Georgia Tann ran the Memphis branch of the Tennessee Children's Home Society, where she matched over 5,000 kids with adoptive parents between 1924 and 1950 — but her work was anything but virtuous.

The Commercial Appeal/ZUMApress.com / Alamy Stock PhotoGeorgia Tann meeting with prospective adoptive parents at the Tennessee Children’s Home Society in 1939.

Starting in the 1920s, Georgia Tann ran the Tennessee Children’s Home Society in Memphis — but her work was anything but charitable. In fact, many of the babies she placed in homes around the country weren’t orphans at all: She’d kidnapped them.

Since Tennessee law only allowed the Society to charge $7 for in-state adoptions, Tann found families in New York and California who would pay up to $5,000 for an infant. It was no problem for Tann if newborns were in short supply. She would simply coerce a poor, single mother to hand over her baby. And if Tann got desperate, she would take the child under the guise of providing medical care and then tell its family that it had died.

This horrific scheme continued for 26 years. Tann sold an estimated 5,000 children during this time, including wrestling icon Ric Flair and the twin daughters of actress Joan Crawford. And she never saw justice.

Three days before authorities announced charges against the Tennessee Children’s Home Society in 1950, Georgia Tann died from uterine cancer. Although she escaped personal prosecution, her actions sparked adoption reform laws meant to ensure that nobody could ever carry out such disturbing crimes again.

Georgia Tann’s Early Life And Move To Memphis

Georgia Tann was born in rural Mississippi in 1891. Her father, who was a judge, had big dreams for her. He hoped that she would become a professional pianist, and although young Georgia went along with the lessons he paid for, she disliked playing. She did earn a degree in music from Martha Washington College in Virginia in 1913, but her true interests were in the legal field.

Tann wanted to become a lawyer like her father, so she asked him to tutor her and successfully passed the Mississippi state bar exam. Female lawyers were almost unheard of at the time, though, so Tann turned to a different career: social work. She had already taken a few summer courses at Columbia University, and she secured a job at the Mississippi Children’s Home Society.

Public DomainGeorgia Tann in 1947, three years before the Tennessee Children’s Home Society was investigated for selling children.

While working as a receiving director, she met housemother Ann Atwood. The two of them became close friends — and their relationship may have eventually turned romantic. During this time, Tann also adopted a baby girl named June Ann.

After just a couple of years on the job, Tann was fired for inappropriate child-placing methods in 1924. She and Atwood moved to Memphis, where Tann found another position as the executive secretary at the Tennessee Children’s Home Society. It was there that she started her disturbing scheme that would continue for decades and harm thousands of families.

The Black Market At The Tennessee Children’s Home Society

Although Tennessee law prevented adoption agencies from charging families who lived in the state more than $7 for a child, Georgia Tann quickly found a way to circumvent these rules and make extra money. She discovered that she could charge a premium for out-of-state adoptions, as wealthy parents in New York and California were willing to spend thousands for infants.

Tann would charge these families for background checks that she rarely ran, inflated travel costs, and paperwork that cost pennies compared to what she listed on the invoice. With this method, she brought in up to $5,000 per child, pocketing more than 80 percent of the money herself in a secret bank account under a fake company name. She also failed to report her earnings to the IRS.

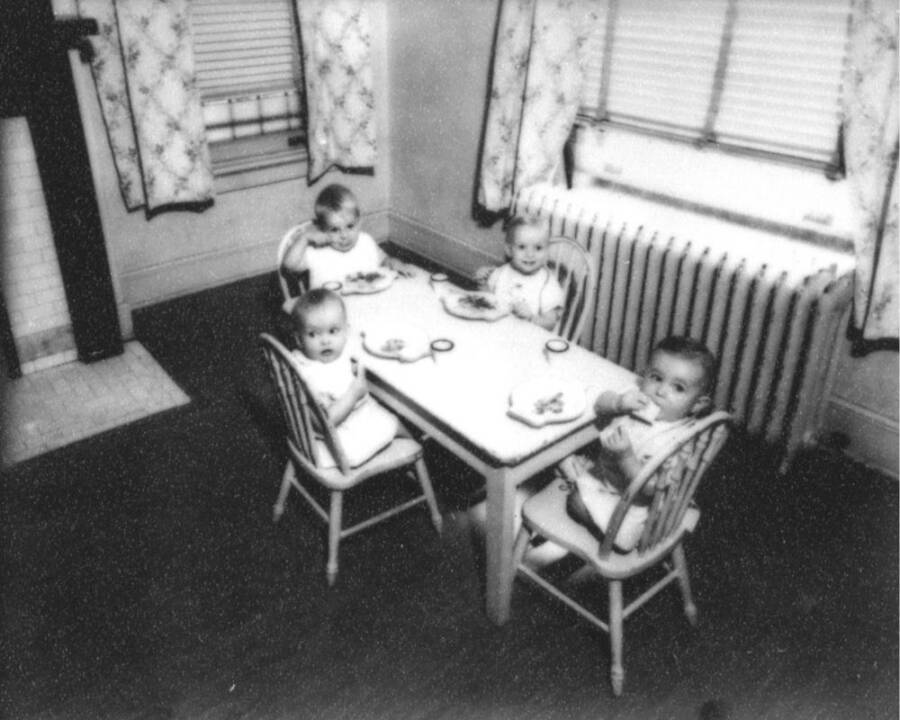

Memphis Public LibrariesToddlers eating at the Tennessee Children’s Home Society in 1949.

Georgia Tann believed that children should be taken from low-income families and placed with “people of the higher type.” She used high-pressure tactics to take infants from single mothers, convincing them that the babies would be better off in her care. She targeted homes for unwed mothers as well as mental institutions, stealing newborns from inmates soon after birth.

Some of her more heartbreaking strategies involved explicit lies. Tann would reportedly tell poor mothers who were still in the hospital that their infant needed medical attention. She would then sell the baby and say that it had died. Tann also promised families going through hard times that she would care for their children until they were back on their feet — and then say that she had no record of the kids when their parents came back for them.

Barbara Bisantz Raymond, who wrote a book about Tann’s career, told the Memphis Commercial Appeal in 2007, “She was completely organized. She was always scanning newspapers, always looking for children to take. If it was mentioned that a woman died and had left children, she would show up. She ran ads that said ‘Young Women in Trouble Call Miss Georgia Tann.'”

Special Collections Department/University of MemphisThe building that housed the Tennessee Children’s Home Society.

“She bribed nurses and paid people off,” said Raymond. “She worked through manipulation and intimidation. Deputy sheriffs went to the homes of poor people and hauled off babies and children.”

Tann’s clientele included celebrities like Joan Crawford, who adopted twins from the Tennessee Children’s Home Society in 1947, as well as actors Dick Powell and June Allyson. Wrestling legend Ric Flair was one of the roughly 5,000 children Tann adopted out during her career.

And not all of these children had happy endings.

Bringing Down Georgia Tann’s Criminal Enterprise

Georgia Tann didn’t seem to care who she placed children with, as long as she got her money. Some went to abusive families — and others never made it out of the Tennessee Children’s Home Society at all. Many infants died from malnutrition in Tann’s care, as she frequently ignored doctors’ advice about sick babies.

Memphis Public LibrariesCribs filled with infants at the Tennessee Children’s Home Society nursery.

Theresa Jennings was adopted from the Society as a newborn. Her parents visited the agency to meet a baby boy and went home with her instead. She told the Commercial Appeal in 2018, “[M]y father kept hearing this noise and asked, ‘What is that?’ Georgia Tann said, ‘Oh, don’t worry about that,’ and kept talking about the baby boy. But my father was insistent, and so he and my mother walked to the crib where I lay. I was 13 days old. My tongue was literally tied to the bottom of my mouth, and I was covered in a scaly rash.”

Jennings’ adoptive parents took her to the doctor, who diagnosed her with a cow’s milk allergy. “I had been left there to die,” said Jennings.

These shocking practices continued until 1950. That year, Governor Gordon Browning of Tennessee received reports that the Tennessee Children’s Home Society was selling babies for a profit. He launched an investigation on Sept. 11 that revealed that Tann had allegedly brought in $1 million over the decades.

Charges were filed against the agency, but not before Georgia Tann died from uterine cancer on Sept. 15, 1950, at age 59.

Stinson Liles/Wikimedia CommonsA memorial for the children who died under the care of Georgia Tann.

Shelby County Family Court Judge Camille Kelley was accused of aiding Tann by ruling in her favor during cases to separate children from their mothers and place them in Tann’s custody. While she wasn’t officially charged, a report from the time found that Kelley had “failed on many occasions to aid destitute families and permitted family ties to be destroyed when they might well have been preserved.”

Georgia Tann’s crimes did help to change adoption legislation in Tennessee — but at the cost of countless babies’ lives. Today, a memorial to just a fraction of the children who died in Tann’s care stands at a cemetery in Memphis. It reads: “In the memory of the 19 children who finally rest here unmarked if not unknown, and of all the hundreds who died under the cold, hard hand of the Tennessee Children’s Home Society. Their final resting place unknown. Their final peace a blessing. The hard lesson of their fate changed adoption procedure and law nationwide.”

After learning about the crimes of Georgia Tann and the Tennessee Children’s Home Society, go inside the disturbing history of orphan trains. Then, look through these tragic photos of child laborers in the United States.