Bringing in the world's best and brightest innovators, the 1893 Chicago World's Fair transformed the way we look at exhibitions forever.

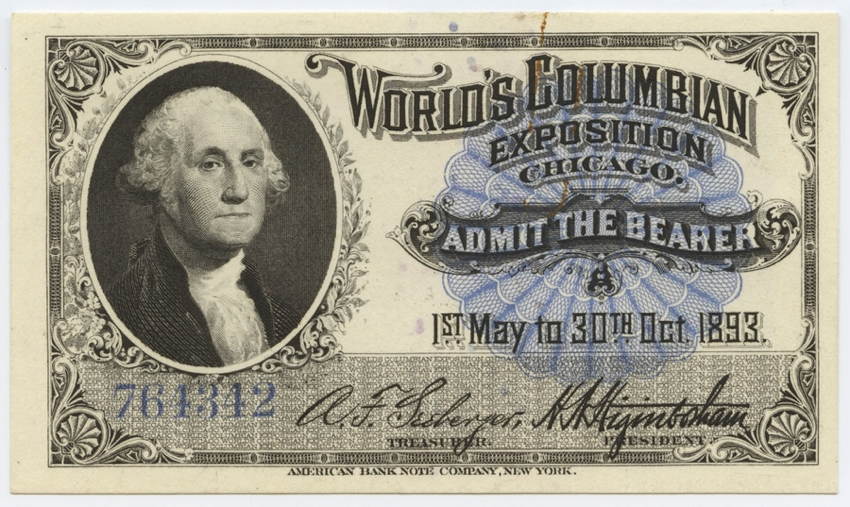

A ticket to the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair.

Up to the moment that the Chicago World’s Fair opened to the public on May 1, 1893, crews scrambled to replant landscaping that had been washed away in a torrential rain storm.

Puddles drowned the newly sodded lawns and some paint was still wet, but to the eyes of that day’s fairgoers, it was nothing short of a photo finish. The few remaining pieces of the Fair dazzle today’s viewers just like they did over a century ago.

Rather than a simple map, enjoy UCLA’s three-dimensional recreation of the Fair:

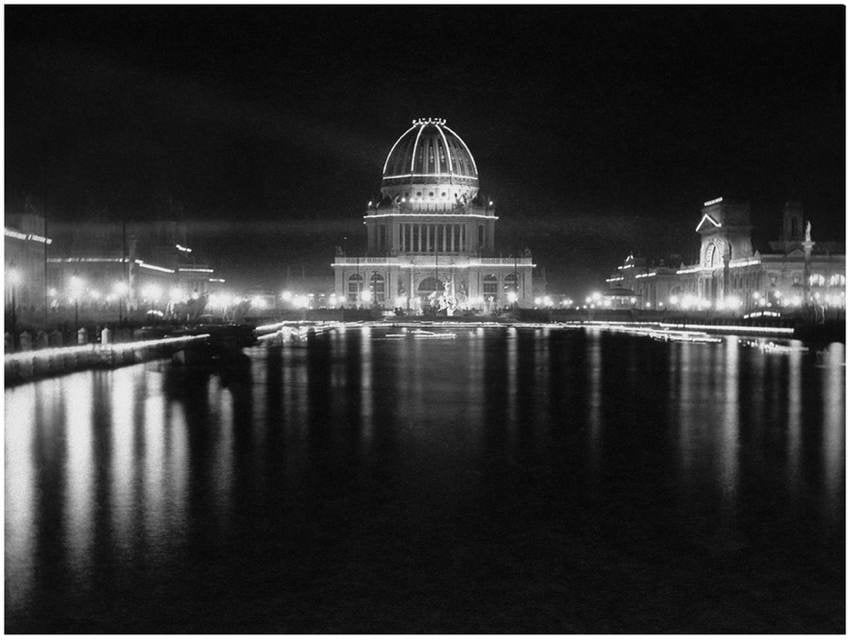

In the nineteenth century, cities were filthy places. Factory pollution and dust clogged the air. So when fairgoers were greeted by the glimmering Court of Honor, nicknamed the White City, it seemed like they had been transported to another world. Overseeing the Fair’s design and construction, Daniel Burnham had the huge neoclassical buildings coated in soft white paint so that they would “glow” in the sunlight.

The real spectacle began after sunset. After all, it was at the White City where Nikola Tesla’s game-changing alternating current—which was chosen over Thomas Edison’s direct current to power the exposition—literally gave light to the fair at a time when lighted streets were still quite novel.

Source: Element 14

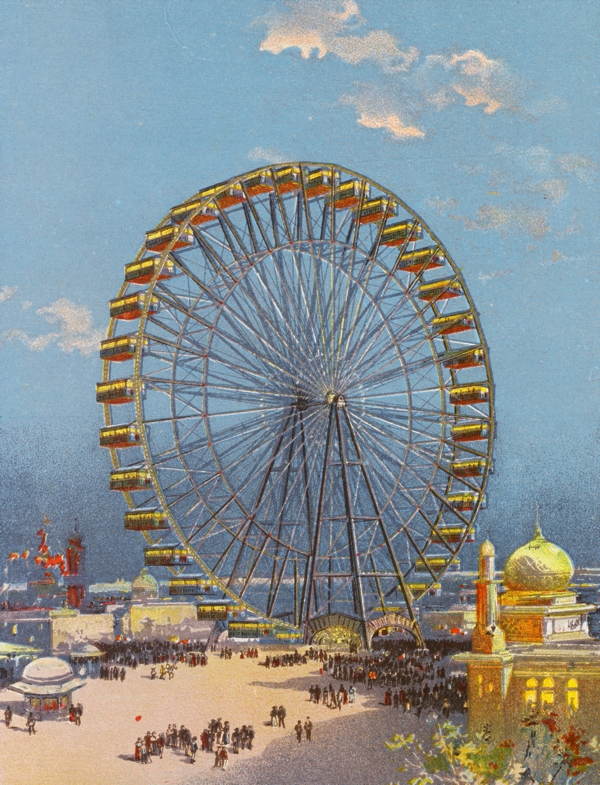

The Columbian Exposition, or the Chicago World’s Fair, is often called the Fair that Changed America: it spanned 600 acres and introduced fairgoers to wonders of electricity such as elevators and the first electric chair; products we now take for granted like the zipper, Cream of Wheat, and Cracker Jacks; and presented viewers with a look at Edison’s kinetoscope and a listen to the first voice recording. The Midway Plaisance, from which we get the term “midway,” included George G.W. Ferris’s new Wheel.

Source: Explore History

The Midway was also home to some less seemly exhibits. For example, people of faraway nations were put on display like animals: Lapps, Eskimos, Zulu, and opium smokers from China.

Still, the Fair;s lasting vestiges are beautiful specimens. And if the Court of Honor was a ring, the Statue of the Republic was its jewel.

Daniel Chester French, who also sculpted Abraham Lincoln for the Lincoln Memorial, sculpted the much-vaunted statue. The work received its nickname, Big Mary, since it stood a full six-stories tall.

/caption]

A more-permanent version of the statue was crafted after the Fair ended, but at one-third the size. It can be seen today off of Lakeshore, where E. Hayes Drive meets S. Richards Drive.

The Palace of Fine Arts is one of the Fair’s most impressive remaining buildings, thanks to some forward thinking on behalf of the Fair’s architects.

Chicago had a history of fires, making art collectors and museums wary of sending art to the Fair. So Charles Atwood, a Burnham architect, had the Palace fireproofed. The Palace has since been renovated and now serves as the Museum of Science and Industry but it ultimately looks the same as it did in 1893, except that it is no longer white.

[caption id="attachment_27818" align="aligncenter" width="850"] Source: Museum of Science and Industry

Source: Museum of Science and Industry

In realizing their drafted fairground dream, the Fair’s organizers also sought the help of some of the world’s leading landscape artists, including Frederick Law Olmsted.

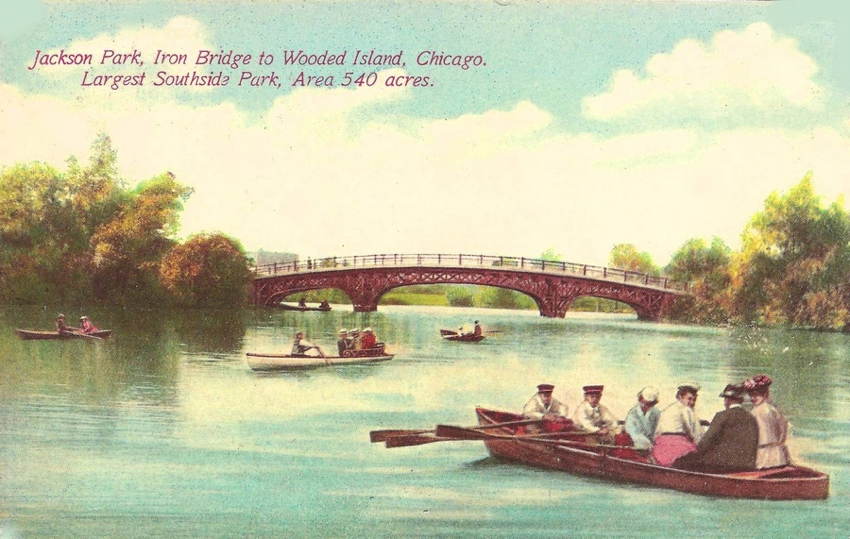

Olmsted, the man who designed New York City’s Central Park, worked as the Fair’s landscape designer. His most lasting work was the Wooded Island, seen here in a postcard circa 1910.

Source: WordPress

Today, much of the Jackson Park island serves as a bird and butterfly sanctuary. But a real show of foliage awaits visitors if they follow the path to the Osaka Japanese Garden. A few anti-Japan vandals destroyed the garden during World War II, but it has since been beautifully restored.

Source: Chicago Architecture

Another impressive Fair remnant is the Rookery, where every blueprint for the Columbian Exposition was drawn.

In 1905, the enclave’s lobby was redesigned by Frank Lloyd Wright, and today the structure is regarded as one of Chicago’s most historically significant buildings. Check out this stairwell for proof.

The World’s Columbian Exposition is worth remembering for many reasons, not all of them good. For example, America’s first serial killer, H.H. Holmes, stalked its tree-lined lanes.

However, the fact remains that in 1893, Chicago pulled off a feat of beauty and ingenuity never topped by any other world’s fair.

Check out this gorgeous photo slideshow of the Fair:

After you learn about the 1893 Chicago’s World Fair and what remains of it today, look at the HH Holmes murder house that lured in victims of the fair and haunting images from the great Chicago fire of 1871.