

Taro Yamasaki/The LIFE Images Collection/Getty ImagesRyan White at the doctor’s office with his mother, Jeanne White Ginder.

The problem was that scientists had been isolating Factor VIII from pooled blood donations taken from countless anonymous donors, but in the 1980s there was still no way to screen these donated blood for HIV. As a consequence, thousands of doses of Factor VIII were unknowingly contaminated with HIV.

So when doctors gave White one of these doses to treat his hemophilia sometime in the late 1970s or early 1980s, they infected the young boy with HIV — a guaranteed death sentence in 1984. “Virtually every hemophiliac I treated in the mid-1980s has since died from AIDS,” said Dr. Howard Markel, director of the Center for the History of Medicine at the University of Michigan.

How Ryan White’s Community Turned On Him

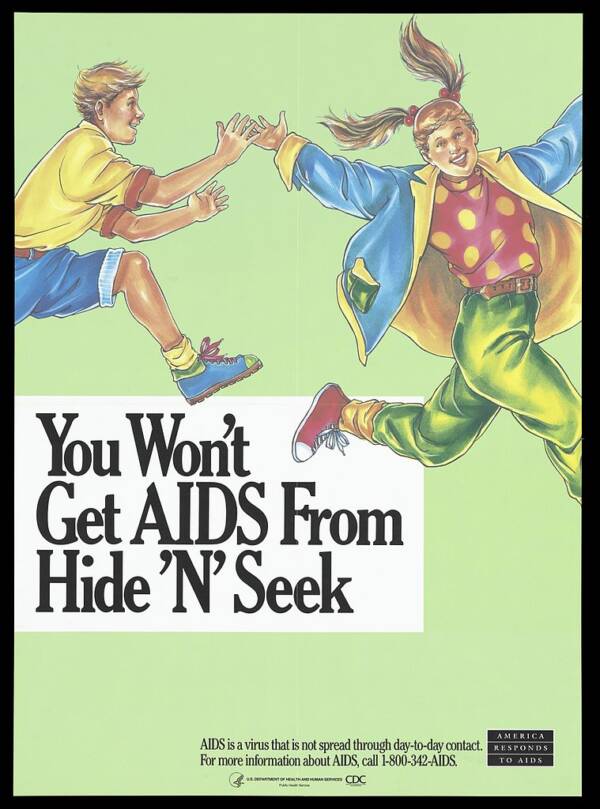

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services/Wellcome LibraryPublic health posters educated Americans on AIDS.

After his diagnosis in 1984, Ryan White’s doctors gave him six months to live. But, after overcoming a serious illness, White said he wanted to return to school. Ginder remembers her son telling her, “I want to go to school, I want to go visit my friends. I want to see my friends.”

But his school, Western Middle School, would not let him return; parents and teachers worried that White would infect other students with HIV. With public education about the virus nonexistent, fears were rampant that sharing a bathroom or even just a handshake with someone infected with HIV could spread the disease. Parents even began pulling their kids out of the school in protest.

These protests moved the superintendent of the district to block White from returning. Instead, the teenager was forced to use a telephone to listen in on his seventh-grade classes from home.

The Whites successfully sued the school, drawing national attention to Ryan’s experience.

But when Ryan finally returned to school, his fellow students vandalized his locker and bullied him, often throwing homophobic insults at him. Outside of school, the family endured slashed car tires and rocks thrown through their windows.

“It was really bad,” Ginder later said. “People were really cruel, people said that he had to be gay, that he had to have done something bad or wrong, or he wouldn’t have had it.”

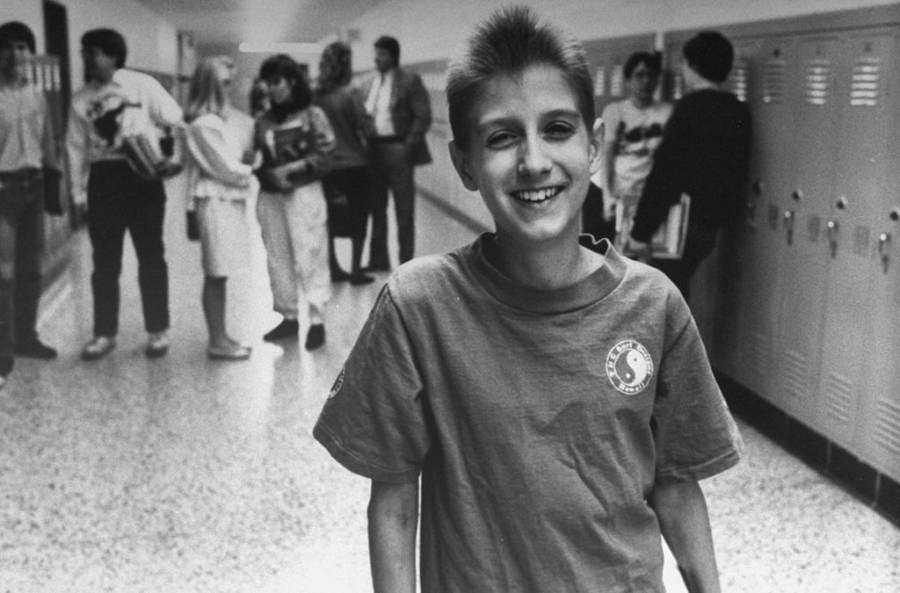

In 1987, the White family was forced to move twenty miles away to Cicero, Indiana. Ginder remembers gratefully how the town welcomed their family and how, on his first day at Hamilton Heights High School, the principal, Tony Cook, welcomed Ryan White personally — with a handshake.

“Ryan hardened my commitment for allowing him to experience school without limitation upon my first meeting with him and his mother, Jeanne,” Cook said.

Brad Letsinger, a Hamilton Heights student in the late 1980s, said that it wasn’t easy at first, but that White soon found his place at the school.

“When he first came, a lot of people were really scared,” Letsinger said. “But Ryan helped all of us to understand. He didn’t want people to feel sorry for him. He hated that. He just wanted to be a regular kid.”

Taro Yamasaki/The LIFE Images Collection/Getty ImagesRyan White in the hallway of his school.

As a high schooler, Ryan White even got a summer job at a skateboard shop and when his mom asked if the $3.50 an hour he made at the shop would even cover the cost of gas, her son replied, “Mom, you don’t get it. I got a job just like everyone else does.”

White’s Heroic Activism For AIDS Awareness And Education

During the height of the AIDS epidemic, Ryan White became one of its most important spokesmen, advocating and educating the nation about the disease. Journalists flocked to Indiana to learn more about White’s experience and he used this media attention to fight back against the stigma that people had attached to people with AIDS.

Thomas Brandt, spokesman for the National Commission on AIDS in 1990, said, “After seeing a person like Ryan White – such a fine and loving and gentle person – it was hard for people to justify discrimination against people who suffer from this terrible disease.”

More importantly, White’s case led the CDC in 1985 to begin screening blood and blood products for the HIV antibody to prevent transmission through blood transfusions.

In 1989, The Ryan White Story premiered on broadcast television, bring even more attention to the cause of those with HIV/AIDS. He even attended the Academy Awards in 1990.

White was still very sick, however, and he soon began to decline until, on April 8, 1990, he succumbed to the disease and passed away in Indianapolis. He was just one month away from graduating from High School.

Taro Yamasaki/The LIFE Images Collection/Getty ImagesAIDS Ryan White lying covered up in his bed, chatting with his mom Jeanne in his room at home.

Indiana flew flags at half staff in Ryan’s honor, and President George H.W. Bush declared, “Ryan’s death reaffirms that we as a people must pledge to continue the fight, his fight against this dreaded disease.”

Four months after his death, Congress passed the Ryan White Comprehensive AIDS Resources Emergency Act. Today, more than half of HIV-positive Americans receive services through the Ryan White HIV/AIDS program and his advocacy led to increased funding for research into a treatment for the disease.

He may have lost his life far too young, but as a result of his efforts with the time he had left, he ensured that countless others would live lives that had been tragically denied to him and many others during the AIDS epidemic.

After reading the story of Ryan White, learn about activist David Kirby who also helped change the way Americans saw the deadly disease. Then, check out these historic photos of the AIDS epidemic.