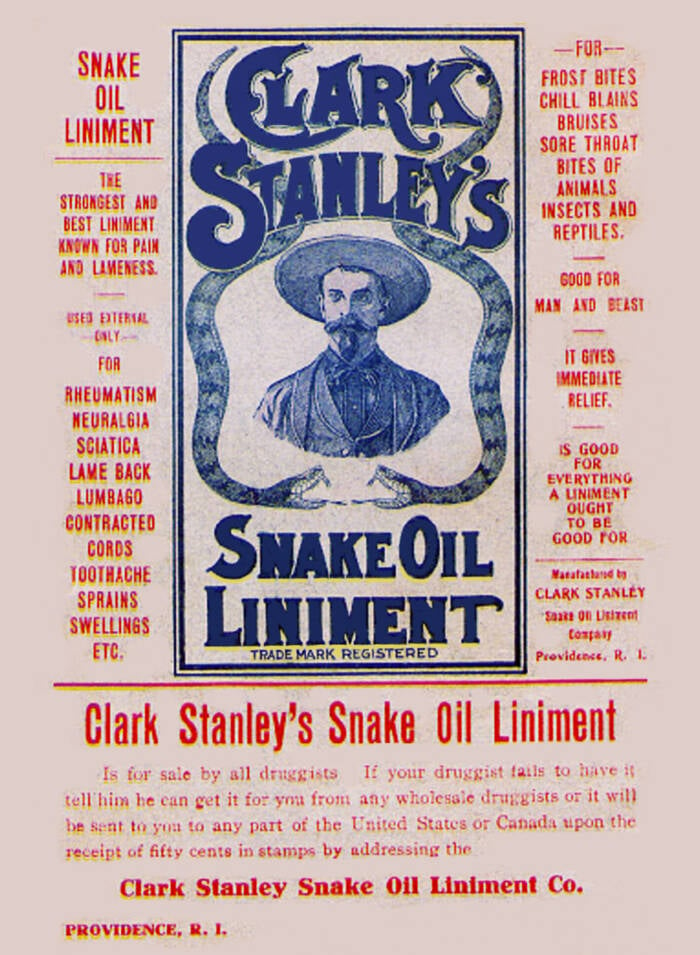

At the turn of the 20th century, a scam artist named Clark Stanley advertised bottles of rattlesnake oil that purportedly treated everything from arthritis to sore throats — but the product was really just mineral oil and beef fat.

Public DomainClark Stanley declared himself the “Rattlesnake King” and claimed that his liniment could cure man and beast.

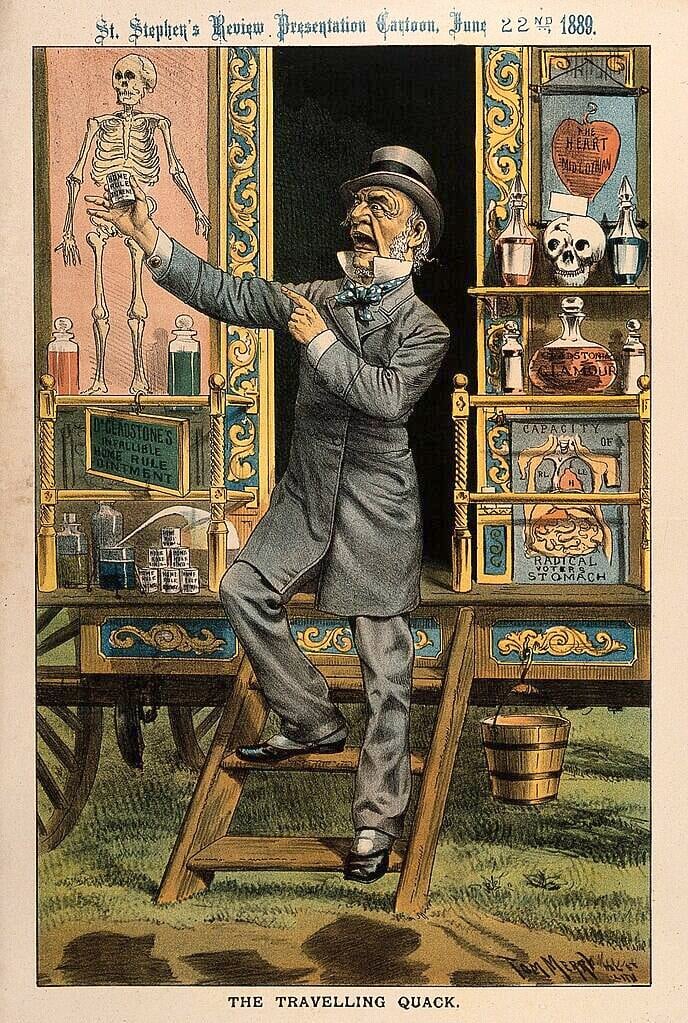

The 19th century was the golden age for con men. Quacks could ride into town and promise that a swig of their medicine could cure any ailment. These charlatans became known as snake oil salesmen. But where does the term “snake oil” come from?

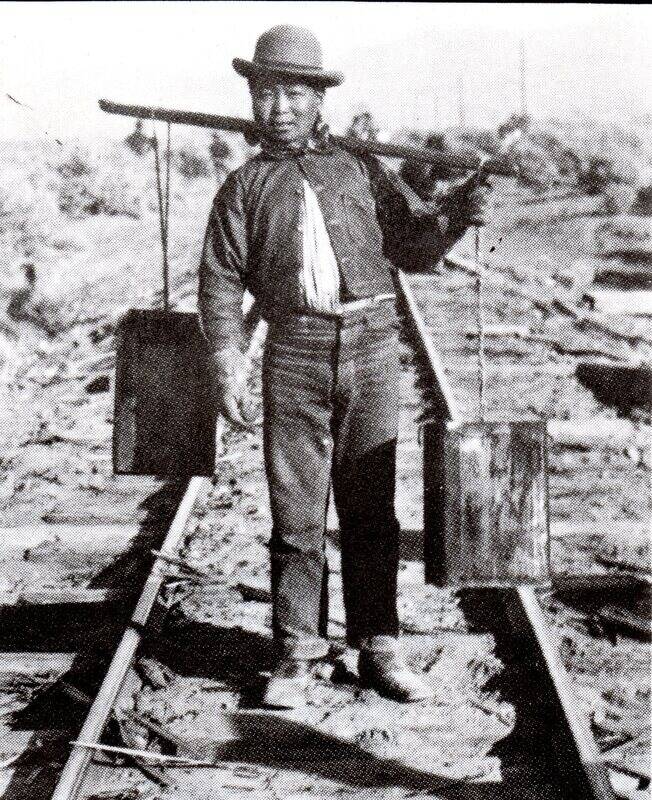

In the mid-19th century, railroad workers who had immigrated to the United States from China used the oil from Chinese water snakes to ease their joints after long days of hard labor. This original treatment actually worked — but then the scammers jumped on board.

In 1893, a man named Clark Stanley introduced his “rattlesnake oil” at the Chicago World’s Fair — but it didn’t have a drop of snake in it. At the time, there was little to no regulation in the American pharmaceutical industry, so hucksters like Stanley could make whatever claims they wanted about their products.

As new federal laws were passed in the early 20th century, these seedy salesmen were put out of business. However, “snake oil” is still used to this day to describe a worthless remedy promoted as a solution to a problem.

The Legitimate Origin Of Snake Oil

In the mid-19th century, around 180,000 Chinese laborers came to the United States. Many of them took jobs building the Transcontinental Railroad. These backbreaking, low-wage positions often left the workers in physical pain.

Chinese railroad workers brought medicines from their home country to help them cope. One of these was snake oil. According to a 2007 report in Scientific American, the oil, which was derived from the Chinese water snake, contained high levels of inflammation-reducing omega-3 fatty acids. When workers rubbed the product on their stiff joints, they felt better.

Northeastern Nevada Historical Society and MuseumTens of thousands of Chinese railroad workers connected the West coast to the rest of the country by rail.

It didn’t take long for American scammers to sense a money-making opportunity. Clark Stanley, the original snake oil salesman, made a fortune duping people into buying rattlesnake oil.

However, Stanley erased the Chinese railroad workers who introduced America to their cure. Instead, he made up a story of Hopi medicine men who taught him their secrets. His product was a hit — but it didn’t actually come from snakes at all.

The Rise Of Patent Medicine In The 19th Century

A legitimate Chinese treatment quickly turned into an American fraud thanks to the rise of patent medicine. These “cures” promised relief from aches and pains, along with more serious conditions like cancer. However, there was no regulation over the substances they included or their claims of effectiveness.

As a result, patent medicines rarely contained the ingredients listed on the label — if the label listed ingredients at all. Many included high levels of alcohol, morphine, or cocaine, which masked symptoms and gave users the false impression that the treatments worked.

Michael Coghlan/Wikimedia CommonsPatent medicines faced zero regulations on their ingredients or their sky-high promises.

Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Syrup, marketed to the mothers of fussy babies, did not require a prescription. Women could simply visit the local drugstore and pick up a bottle. But the “soothing syrup” actually contained morphine and alcohol, which proved deadly for some infants who were given the unregulated medicine.

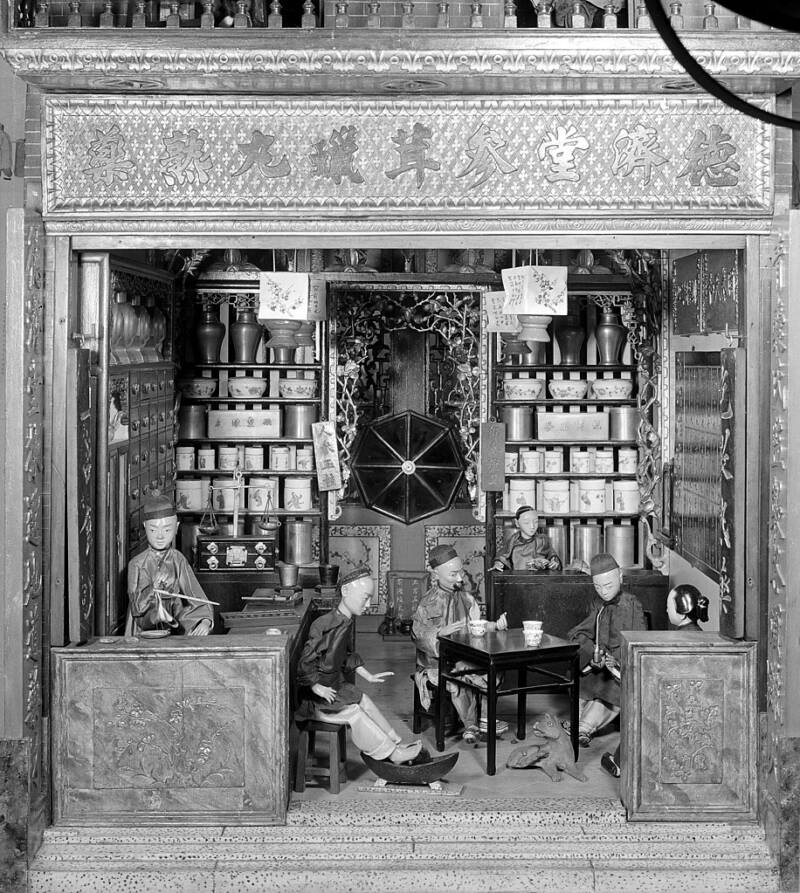

Chinese water snake oil truly did work, as recent tests have demonstrated. According to Scientific American, 20 percent of the oil from the Asian reptiles is made up of the omega-3 acid eicosapentaenoic (EPA), which can lower inflammation. However, importing medicine across the Pacific proved impractical, so Americans decided to create their own version.

The rattlesnakes of the American West might not boast the omega-3s of Chinese water snakes — their oil contains just a little over eight percent EPA — but they were plentiful. Consumers who’d heard rumors about the effective Chinese snake oil could be convinced to buy rattlesnake oil. That’s where Clark Stanley came in.

Clark Stanley, The Rattlesnake King

In 1893, entrepreneur Clark Stanley brought rattlesnakes to the Chicago World’s Fair. As onlookers watched, Stanley pulled a live snake from a sack, sliced it apart, and tossed the pieces into boiling water. Next, he skimmed fat from the cauldron to create “Clark Stanley’s Snake Oil Liniment.”

After witnessing the spectacle, the crowd surged to buy the Rattlesnake King’s patent medicine.

And what about the Chinese medicine that started the trend? Stanley erased history, claiming in his self-published autobiography that he learned how to make snake oil while visiting a Hopi or “Moki” tribe in Arizona. He wrote, “As I was thought a great deal of by the medicine man he gave me the secret of making the Snake Oil Medicine, which is now named Clark Stanley’s Snake Oil Liniment. Snake Oil is not a new discovery, it has been in use by the Moki’s and other Indian tribes for many generations, and I have made an improvement on the original formula.”

Wellcome ImagesAn 1880s cartoon condemns the quack doctors who sold dubious cures.

Stanley’s ads ran in newspapers across the country, vowing “immediate relief” from “pain and lameness.” Suffering from sciatica? Stanley’s oil treated that. How about animal bites? The ads promised relief. Have a lame horse? The liniment was “good for man and beast.”

“If your druggist fails to have it,” the ad told potential customers, “tell him he can get it for you from any wholesale druggists.” Or, buyers could simply send 50 cents in stamps to Stanley to receive a bottle through the mail.

Demand was so high that Stanley opened facilities in Rhode Island and Massachusetts to pump out the liniment. He claimed that he owned a snake farm in Texas to supply the main ingredient. However, soon after his first demonstration, Stanley realized that it wasn’t practical to mass-produce rattlesnake oil, so he quickly cut snake from his product altogether — without changing the label.

What was in Clark Stanley’s Snake Oil? Mineral oil, beef fat, red pepper, and turpentine.

He continued to sell this worthless remedy for decades, but as federal law began to target patent medicines in the early 20th century, Stanley’s liniment faced closer scrutiny.

Catching A Snake Oil Salesman

Clark Stanley’s Snake Oil wasn’t deadly like some other patent medicines. But it also didn’t work. In 1906, the Pure Food and Drug Act stated that manufacturers like Stanley couldn’t market their medicines with lies. And all patent medicines had to list harmful ingredients like cocaine and morphine.

Still, Stanley kept selling his liniment. Then, in 1917, the federal government intercepted a shipment of his product. Investigators tested the oil and found no trace of snakes.

The government fined Stanley for misleading consumers. However, the Rattlesnake King paid a fine of just $20 (the equivalent of around $550 in today’s currency), shut down his production facilities, and faded quietly out of the spotlight. His run-in with the law only proved that snake oil salesmen could get away with it.

Wellcome ImagesChinese pharmacies sold oil made from Chinese water snakes. This 1881 model of a Canton pharmacy captures the setting.

Many of the patent medicines of the 19th and early 20th centuries continued to crumble under scrutiny. With new consumer protection laws, more and more men like Clark Stanley had to close up shop. Shining a light on the deceptive practices of quacks gave birth to the phrase “snake oil salesman.”

By the early 20th century, Americans knew that fraudsters like Stanley had inflated their promises. The Rattlesnake King was among the “crooked creatures of a thousand dubious trades” condemned in the 1927 poem “John Brown’s Body” by Stephen Vincent Benét that criticized “sellers of snake-oil balm and lucky rings.”

Snake oil itself became synonymous with fake cures. While the original Chinese treatment worked, American con men destroyed the medicine’s reputation to turn a buck.

After learning about how Clark Stanley scammed thousands with his “snake oil,” read about history’s most infamous con artists. Then, learn more about the secret history of Coca-Cola.