"Feral Child" Genie Wiley was strapped to a chair by her parents and neglected for 13 years before she was finally rescued — then she was experimented upon by researchers studying human development.

Getty ImagesFor the first 13 years of her life, Genie Wiley suffered unimaginable abuse and neglect at the hands of her parents.

The story of Genie Wiley the Feral Child sounds like the stuff of fairytales: An unwanted, mistreated child survives brutal imprisonment at the hands of a savage ogre and is rediscovered and reintroduced to the world in an impossibly youthful state. Unfortunately for Wiley, hers is a dark, real-life tale with no happy ending. There would be no fairy godmothers, no magic solutions, and no enchanted transformations.

Genie Wiley was separated from any form of socialization and society for the first 13 years of her life. Her intensely abusive father and helpless mother so neglected Wiley that she hadn’t learned to speak and her growth was so stunted that she looked like she was no more than eight years old.

Her intense trauma proved something of a godsend to scientists of various fields including psychology and linguistics, though they were later accused of exploiting the child for their research on learning and development. But Genie Wiley’s case did beg the question: What does it mean to be human?

This is the haunting story of Genie Wiley.

The Horrifying Upbringing That Turned Genie Wiley Into A “Feral Child”

Genie isn’t the Feral Child’s real name. She was given the name to protect her identity once she became a spectacle of scientific research and awe.

ApolloEight Genesis/YouTubeThe home in which Genie Wiley was raised by her abusive parents.

Susan Wiley was born in 1957 to Clark Wiley and his much-younger wife Irene Oglesby. Oglesby was a Dust Bowl refugee who had drifted to the Los Angeles area where she met her husband. He was a former assembly-line machinist raised in and out of brothels by his mother. This childhood had a profound effect on Clark, as for the rest of his life he’d fixate on the figure of his mother.

Clark Wiley never wanted children. He hated the noise and stress they brought along. Nonetheless, the first baby girl did come along and Wiley left the child in the garage to freeze to death when she wouldn’t be quiet.

The Wiley’s second baby died of a congenital defect, and then came along Genie Wiley and her brother John. While her brother also faced their father’s abuse, it was nothing compared to Susan’s suffering.

Though he was always a bit off, the death of Clark Wiley’s mother by a drunk driver in 1958 seemed to undo him completely. The end to the complicated relationship they shared fanned his cruelty into a bonfire.

ApolloEight Genesis/YouTubeGenie Wiley’s mother was legally blind, which was supposedly the reason why she felt she couldn’t intervene on her daughter’s behalf during the abuse.

Clark Wiley decided that his daughter was mentally disabled and that she’d be useless to society. Thus, he banished society from her. No one was allowed to interact with the girl who was mostly locked in a blacked-out room or in a makeshift cage. He kept her strapped into a toddler toilet as a sort of straight-jacket, and she wasn’t potty-trained.

Clark Wiley would hit her with a large plank of wood for any infraction. He’d growl outside her door like a deranged guard dog, instilling a lifelong fear of clawed animals in the girl. Some experts believe sexual abuse may have been involved, due to Wiley’s later sexually inappropriate behavior, particularly involving older men.

In her own words, Genie Wiley, the Feral Child recalled:

“Father hit arm. Big wood. Genie cry… Not spit. Father. Hit face — spit. Father hit big stick. Father is angry. Father hit Genie big stick. Father take piece wood hit. Cry. Father make me cry.”

She had spent 13 years living this way.

Genie Wiley’s Salvation From Torment

Genie Wiley’s mother was nearly blind which she later said kept her from interceding on her daughter’s behalf. But one day, 14 years after Genie Wiley’s first introduction to her father’s cruelty, her mother did finally muster her courage and leave.

In 1970, she stumbled into social services, mistaking it for the office where they’d give aid to the blind. The office workers’ antennae were immediately raised when they noticed the young girl acting so strangely, hopping like a bunny instead of walking.

Genie Wiley was then nearly 14 but she looked no more than eight.

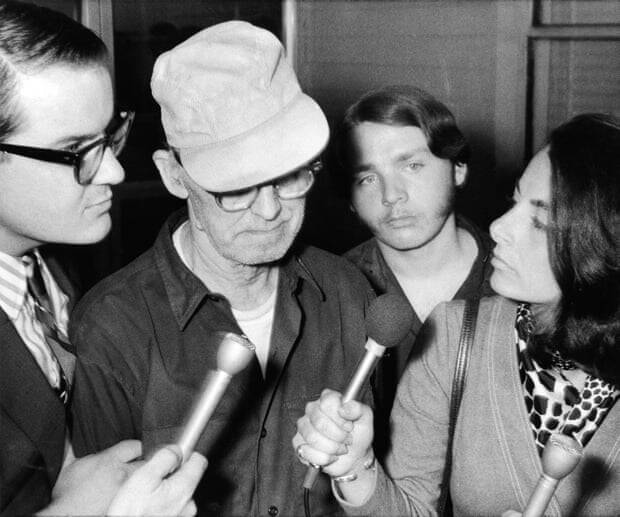

Associated PressClark Wiley (center left) and John Wiley (center right) after the abuse scandal broke open.

An abuse case was immediately opened against both parents, but Clark Wiley would kill himself shortly before trial. He left behind a note which read: “The world will never understand.”

Wiley became a ward of the state. She knew but a few words when she entered UCLA’s Children’s Hospital and was dubbed by medical professionals there as “the most profoundly damaged child they had ever seen.”

Wiley’s case soon enchanted scientists and physicians who applied for and were rewarded a grant by the National Institute of Mental Health to study her. The team explored the “Developmental Consequence of Extreme Social Isolation” for four years from 1971 to 1975.

For those four years, Genie Wiley became the center of these scientists’ lives. “She wasn’t socialized, and her behavior was distasteful,” began Susie Curtiss, a linguist intimately involved in the feral child study, “but she just captivated us with her beauty.”

But also for those four years, Wiley’s case tested the ethics of a relationship between a subject and their researcher. Genie Wiley would come to live with many of the team members who observed her which was not only a huge conflict of interest but also potentially begat another abusive relationship in her life.

Researchers Begin Experimenting On The “Feral Child”

ApolloEight Genesis/YouTubeFor four years, Genie the Feral Child was subject to scientific experimentation that some felt was too intense to be ethical.

Genie Wiley’s discovery timed precisely with an uptick in the scientific study of language. To language scientists, Wiley was a blank slate, a way to understand what part language has in our development and vice versa. In a twist of dramatic irony, Genie Wiley now became deeply wanted.

One of the foremost tasks of the “Genie Team” was to establish which came first: Wiley’s abuse or her lapse in development. Did Wiley’s developmental delay come as a symptom of her abuse, or was Wiley born challenged?

Up until the late 1960s, it was largely believed by linguists that children could not learn language after puberty. But Genie the Feral Child disproved this. She had a thirst for learning and curiosity and her researchers found her “highly communicative.” It turned out that Wiley could learn language, but grammar and sentence structure was another thing entirely.

“She was smart,” Curtiss said. “She could hold a set of pictures so they told a story. She could create all sorts of complex structures from sticks. She had other signs of intelligence. The lights were on.”

Genie Wiley showed that grammar becomes inexplicable to children without training between five and 10, but communication and language remains entirely attainable. Wiley’s case also posed some more existential questions about the human experience.

“Does language make us human? That’s a tough question,” said Curtiss. “It’s possible to know very little language and still be fully human, to love, form relationships and engage with the world. Genie definitely engaged with the world. She could draw in ways you would know exactly what she was communicating.”

TLCSusan Curtiss, a UCLA linguistics professor, helps Genie the Feral Child to find her voice.

As such, Wiley could construct simple phrases to convey what she wanted or was thinking, like “applesauce buy store,” but the nuances of a more sophisticated sentence structure were out of her grasp. This demonstrated that language is different from thought.

Curtiss explained that “For many of us, our thoughts are verbally encoded. For Genie Wiley, her thoughts were virtually never verbally encoded, but there are many ways to think.”

Genie the Feral Child’s case did help to establish that there is a point beyond which total language fluency is impossible if the subject does not already speak one language fluently.

According to Psychology Today:

“The case of Genie confirms that there is a certain window of opportunity that sets the limit for when you can become relatively fluent in a language. Of course, if you already are fluent in another language, the brain is already primed for language acquisition and you may well succeed in becoming fluent in a second or third language. If you have no experience with grammar, however, Broca’s area remains relatively hard to change: you cannot learn grammatical language production later on in life.”

Continued Exploitation Of Genie Wiley

For all their contributions to understanding human nature, the “Genie Team” was not without its critics. For one thing, each of the scientists on the team accused each other of abusing their position and relationships with Genie Wiley the feral child.

For instance, in 1971, language teacher Jean Butler obtained permission to bring Wiley home with her for socialization purposes. Butler was able to contribute some integral insights on Wiley in this environment, including the feral child’s fascination with collecting buckets and other containers that stored liquid, a common trait amongst other children who have faced extreme isolation. She also saw that Genie Wiley was beginning puberty at this time, a sign that her health was strengthening.

The arrangement went along well enough for a time until Butler claimed she caught Rubella and would need to quarantine herself and Wiley. Their temporary situation turned more permanent. Butler turned away the other physicians on the “Genie Team” claiming that they were subjecting her to too much scrutiny. She applied for the foster care of Wiley as well.

Later, Butler was accused by other members of the team of exploiting Wiley. They said Butler believed her young ward would make her “the next Anne Sullivan,” the teacher who helped Helen Keller to become more than invalid.

As such, Genie Wiley later went to live with the family of therapist David Rigler, another member of the “Genie Team.” As far as Genie Wiley’s luck would allow, this seemed to be a good fit for her and a time to develop and discover the world with people who genuinely cared for her well-being.

The arrangement also gave the “Genie Team” more access to her. As Curtiss later wrote in her book Genie: A Psycholinguistic Study of a Modern-Day Wild Child:

“One particularly striking memory of those early months was an absolutely wonderful man who was a butcher, and he never asked her name, he never asked anything about her. They just connected and communicated somehow. And every time we came in — and I know this was so with others, as well — He would slide open the little window and hand her something that wasn’t wrapped, a bone of some sort, some meat, fish, whatever. And he would allow her to do her thing with it, and to do her thing, what her thing was, basically, was to explore it tactilely, to put it up against her lips and feel it with her lips and touch it, almost as if she were blind.”

Wiley remained an expert in non-verbal communication and had a way of expressing her thoughts to people even if she couldn’t speak to them.

Rigler, too, recalled how one time a father and his young son carrying a fire engine passed by Genie Wiley. “And they just passed,” Rigler remembered. “And then they turned around and came back, and the boy, without a word, handed the fire engine to Genie. She never asked for it. She never said a word. She did this kind of thing, somehow, to people.”

Despite the progress she displayed at the Riglers’, once the funding ended for the study in 1975, Wiley went to live with her mother for a brief period. In 1979, her mother filed a lawsuit against the hospital and her daughter’s individual caregivers, including the scientists on the “Genie Team,” alleging they exploited Wiley for “prestige and profit.” The suit was settled in 1984 and Wiley’s contact with her researchers all but entirely severed.

Wikimedia CommonsGenie Wiley was returned to foster care after the research on her ended. She regressed in these environments and never regained speech.

Wiley was eventually placed in a number of foster homes, some of which were also abusive. There Wiley was beaten for vomiting and regressed greatly. She never regained the progress she had made.

Genie Wiley Today

Genie Wiley’s present life is little-known; once her mother took custody, she refused to let her daughter be the subject of any more studies. Like so many people with special needs, she fell through the cracks of proper care.

Wiley’s mother died in 2003, her brother John in 2011, and her niece Pamela in 2012. Russ Rymer, a journalist, tried to piece together what led to the dissolution of Wiley’s team, but he found the task challenging as the scientists had all divided on who was exploitative and who had the feral child’s best interests in mind. “The tremendous rift complicated my reporting,” Rymer said. “That was also part of the breakdown that turned her treatment into such a tragedy.”

He later recalled visiting Susan Wiley on her 27th birthday and seeing:

“A large, bumbling woman with a facial expression of cowlike incomprehension… her eyes focus poorly on the cake. Her dark hair has been hacked off raggedly at the top of her forehead, giving her the aspect of an asylum inmate.”

Despite this, Genie Wiley is not forgotten by those that cared about her.

“I’m pretty sure she’s still alive because I’ve asked each time I called and they told me she’s well,” Curtiss said. “They never let me have any contact with her. I’ve become powerless in my attempts to visit her or write to her. I think my last contact was in the early 1980s.”

Curtiss added in a 2008 interview that she has “spent the last 20 years looking for her… I can get as far as the social worker in charge of her case, but I can’t get any farther.”

As of 2008, Wiley was in an assisted living facility in Los Angeles.

Genie Wiley’s story is not a happy one as she drifted from one abusive situation to another, and by all accounts, was denied and failed by society at every step. But, one can hope that wherever she is, she continues to find joy in discovering the still-new world around her, and instills in others the fascination and affection that she had for her researchers.

After this look at Genie Wiley the Feral Child, read about teenage murderer Zachary Davis and Louise Turpin, the woman who kept her children captive for decades.