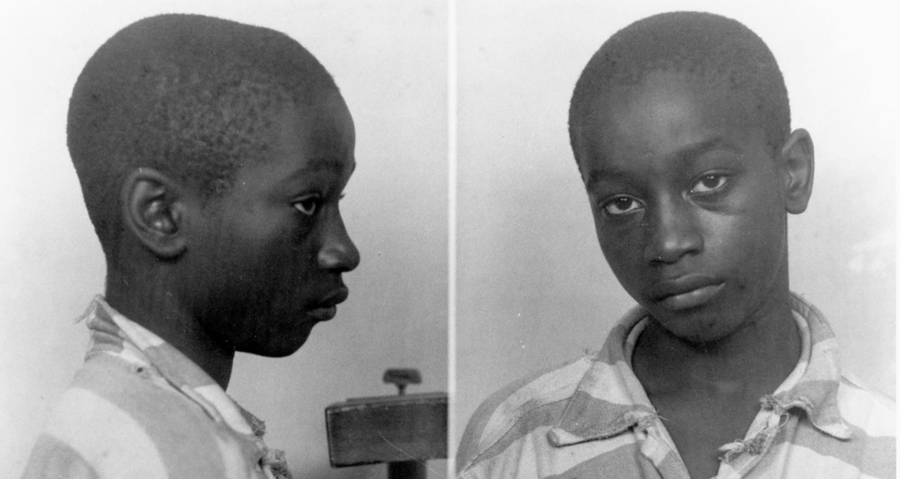

George Stinney Jr. was just 14 years old when he was executed in South Carolina in 1944. It took 10 minutes to convict him — and 70 years to exonerate him.

The youngest person in the United States to ever be put to death in the electric chair was an African-American 14-year-old named George Stinney Jr. He was executed in the Deep South in 1944, in the midst of the Jim Crow era.

George Stinney Jr. lived in the segregated mill town of Alcolu, South Carolina, where white people and black people were separated by railroad tracks. Stinney’s family lived in a humble company house — until they were forced to leave when the young boy was accused of killing two white girls.

South Carolina Department of Archives and HistoryGeorge Stinney Jr. was just 14 years old when he was executed in 1944.

It took a jury of white men 10 minutes to find Stinney guilty — and it would take 70 years before Stinney was exonerated.

The Murder Of Betty June Binnicker And Mary Emma Thames

On March 23, 1944, 11-year-old Betty June Binnicker and 7-year-old Mary Emma Thames were riding their bicycles in Alcolu looking for flowers. When they saw George Stinney and his younger sister Aime during their journey, they stopped and asked if they knew where to find maypops, the yellow edible fruit of passionflowers.

That was reportedly the last time the girls were seen alive.

File/Reuters Mary Emma Thames (left) is pictured with her family in 1943. Thames and her friend Betty June Binnicker were murdered the following year.

Binnicker and Thames, who were white, never made it home that day. Their disappearance prompted hundreds of Alcolu residents, including Stinney’s father, to come together and search for the missing girls. It wasn’t until the next day when their dead bodies were discovered in a soggy ditch.

When Dr. Asbury Cecil Bozard examined their bodies, there was no clear sign of a struggle, but both girls had met violent deaths involving multiple head injuries.

Thames had a hole boring straight through her forehead into her skull, along with a two-inch-long cut above her right eyebrow. Meanwhile, Binnicker had suffered at least seven blows to the head. It was later noted that the back of her skull was “nothing but a mass of crushed bones.”

Bozard concluded that Binnicker and Thames had wounds that were likely caused by a “round instrument about the size of the head of a hammer.”

A rumor floated around town that the girls had made a stop at a prominent white family’s home on the same day of their murder, but this was never confirmed. And police certainly didn’t seem to be looking for a white killer.

When Clarendon County law enforcement officers learned from a witness that Binnicker and Thames were seen talking to Stinney, they went to his home. There, George Stinney Jr. was promptly handcuffed and interrogated for hours in a small room without his parents, an attorney, or any witnesses.

A Two-Hour Trial

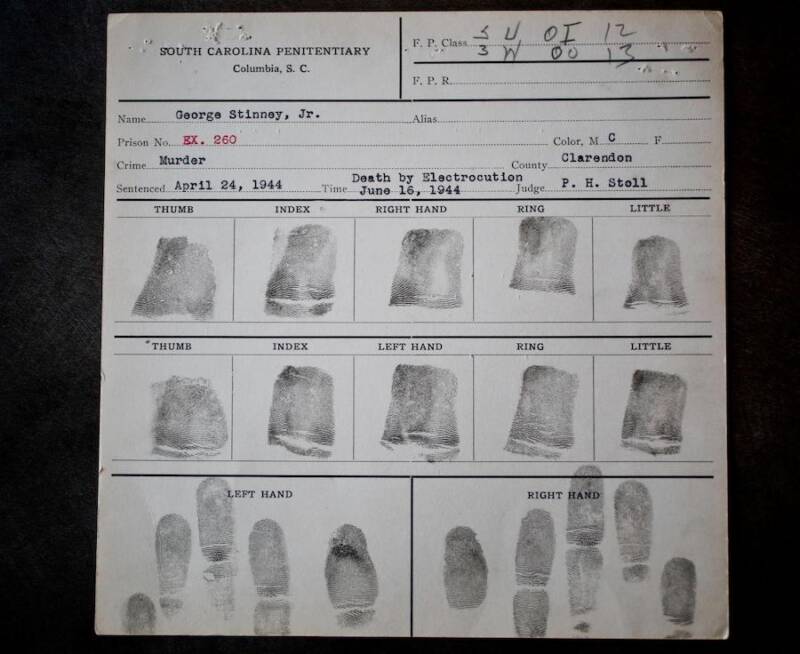

South Carolina Department of Archives and HistoryGeorge Stinney Jr.’s fingerprints are pictured on this certificate.

Police claimed that George Stinney Jr. confessed to murdering Binnicker and Thames after his plan to have sex with one of the girls failed.

An officer named H.S. Newman wrote in a handwritten statement, “I arrested a boy by the name of George Stinney. He then made a confession and told me where to find a piece of iron about 15 inches long. He said he put it in a ditch about six feet from the bicycle.”

Newman refused to reveal where Stinney was detained, as rumors of lynching spread throughout the town. Not even his parents knew where he was as his trial quickly approached. At the time, 14 was considered the age of responsibility — and Stinney was believed to be responsible for murder.

About a month after the girls’ deaths, George Stinney Jr.’s trial began at a Clarendon County Courthouse. Court-appointed attorney Charles Plowden did “little to nothing” to defend his client.

During the two-hour trial, Plowden failed to call witnesses to the stand or present any evidence that would cast doubt on the prosecution’s case. The most significant piece of evidence presented against Stinney was his alleged confession, but there was no written record of the teenager admitting to the murders.

By the time of his trial, Stinney hadn’t seen his parents in weeks, and they were too afraid of getting attacked by a white mob to come to the courthouse. So the 14-year-old was surrounded by strangers — up to 1,500 of them.

Following a deliberation that took less than 10 minutes, the all-white jury found Stinney guilty of murder, with no recommendation for mercy.

On April 24, 1944, the 14-year-old was sentenced to die by electrocution.

The Execution Of George Stinney Jr.

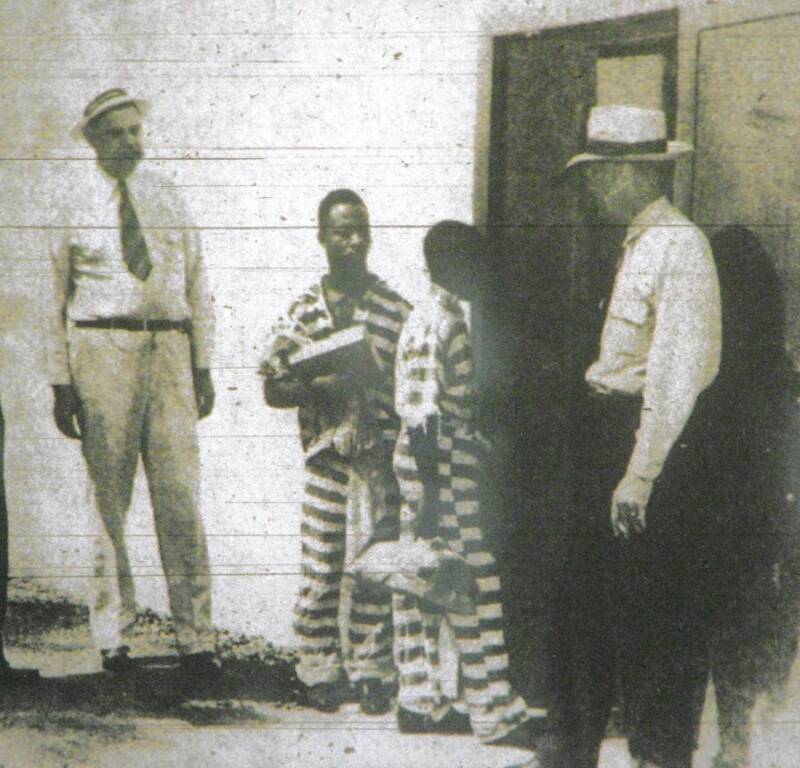

Jimmy Price/Columbia RecordGeorge Stinney Jr. (second from right) was likely coerced into confessing to the murder of two girls.

George Stinney Jr.’s execution was not without protest. In South Carolina, organizers for both white and black ministerial unions petitioned Gov. Olin Johnston to grant Stinney clemency based on his young age.

Meanwhile, hundreds of letters and telegrams poured into the governor’s office, begging him to show mercy to Stinney. Stinney’s supporters appealed with everything from the basic idea of fairness to the concept of Christian justice.

But in the end, none of it was enough to save George Stinney.

On June 16, 1944, George Stinney Jr. walked into the execution chamber at the South Carolina State Penitentiary in Columbia with a Bible tucked under his arm.

Weighing in at just 95 pounds, he was dressed in a loose-fitting striped jumpsuit. Strapped into an adult-size electric chair, he was so small that the state electrician struggled to adjust an electrode to his right leg. A mask that was too big for him was placed over his face.

An assistant captain asked Stinney if he had any last words. Stinney replied, “No sir.” The prison doctor prodded, “You don’t want to say anything about what you did?” Again, Stinney replied, “No sir.”

When officials turned on the switch, 2,400 volts surged through Stinney’s body, causing the mask to slip off. His eyes were wide and teary, and saliva was emanating from his mouth for all the witnesses in the room to see. After two more jolts of electricity, it was over.

Stinney was pronounced dead shortly thereafter. In a span of just 83 days, the boy had been charged with murder, tried, convicted, and executed by the state.

A Murder Conviction Overturned 70 Years Later

Tribune News Service via Getty Images Katherine Robinson, one of George Stinney’s sisters, testifies to what she remembers from the day of his arrest. The 70-year-old case of George Stinney Jr. was re-examined in 2014.

George Stinney’s murder conviction was thrown out in 2014. His siblings claimed that his confession was coerced and that he had an alibi: At the time of the murders, he was with his sister Aime watching the family’s cow.

They also noted that a man named Wilford “Johnny” Hunter, who claimed to be Stinney’s cellmate, said that Stinney denied murdering Binnicker and Thames.

“He said, ‘Johnny, I didn’t, didn’t do it,'” Hunter said. “He said, ‘Why would they kill me for something I didn’t do?'”

After months of consideration, on December 17, 2014, Judge Carmen T. Mullen vacated the murder conviction, calling George Stinney Jr.’s death sentence a “great and fundamental injustice.”

George Stinney Jr.’s siblings were overjoyed to learn that their brother was exonerated after 70 years, appreciating that they were able to live long enough to see it happen.

“It was like a cloud just moved away,” said Stinney’s sister, Katherine Robinson. “When we got the news, we were sitting with friends… I threw my hands up and said, ‘Thank you, Jesus!’ Someone had to be listening. It’s what we wanted for all these years.”

After reading about George Stinney Jr., relive the civil rights movement in 55 powerful photos. Then, view the harrowing images of the Tulsa race riots.