Tired of racism in Missouri, George Washington Bush decided to explore the American frontier. And in 1844, he became the first Black man to settle in Washington Territory.

In 1844, a group of American pioneers headed west out of Missouri. Like the countless others who ventured west, they hoped for a better life on the American frontier. But unlike most frontiersmen, this group included one unusual member: a free Black man named George Washington Bush.

Henderson House MuseumNo one knows exactly what George Washington Bush looked like — this sketch is from 1969.

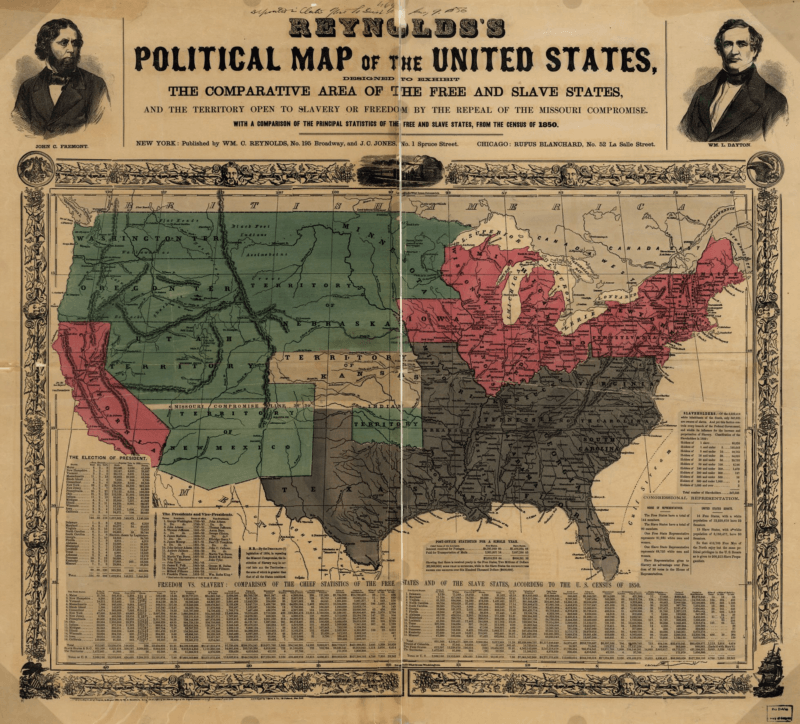

Seventeen years before the Civil War, free Black people were rare in the United States, making up just 1.5 percent of the total population. But Bush was not only free — he had helped to fund the entire trip.

This is the remarkable story of the man widely recognized as the first Black pioneer to settle the Pacific Northwest.

George Washington Bush’s Struggles With Racism

George Washington Bush (some historians believe that Washington was not his middle name, however) was an unusual man for his time. By the time he was born around 1790, the newly-formed United States had almost 700,000 slaves, yet Bush was born free — and to interracial parents. This was 150 years before interracial marriage would even be legal across the entire U.S.

His mother was an Irish-American maid and his father was either a sailor of African descent or from India.

Despite the racism that pervaded America, Bush lived his early years in Pennsylvania like many other young men in America. He fought in the U.S. Army, explored the nation as a fur trader, and made money raising cattle. In 1830, he married a white woman named Isabella James and settled in Missouri to raise their nine sons.

But because of his skin color, George Washington Bush was tormented by racism — especially in the years leading up to the Civil War. By 1844, this prompted him to move even farther West.

Library of CongressA map of the United States from 1856 showing free states, slave states, and territories.

“As far as I know, he was having a hard time in Missouri,” said one of his descendants, Emma Belle Bush, discussing his move West. “People would not sell him anything because they said he was a Negro.”

One of George Washington Bush’s contemporaries, the pioneer Ezra Meeker, seconded this. “George Bush doubtless left Missouri because of the virulent prejudices against his race.”

So it was that in May 1844, Bush and his family joined a group of his friends and neighbors and headed toward the Oregon Territory. The party included four white families — and Bush helped pay for their wagons and supplies.

Exclusion From Oregon Territory

National California/Oregon Trail CenterA depiction of life on the Oregon Trail.

George Washington Bush and the pioneers were hopeful for a fresh start in the Oregon Territory. But Bush nevertheless worried that racism wouldn’t be so easy to outrun.

“He told me he should watch, when we got to Oregon, what usage was awarded to people of color,” recalled John Minto, a member of Bush’s party. “If he could not have a free man’s rights he would seek the protection of the Mexican government in California or New Mexico.”

Bush’s fears were not unfounded.

A few months before he and his party arrived in Oregon, the Oregon provisional government adopted the Black Exclusion Law — which made it illegal for Black people to settle there. Anyone who dared defy the law would be whipped 39 times, in public, every six months until they left the Oregon Territory.

The five families on the trail made a decision. If one of them couldn’t settle in Oregon, then none of them would.

Instead, they went north. Bush and the others settled along the Deschutes River, where he established his new home on Bush Prairie in what is now the state of Washington.

George Washington Bush’s Legacy In Washington State To This Day

Washington State Historical SocietyBush Prairie, the Bush family homestead, in 1909.

As an early settler in the Pacific Northwest, George Washington Bush built a reputation as a kind and caring man.

He got along with both the Indigenous Americans living in the area — Bush even learned their language — and with new settlers. During hard times, he didn’t hesitate to share what he had.

“[Bush] divided out nearly his whole crop to new settlers who came with or without money,” said Meeker. “He became a benefactor to the whole community.”

In turn, the community took care of Bush. When it seemed that he might lose the claim to his land — because a new law said only whites could own land — his neighbors petitioned the Washington Territory legislature to exempt Bush. The legislature agreed.

He passed his exemplary nature on to his children. In 1889, his eldest son, William, became the first African American to serve in the Washington legislature.

When George Washington Bush died on April 5, 1863, he left behind a powerful legacy for those who knew him. However, his memory faded in the following years as stories of white pioneers took precedence.

But today, a new monument has been planned for Washington State’s capitol building in hopes of rectifying his memory.

“To have [Bush] and his family recognized at the state level in this way is huge,” said Stephanie Johnson-Toliver, president of the Black Heritage Society of Washington State.

His monument will be near a butternut tree from Missouri which Bush planted when he first came West in search of a better life.

After learning about George Washington Bush, check out these 48 incredible photos of the American frontier. Then, learn about the Black cowboys who settled the West.