From the conman who invented the Ponzi scheme to the modern scam artist who built a multi-billion-dollar company on a fake medical breakthrough, these are history's most conniving grifters.

The term “con artist” or “conman” comes from one of American history’s earliest scammers, a man by the name of William Thompson. In 1849, Thompson was arrested in New York City for a slew of successful scams during which he duped unassuming passersby on the street into lending him their valuables before vanishing with them.

Thompson was consequently known among local authorities as “the confidence man,” which was eventually shortened to “con man.” But Thompson was hardly alone in his clever grifts. According to historian Karen Halttunen, approximately 10 percent of all criminals in New York City in the 1860s were con artists.

Nearly all “confidence men” or scam artists are charming. Take Victor Lustig, for example. This conman managed to “sell” the Eiffel Tower and allegedly even swindled notorious mobster Al Capone. He was fittingly dubbed “the Count” by authorities because he was so debonair.

Beyond the smooth talkers, there are also those conmen who play on people’s biases like Anna Sorokin, who cheated her way into the ranks of New York City’s elite by pretending to be a rich heiress named Anna Delvey. The scam artist’s former friends, nearly all of them wealthy socialites, alleged that she had convinced them to loan her cash for lavish vacations abroad only to never be repaid.

Indeed, conning is not a thing of the past. In today’s internet age, scams exist in the form of spam emails and catfishing campaigns.

And while cognitive scientists argue that most people today are more cautious, con artists still manage to find ways to evade the best lie detectors, leaving even the keenest people to be conned.

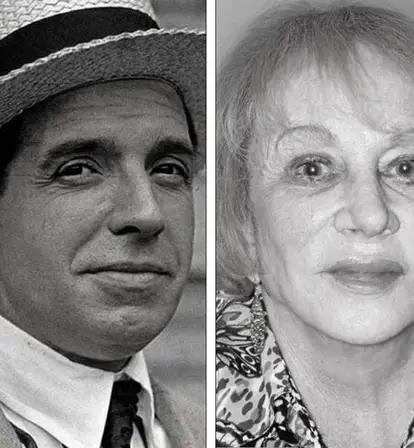

Charles Ponzi, The Most Notorious Conman In U.S. History

Leslie Jones/Boston Public LibraryThis conman and investment fraudster from the early 20th century was the namesake of the term “Ponzi scheme.”

Today, the term “Ponzi scheme” is used to describe an illegitimate operation. But the term actually came from the real-life Charles Ponzi, whose $15 million investment scheme claimed to turn the average American working man into a multimillionaire overnight.

But really, the scheme only worked to turn Ponzi himself into a multimillionaire overnight.

Charles Ponzi was an Italian immigrant who first came to the U.S. in 1903. Like most immigrants who came to America, Ponzi was looking for economic opportunity. The conman worked all kinds of odd jobs to make ends meet until he secured a job at Bank Zarossi, which served mostly Italian immigrants in Montreal, Canada.

But when the bank went bankrupt, Ponzi found himself out of a job. As a result, he began dabbling in check forgery and illegal smuggling, which landed him in prison. But after his release, Ponzi was struck with inspiration. Thanks to a letter from a business correspondent in Spain, the ambitious hustler was introduced to the international postal coupon system.

“I landed in this country with $2.50 in cash and $1 million in hopes. And those hopes never left me.”

Ponzi exploited the system by buying massive quantities of postal coupons from countries with weak economies and redeeming them in countries with stronger ones. He operated his scheme under his invented Securities Exchange Company.

The scam artist trained sales agents to pitch potential investors, telling them that they would receive double their money plus interest back within 45 days. The sales agents pulled in 10 percent commissions for every investor they managed to bring in while “subagents” pulled in five percent.

Leslie Jones/Boston Public LibraryPonzi, pictured with his gold-handled cane, heads to court in 1920 to defend himself.

Charles Ponzi’s scheme grew as investors eagerly dumped money into his business. He took the payments from sales agents and investors directly and, instead of using them to ship the stamp coupons, simply pocketed them himself. Then, he gave portions of the money to pay off previous investors, creating an infinite cycle of non-profitable investments.

His scam secured over 40,000 investors, making him a millionaire in less than six months. An article published by the Boston Post on July 24, 1920, estimated that his net worth was around $8.5 million. He had a 12-bedroom mansion, multiple cars, house staff, and a gold-handled cane.

News of Ponzi’s wealth — and the false claim that he was making others as wealthy as he was — attracted more investors. But it also invited scrutiny from federal investigators. In the end, it was Ponzi’s publicist, William McMasters, who revealed his fraudulent scheme and reported him to authorities.

The conman served three and a half years in federal prison for his scam. After he was paroled in 1925, he was sentenced to nine years in state prison on additional fraud charges. But his unmasking did little to motivate his remorse.

Charles Ponzi described his scam as “the best show ever staged on their territory since the landing of the Pilgrims!” He subsequently tried to escape from prison multiple times.

After he was released from jail in 1934, Ponzi was deported back to Italy where he died in a charity hospital in 1949 with just $75 to his name. But his name and the scheme he founded live on in infamy.