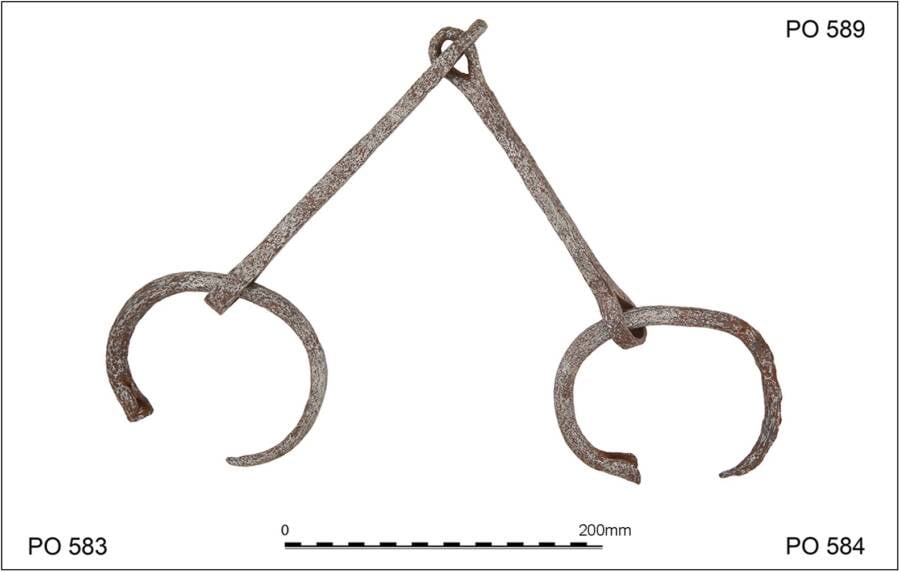

The iron shackles date back to the 3rd century B.C.E. — and they might help experts further understand slavery in Ptolemaic Egypt.

Bérangère Redon/French Archaeological Mission at the Eastern Desert; Antiquity Publications Ltd.The iron ankle shackles were discovered at the Ghozza mine in Egypt.

Two sets of iron shackles were found at the site of an ancient gold mine in Egypt, highlighting the human cost of gold mining in the Ptolemaic era. The shackles were discovered at Ghozza, the northernmost Ptolemaic gold mine, which operated during the 3rd century B.C.E.

Though researchers already knew that enslaved laborers were a driving force behind Egypt’s gold industry, this discovery from January 2023 confirms that some of the ancient workers at Ghozza specifically were victims of forced labor. Chillingly, some may have even been chained while they worked.

A study published in Antiquity this year goes into specific details about these shackles and what they may represent in the broader context of ancient Egypt’s gold mining operations — and the harsh conditions of the mines.

Iron Shackles Found At Ghozza Highlight A Dark Past For The Ptolemaic Mine

Bérangère Redon/French Archaeological Mission at the Eastern Desert; Antiquity Publications LtdA complete set of ankle shackles unearthed at the Ghozza mine.

Archaeologist Bérangère Redon led the excavation at the ancient site of Ghozza, during which two sets of ankle shackles were uncovered. They were found near ancient tools and fragments of pottery and provided the first real evidence that at least some workers at Ghozza were forced laborers.

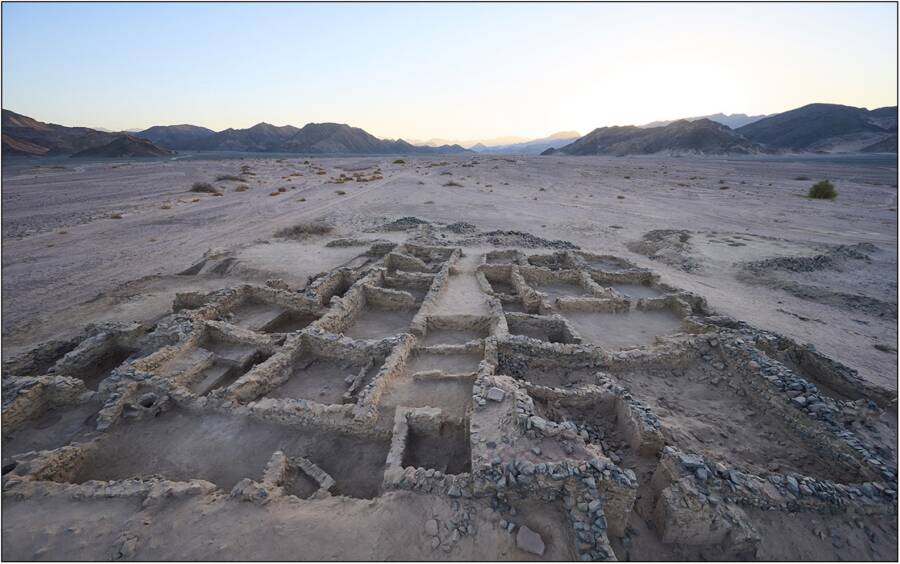

It has been well documented that other Ptolemaic gold mines used forced labor, but in most cases, there were structures like guarded dormitories that provided clear evidence of this practice at mines. At Ghozza, however, there were no such structures. Because of this, some researchers may have assumed that the Ghozza mine did not have enslaved laborers and that all of the workers there were paid, but the newly discovered shackles contradict this and expose the “harsh reality” of life at the mine.

“The discovery of shackles at Ghozza reveals that at least part of the workforce was composed of forced labour,” Redon wrote in the new study. “The exact living conditions of these individuals remain unclear because their dwelling places have not yet been identified, indeed the village set-up seems to suggest that the population was free to move around in general.”

M. Kačičnik, Institut français d’archéologie orientaleThe excavated Sector 44 at Ghozza.

Historical texts made mention of shackles and shackled workers — in particular, that prisoners of war and criminals were often subjected to this punishment under the Ptolemies — but actually finding shackles is a rarity, the study noted. Even more remarkably, the Ghozza shackles are among the oldest ever found in the Mediterranean region, pre-dating similar Late Iron Age and Roman-era shackles that had been uncovered across Europe.

In fact, they bear fascinating similarities to shackles found in Greek silver mines, suggesting there may have been some connection between Greek and Ptolemaic mines. In the study, Redon posited the theory that these shackles, and perhaps other technologies, were initially set up by Greek and Macedonian engineers, then brought to Egypt by the Ptolemies.

The Harsh Reality In Ptolemaic Gold Mines

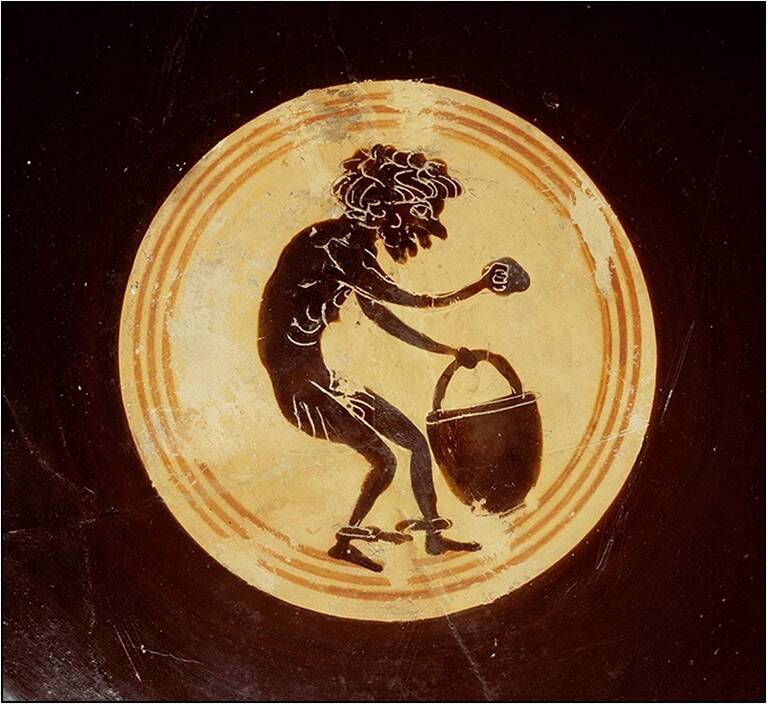

National Museum of Antiquities, Leiden, inv. K 1894/9.15An image of a shackled man found on a kylix in Naples.

While most ancient mines were riddled with harsh conditions, the Ptolemaic gold mines may have been especially cruel. To extract gold at Ghozza, workers used handheld grinding stones, a backbreaking process on its own that would be even more unbearable in the desert heat.

So far, no human remains have been found in relation to the shackles, but historical accounts indicated that many miners met a grim fate while working. The 2nd-century B.C.E. Greek historian Agatharchides once wrote of these mines: “And those who have been condemned in this way — and they are of a great multitude and all have their feet bound — work at their tasks unceasingly both by day and throughout the entire night.”

The gold extracted from these mines often went to funding the Ptolemies’ various military campaigns and the lavish lifestyles of the elites, but research suggests that the mines were not just used for economic reasons. Rather, experts believe the mines were part of a larger system of exploitation, a way to exert control over those deemed less worthy by ancient society.

“Beneath the grandeur of Egypt’s wealth and the imposing mountains of the Eastern Desert lies a history of exploitation,” Redon wrote. “The gold extracted from these mines helped finance the ambitions of Egypt’s rulers, but it came at a significant human cost.”

After reading about this discovery at an ancient Egyptian gold mine, learn about the truth behind who really built the Egyptian pyramids. Then, read about why so many Egyptian statues have broken noses.