"By identifying the vast majority of high-risk viruses that have not yet emerged, we’ll be able to design new strategies to reduce the risk of future pandemics."

pixaby

Wouldn’t it be great if we were able to stop the outbreak of a major virus like Zika, SARS, or Swine Flu before it even started?

The Global Virome Project (GVP), launching in 2018, is aiming to do just that.

Today, standard response when it comes to the outbreak of one of these viruses is almost always reactionary: The outbreak occurs, people panic, the public health sector scrambles to find out where it’s coming from and how to stop it.

In the meantime, more and more people get infected and a lot of money is spent.

But focusing on fixing each outbreak after it happens leaves us vulnerable to the next ebola-esque pandemic.

All That’s Interesting spoke with Dr. Peter Daszak, a parasitologist involved in spearheading the GVP. He is also the president of the EcoHealth Alliance.

“By identifying the vast majority of high-risk viruses that have not yet emerged, we’ll be able to design new strategies to reduce the risk of future pandemics,” said Daszak.

“A good analogy is global terrorism,” he said. “We don’t wait for a terrorist attack and then try to respond afterwards – we have spent the last few decades building a global understanding of who terrorists are, where they are based, and how to track their communications so we can disrupt their plans ahead of an attack.”

The strategy of the GVP is essentially that, but for viruses. The GVP will do this by analyzing the diversity and ecology of viral threats, as well as what drives them to emerge.

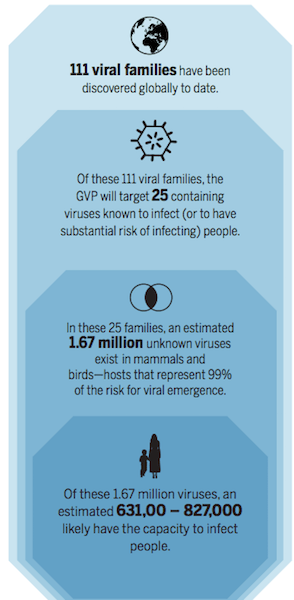

Right now, there are 25 viral families that contain 263 viruses known to infect humans.

It’s estimated that around 1.67 million undiscovered viral species exist in mammal and bird hosts. Of these, it’s estimated that between 631,000 to 827,000 are zoonoses. Zoonoses are viruses that have the potential to be transmitted from the animals to humans.

That means there are somewhere between 631,000 to 827,000 viruses we don’t know about that have the potential to become the next big pandemic outbreak.

That’s a lot of potential diseases.

Additionally, the rate of zoonotic viral spillover, which is the transferring of disease from animals to humans, is rising with exponential growth due to our global footprint and our ability to travel all over.

The pandemic crisis we have experienced in the past happened due to lack of information on potentially dangerous animals. “These are usually new viruses that originate in wildlife species that carry their viruses harmlessly until we give them the opportunity to infect us,” explained Daszak.

The GVP’s emphasis on large-scale sampling will be carried out by doing fieldwork in all the areas where these viral-host relationships are known to exist. The fieldwork and subsequent lab testing are expected to give insight into their histories and patterns of viral emergence, with the end result being viral discovery.

Science MagazineInfographic showing the number of unknown viruses the GVP plans on identifying.

One potential obstacle of the GVP is cost. Analysis done by the GVP team estimated that the research for the new viruses and the characterization of their risk for infected people with the current technology available would be over $7 billion.

However, past analysis shows that when it comes to sampling projects, a really large majority of the discoveries are found in the earliest stage of the project. Identifying the last few, rare viruses would be where most of that cost comes from.

Research indicates that a majority of the unknown viruses could be discovered, characterized, and assessed for about $1.2 billion dollars and complete within 10 years.

That means that only 16% of the money needed would cover 70% of the research.

The costly viruses that remain undiscovered would be the rarest ones. So they would be much less of a public health risk.

Since 2016, stakeholders from Asia, Africa, the Americas, and Europe have been meeting to design a framework for all aspect of the GVP.

Once such aspect is transparency. “The goal of the GVP is to get the information out as rapidly as possible to the public, to agencies, countries, and to scientists,” Daszak told ATI. “That means when a new virus is sequenced, the genetic code will be checked, verified and made public, probably within a few days or weeks of the lab results coming through.”

So how will this benefit the general public?

“Knowing the sequence of the majority of viruses that have potential to infect people means that when an outbreak begins, we can screen people for these new viruses,” Daszak told us. Additionally, “we can screen people for these new viruses and more rapidly identify the cause, and the pathway of emergence.”

Another benefit is the reduced risk of catching a virus from an animal that was previously unrecognized as a threat.

As Daszak put it, “if the GVP shows that certain wildlife populations have a high number of potential risk viruses, and these wildlife species are traded for food, then steps could be taken to ban their hunting or remove them from wildlife markets as a preventative measure.”

Not only would this be a health benefit, but it would also benefit the conservation of wildlife.

With the initiative of the Global Virome Project, we could be entering a new era. One that will focus on the prevention of global pandemics, rather than the rush to cure them.

Now read about, 6 diseases global warming can initiate or intensify. Then, read about these HIV patients who no longer have the virus after taking a new treatment.