When a February thunderstorm in South Africa killed two giraffes, conservation scientists began to studying how lightning strikes the animals — with intriguing results.

Wikimedia CommonsRockwood Conservation’s herd of eight giraffes was reduced to six after a heavy thunderstorm in February.

On the last day of February, a South African rainstorm in the Northern Cape saw two giraffes struck by lightning. The freak 2020 incident at Rockwood Conservation naturally came as a shock, though a new study suggests it shouldn’t have — as giraffes are inherently prone to being struck.

For conservation scientists like Ciska Scheijen, who works at the animal-friendly expanse, the incident represented a valuable learning opportunity. According to IFL Science, it’s long been argued that the mere height of giraffes could attract lightning — but this event finally yielded actual data.

While Scheijen clarified her observations were borne out of mere chance, she published her findings in the African Journal of Ecology in hopes they inspire further research. As it stands, it appears that giraffe height isn’t the only factor — but the knob-like horns atop their heads might act as lightning rods.

The thunderstorm in question was heavy but brief, with tremendous rainfall and lightning. While conservationists saw the park’s entire herd of eight giraffes together one day earlier, the storm clouded the researchers’ visibility.

African Journal of EcologyThe left skull has a clear rupture between its two ossicones, suggesting a direct hit.

“It came as a bit of a s surprise to me because the whole day was quite quiet in weather, and suddenly there was this big storm,” Ciska Scheijen told NewScientist.

When the weather lifted and things cleared, it became clear almost immediately that something was wrong. Scheijen recalled seeing only six of the eight giraffes, which was unusual for this herd. Venturing into the expanse, she found a five-year-old female and a younger giraffe, both dead.

Lying prone a few feet apart, Scheijen noted that they were found in the same vicinity they were last observed in. Further suggesting it was the storm that killed them was an enormous fracture in the skull of the elder giraffe. The right ossicone, or horn-like knob atop its head, was ruptured wide open.

Unlike other animals that suffered a direct hit, this particular carcass showed no singe marks. Nonetheless, Scheijen and Rockwood Ranger Frans Moleko Kaweng did note a peculiar stench — the glaring smell of ammonia. The dead animal’s flesh didn’t even appeal to nearby scavengers.

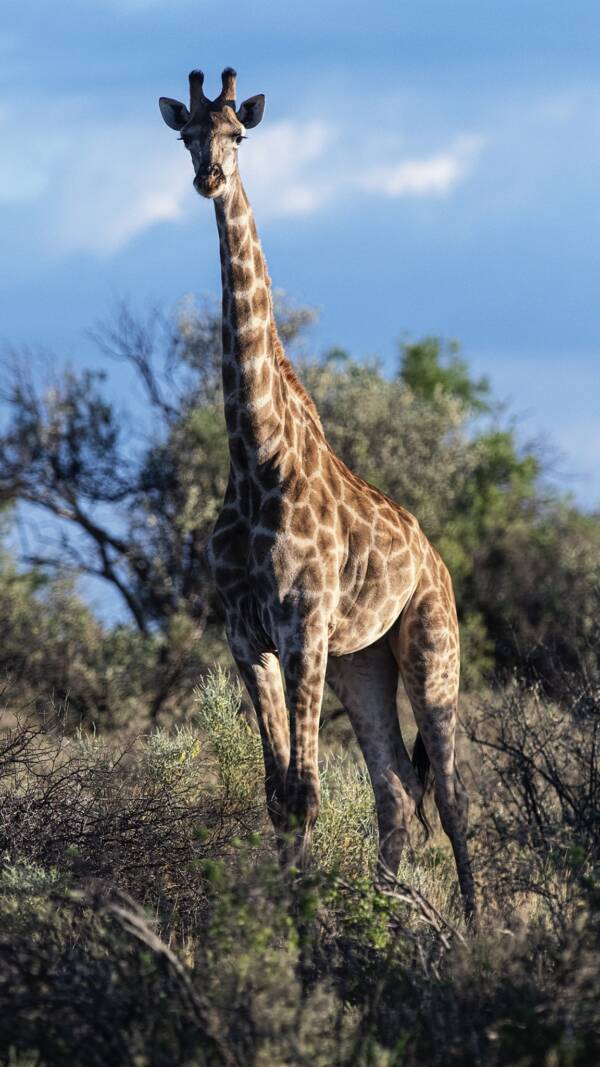

FacebookThe sheer stature of giraffes could pose a serious problem during thunderstorms, as the animals are often the tallest objects around.

People have wondered whether or not giraffes get hit by lightning more than other animals for quite some time now. The question is so ubiquitous that it spawned one of the most liked posts ever published on Reddit, for instance.

As for this latest incident, it matches a previous 2014 study entirely — and highly indicates that these animals are indeed vulnerable to lightning strikes. The older study not only showed the delayed scavenging observed in February’s incident but the overwhelming scent of ammonia, as well.

Ultimately, there are four ways that a lightning strike can kill a wild animal. It either hits them directly, kills them with a side flash that strikes a nearby object, takes their life after a discharge of lightning hits the ground they’re walking on, or kills them after they’ve touched a stricken object.

Scheijen believes that the elder giraffes at Rockwood died of a direct hit, while the younger one died as a result of being near it or in direct contact with it. The giraffes were last seen somewhat removed from any trees, and the elder’s sizable rupture further supports this hypothesis.

“I would not say the ossicones per se act as a lightning rod, but the towering height of the giraffes could,” said Scheijen. “If they are the highest point in the vicinity, then chances may be high that they are the ones at greatest risk in the area to get struck by lightning.”

During particularly powerful thunderstorms, with no trees taller than them to attract the strikes, the rationale is entirely sensical. On the other hand, it’s unclear whether giraffes have adapted to this.

Observations by Scheijen herself, while not yet published, have found that giraffes walk around 13 percent shorter distances during rainfall. As such, their behavior might have evolved specifically to avoid this type of fatality — but further research will be needed to assess when and how any adaptations may have occurred.

After learning about the horn-like knobs on a giraffe’s head acting like dangerous lightning rods, read about giraffes being on their way to “silent extinction” due to American trophy hunting. Then, learn what happens when lightning strikes the human body.