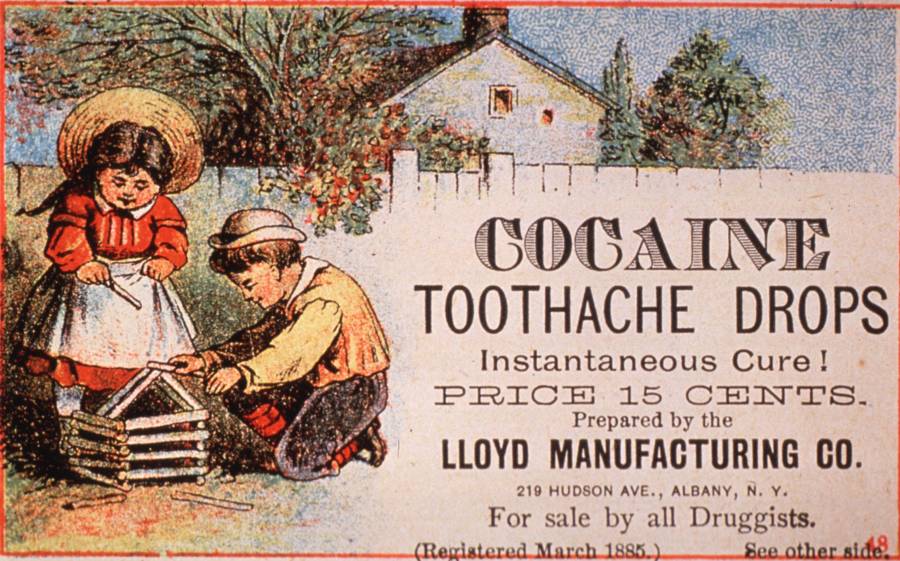

Drugs once contained all kinds of dangerous substances that were advertised as miracle cures

Wikimedia CommonsBefore drugs became regulated by the government, a number of suspect ingredients made their way into these “patent medicine.”

People have been in search of miracle medicines since the beginning of time; the more exotic the ingredients, the better chance they have of being sold. Ancient Roman women bought vials of gladiator sweat and applied it as a cosmetic, and even today “Egyptian magic” lotion (actually manufactured in Texas) is a best-seller among celebrities and plebeians alike.

The Golden Age of patent medicine was the Victorian Era, when advertisers could reach wide audiences via a variety of different formats and the marketers of these “medicines” were unchecked by federal regulations. Besides posting ads in newspapers (which had been an effective medium for selling these products since the 17th century), salesmen discovered they could bombard prospective clients by painting rocks and walls in the early 1800s. Soon people were painting wagons and roaming the streets wearing sandwich boards, resulting in such a constant swirl of salesmanship that by the 1860s Americans were already grumbling there was “no relief” from advertising “in all the earth.”

The Rise Of Patent Medicine

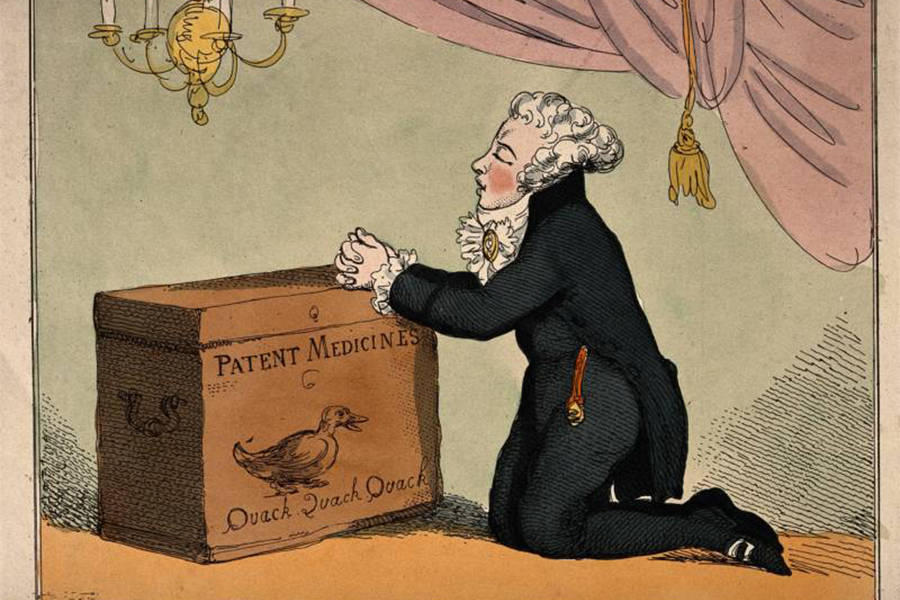

Wikimedia CommonsThis 1801 sketch mocking a patent medicine salesman shows that not everyone was susceptible to their colorful advertising

Henry T. Hembold was one of the first patent-medicine peddlers who realized the tremendous potential of using newspapers to sell his product. The buchu plant Hembold chose as his cure of choice had long been used by the natives of South Africa as both a medicine and cosmetic, and was already listed in American medical journals as useful for treating urinary and prostate problems.

Hembold decided to take a different approach to ensure his elixir stood out from the dozens of other patent medications on the market; rather than emphasize buchu’s medical uses, he cunningly focused on frightening potential customers with descriptions of horrible diseases that could be cured by the plant extract. He at first anonymously dropped pamphlets in public places titled “The Patients’ Guide, A Treatise on Diseases of Sexual Organs” that described symptoms such as “restlessness” and “the inability to contemplate disease without a feeling of horror” which, if left untreated (by buchu of course) could lead to epilepsy, insanity, or consumption.

Naturally, Hembold’s pamphlets were designed to ensure each reader recognized the symptoms of the diseases in him- or herself; horrified hypochondriacs could not buy his buchu extract fast enough. The clever peddler expanded his horizons and audiences by moving from dropping pamphlets to purchasing advertisements in the country’s most popular newspapers and magazines.

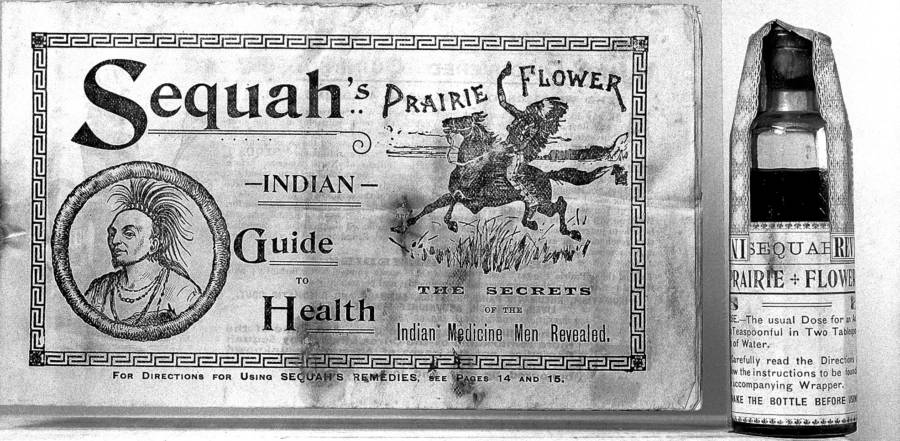

Many patent medicines boasted exotic-sounding ingredients that promised miracle cures for various ailments

Hembold made a fortune off his extract and the print industry realized that these advertisements could be a major source of income. As the journalism business boomed after the Civil War, another industry grew solely around the placement of these advertisements. Instead of copy thought up by the proprietors of these specious medicines, agencies began hiring their own writers to produce the language tailored specifically for the ads. By the late 1800s, advertising patent medicines was the main source of income for most agencies and writers, one of whom neatly summed up the entire industry stating “medicines were worthless merchandise until a demand was created.”

Other Peddlers Get On Board

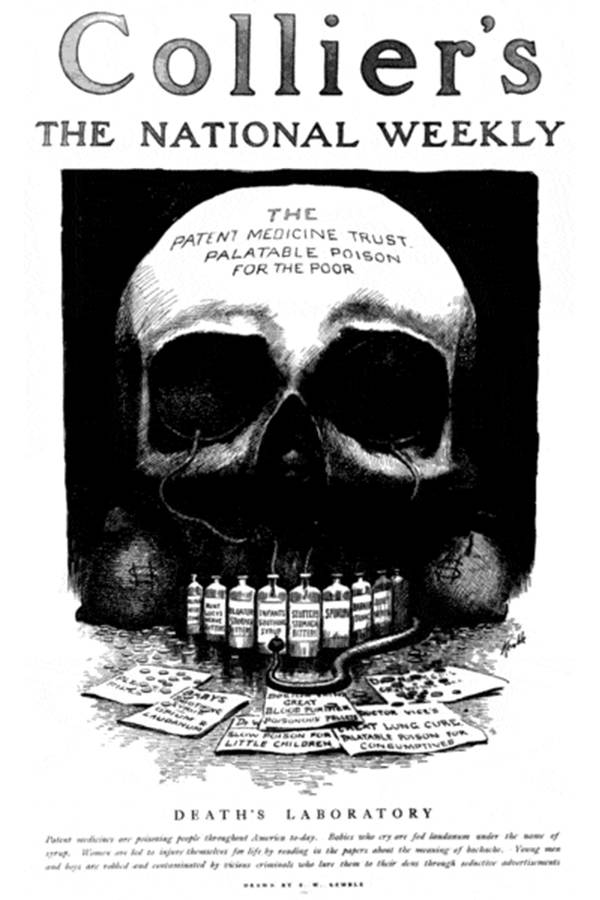

The age of patent medicine and medicine shows designed to promote them came to an end when the federal government began to more closely regulate the drug industry after muckrakers had exposed the fraudulent nature of the so-called “medicines.” The “Pure Food and Drug Act” of 1906 brought the union of advertising and patent medicine to an effective end when it required the medicines to be labeled correctly.

Wikimedia CommonsMuckrakers eventually exposed the patent medicine industry and the federal government cracked down on fraudulent advertisements

While the modern reader may be inclined to laugh at the gullibility of the Victorians, recent headlines belie the idea that today’s population is immune to suspect advertisements. The internet has allowed shady advertisers to reach numbers of people the likes of which Hembold and his colleagues could only have dreamed, and when users willingly post personal information on social media sites such as Facebook, they become easy prey.

Instead of distributing pamphlets in hopes a few of the people who saw them would be enticed into buying a sketchy elixir, today’s miracle medicine peddlers make use of powerful algorithms already in use. Since Facebook can track which users click on advertisements for things like diet pills, the algorithms they use can mathematically predict which other products the user might be willing to buy, or which other users will be susceptible to the same ads and since human nature is unlikely to change, the patent medicine peddlers will always be able to make a buck.

Next, check out the dangerous drugs that were once in these patent medicines. Then, read about the dangerous drugs you can get from your doctor right now.