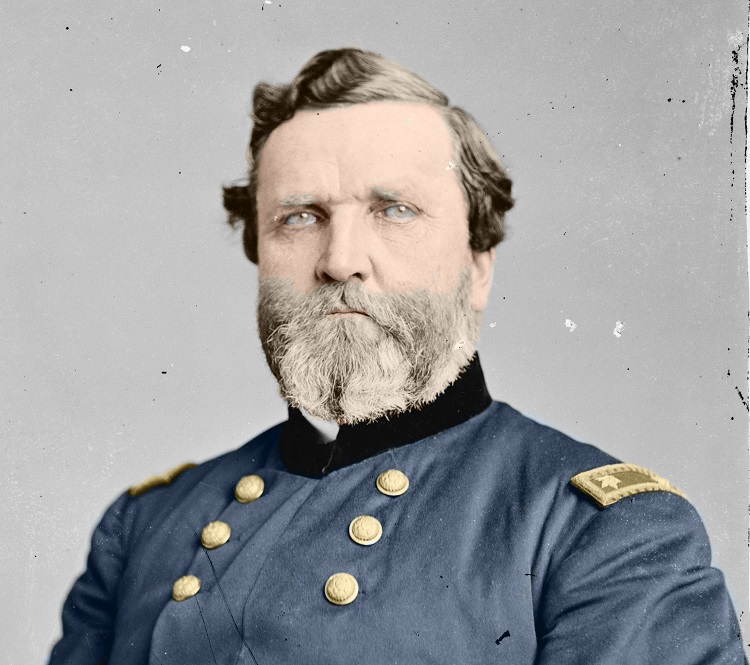

Despite his many Union victories in the American Civil War, George Henry Thomas is hardly a household name.

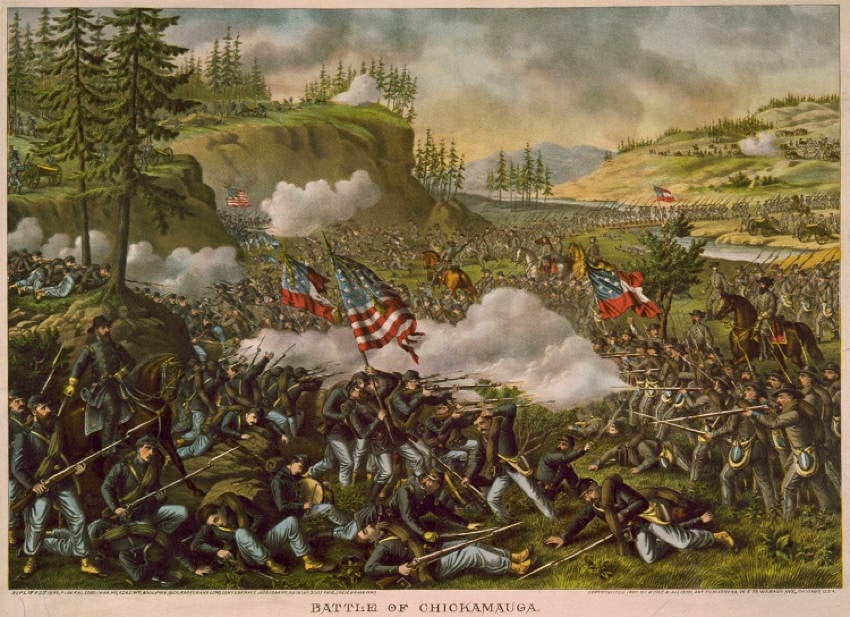

Source: Civil War Talk

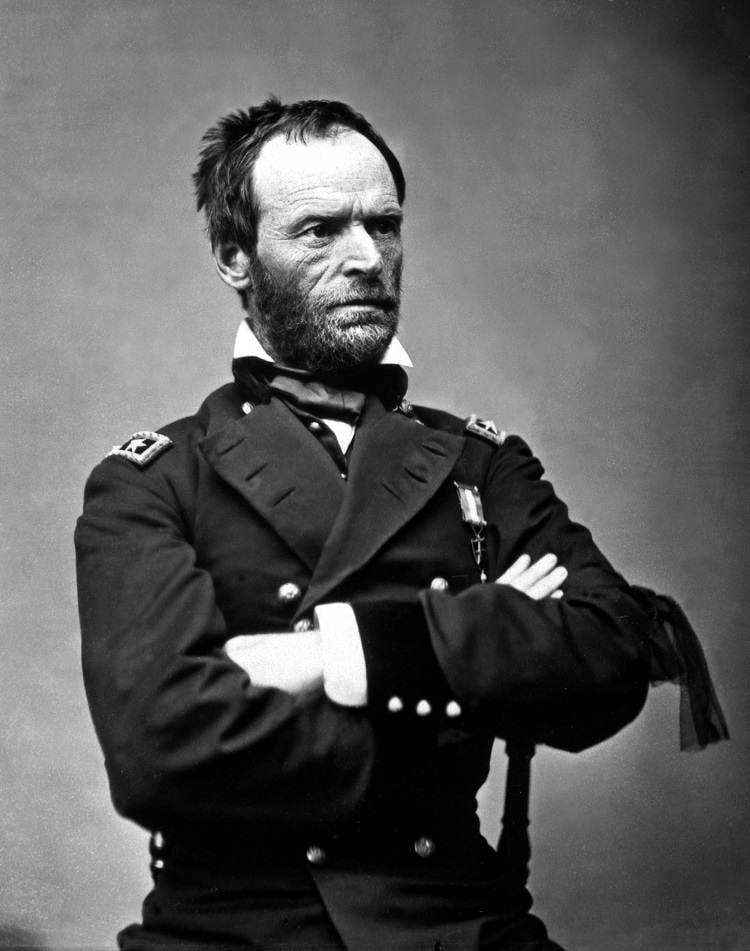

By many accounts George Henry Thomas was one of the greatest military minds in American history. So why isn’t his name mentioned in the same breath as Ulysses S. Grant, Robert E. Lee, George McArthur or George Patton? Thomas graduated in the same West Point class as William Tecumseh Sherman, and commanded over some triumphant victories that bested his former classmate. But even during the Civil War, politics determined who advanced in the ranks, and Thomas had one handicap that he couldn’t change: he was a Southerner fighting for the Union.

As a professional soldier, George Henry Thomas’ loyalty was with the U.S. Army that he served so faithfully. But the decision to turn down a position in the Confederate army was an agonizing one, according to his wife Frances Kellogg Thomas, who was a staunch Unionist, which may have further influenced her husband’s decision.

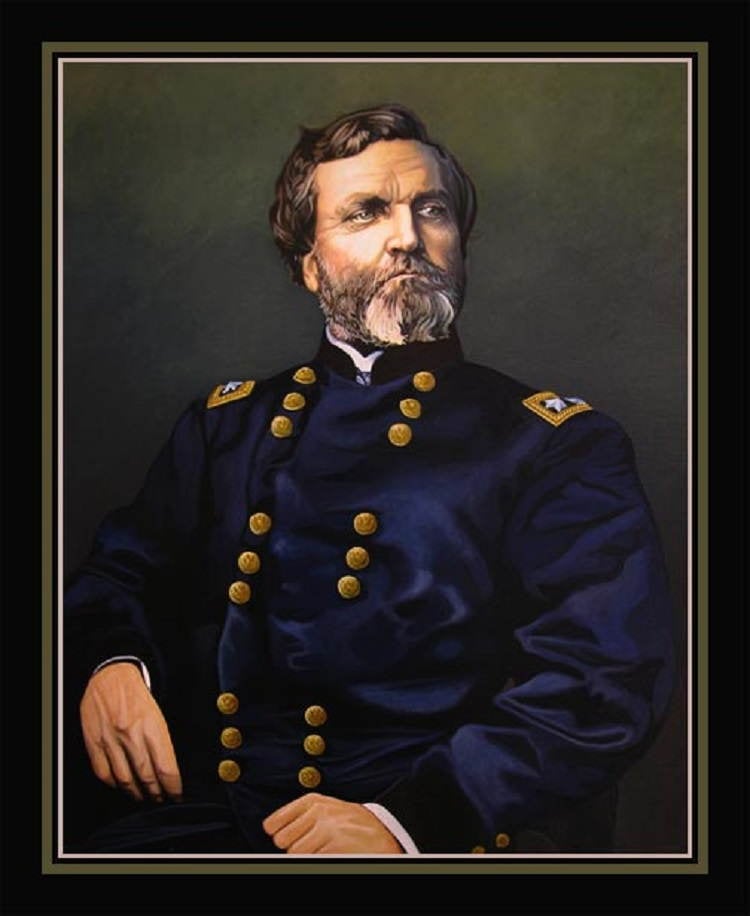

Source: Civil War Artist

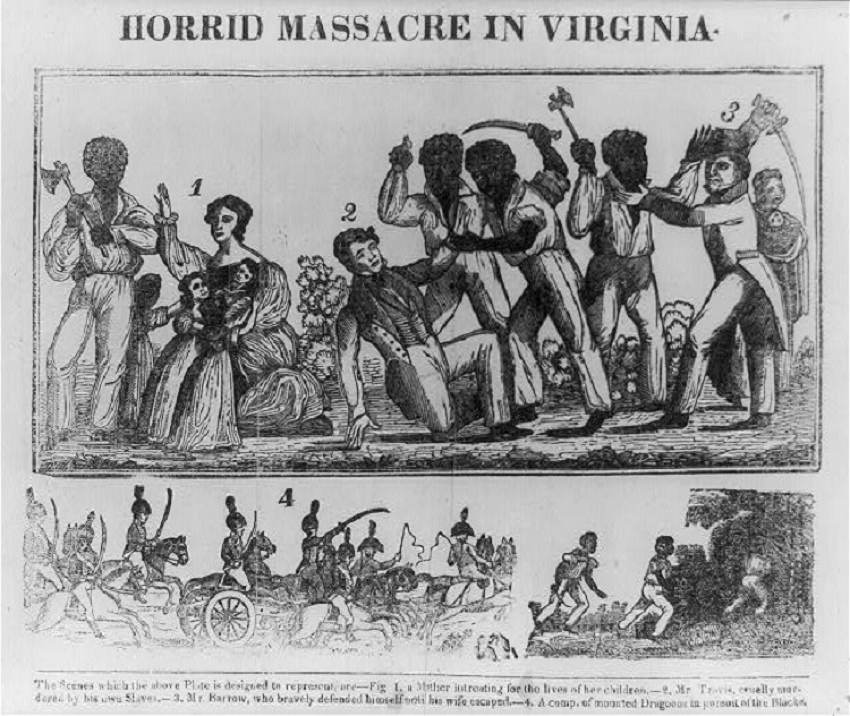

Source: Blogspot

Bred and born in Virginia, Thomas’ family narrowly survived the Nat Turner uprising in Southampton County. Thomas was 15. He would soon become a lifelong soldier, entering West Point when he was not yet 20. Upon graduating, he first became acquainted with war under Andrew Jackson in battles against the Seminole Indians.

In fact, Thomas served on the field under three future presidents, Jackson, Zachary Taylor in the Mexican-American War and Grant; and his contemporaries included future president James Garfield. Thomas was himself considered for the presidency long after the Civil War, but he quashed any consideration early on, not wanting the job. Such factors have colluded to keep his name obscure in the country’s history.

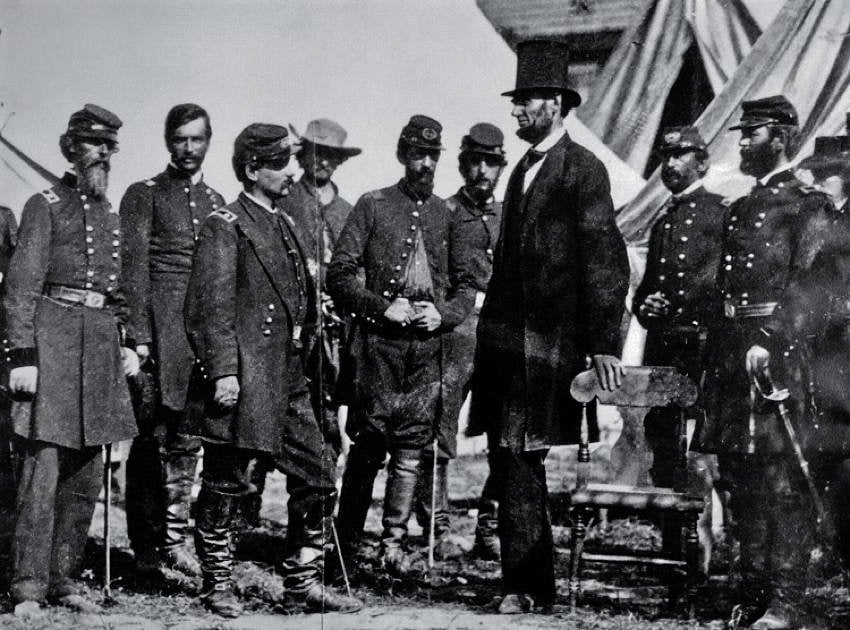

Source: Blogspot

But renewed interest in old battles of the Civil War leading up to the current sesquicentennial have caused writers and historians to reexamine Thomas’ contributions to the epic fight and his sacrifices on the battlefield and in his personal life. When Thomas decided to fight for the Union, he was disowned by his family for the remainder of his life and labeled a traitor by the rest of the South.

The decision to fight on the side of the North may also have prevented advancement is his career. Thomas eventually became a major general for the Union, but even Lincoln was leery of making a commander out of a Southerner who had served under Lee before the war, according to author Ernest B. Furguson.

Source: Michael Hyatt

Smithsonian Magazine calls Thomas “The Forgotten General,” even though he is credited with many of the great Union victories in the Civil War. In one of the first notable Northern successes in the strife, then-brigadier general Thomas and his outnumbered men claimed victory in Kentucky when they drove Confederates across the Cumberland River and back into Tennessee.

Leading a group of General William Rosecrans’ men, he did the same at Stones River and Missionary Ridge during the Tullahoma campaign in Tennessee, battles that some historians call a turning point for the war.

Source: Wikimedia

When all seemed lost at the battle of Chickamauga Creek and his commanding general and five other generals retreated, George Henry Thomas dug in with his men and led them to safety after nightfall. The feat earned him the nickname of “Rock of Chickamauga.” Finally, he took control of the Army of the Cumberland and held the all-important cities of Chattanooga and Nashville, driving Rebels from their nests.

Thomas was an important figure in the war’s Western Theater. As historian Bruce Catton would note: “…just twice in all the war was a major Confederate army driven away from a prepared position in complete rout—at Chattanooga and at Nashville. Each time the blow that finally routed it was launched by Thomas.”

Source: Wikimedia

Source: Son Of The South

Yet George Henry Thomas rarely received credit for his military prowess, with the glory going instead to men who served under him. Burguson has another explanation for the snubbing, besides Thomas’ Southern heritage: His old West Point roommate Sherman and Grant were jealous of his conquests and refused to recognize them.

They criticized his thoroughness as being too slow. And when Grant became general in chief of all Union armies, it was Sherman who was promoted to commander in the West, despite Thomas’ considerable accomplishments in the region and the fact that he out-ranked Sherman.

When the struggle was over and the war extinguished, Thomas didn’t even get to be part of the raucous Union victory celebrations and parades in Washington, D.C. Instead, he said goodbye to his troops in the west. After Lincoln’s assassination, the overlooked general continued to command troops in Kentucky, Tennessee, Mississippi, Alabama and Georgia. But when President Andrew Johnson finally offered to make him lieutenant general, Thomas, a bit old and perhaps over it at this point, declined the offer. He died of a stroke in 1870 at the age of 53.

Source: Wikimedia

We will never know how Thomas felt about being passed up for promotions time and time again because most of his personal papers were destroyed. When Thomas died, Grant, who had ascended to the presidency and his old rival Sherman, who had become General in Chief, led the mourners and eventually showered praise on their fallen comrade, with Grant calling Thomas “one of the greatest heroes of our war.”

Toward the end of the 19th century he was honored with an image on $5 U.S. bank notes and there is a statue of him in Washington’s Thomas Circle, but it pales in comparison to Grant’s Tomb. Despite his heroic performance and the devotion of his men, in his own time, George Henry Thomas was never given his due. But he might finally be getting it today.