Today, New Zealand is all that remains of the lost continent of Zealandia — but 30 million years ago, it was a verdant landscape filled with volcanoes and teeming with life.

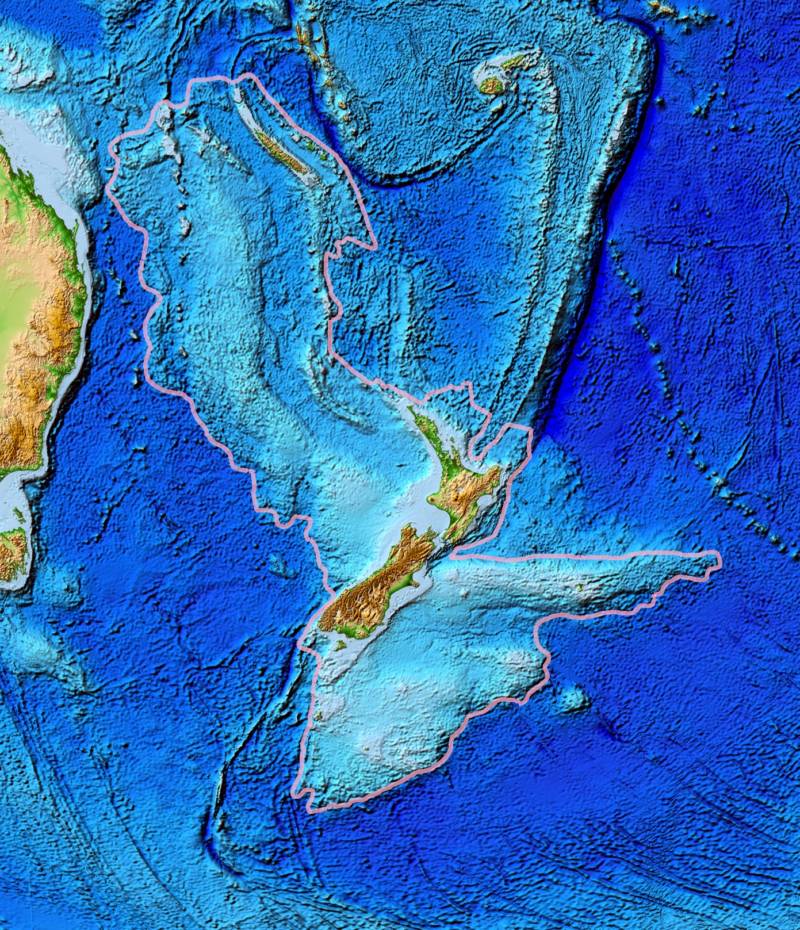

N. Mortimer et al./GSA TodayMap of Earth’s continents including Zealandia.

Everyone knows the story of Atlantis, and while that’s probably just a myth, sunken landmasses are very real — and few are more fascinating than Zealandia, the continent lurking beneath New Zealand.

Mostly submerged and stretching almost two million square miles, Zealandia has long piqued the interest of scientists. The official study of the area began in the 1990s when oceanographer Bruce Luyendyk noticed anomalies on the seafloor while studying the prehistoric supercontinent of Gondwana.

Since then, scientists have determined that Zealandia separated from what’s now Australia and Antarctica around 80 million years ago and sank beneath the South Pacific 60 million years later. In just the last few years, an extensive survey of sunken land has mapped its geography in detail. This research also confirmed that Zealandia is Earth’s eighth continent.

As one scientist put it, “We’re only just starting to discover Zealandia’s secrets.”

The Discovery Of Zealandia And Early Research Into The Lost Continent

Zealandia is a submerged continent that mostly lies deep beneath the waves of the Pacific — but it’s inhabited.

That’s because roughly six percent of the landmass is still above sea level as New Zealand and its outlying islands. These are the highest points of what was once a much larger expanse of land.

Wikimedia CommonsA topographical map of Zealandia, with New Zealand showing as the major landform. The east coast of Australia is on the left.

As a result, Zealandia wasn’t so much discovered as it was recognized.

In 1995, an American geophysicist and oceanographer named Bruce Luyendyk noticed Zealandia for the first time. Luyendyk was studying Gondwana — a piece of the supercontinent Pangea that geologists think split off roughly 180 million years ago to give us present-day South America, Africa, India, Australia, and Antarctica — when he made the find.

Luyendyk had been studying the region since the 1980s. He was trying to match Antarctica’s geological features with the edges of New Zealand, a project akin to trying to fit pieces of a crumbling puzzle back together.

This work led Luyendyk and his fellow researchers to take a closer look at the seabed around New Zealand. What they found astonished them: The rock beneath the island nation might constitute a continent in its own right.

What Makes A Continent?

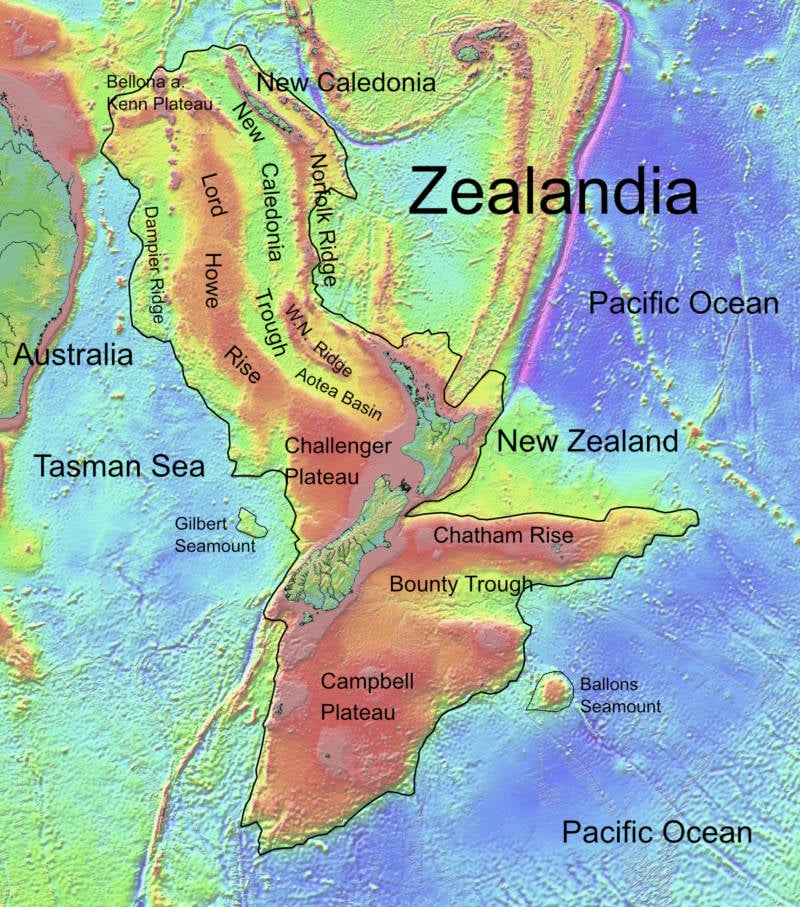

Wikimedia CommonsA map of Zealandia, outlining important points. New Caledonia is to the north. The Tasman Sea is to the west.

Most people learn in school that there are seven continents: North America, South America, Europe, Africa, Asia, Antarctica, and Australia. However, in a 2017 study published by the Geological Society of America, geologists posited that there are only six, as Europe and Asia can be considered a single continent.

Whether Zealandia is considered the seventh or the eighth continent, then, was up for debate. Still, regardless of its number, geologists argued that it should be considered a continent in its own right.

In the study, the scientists explained that the rock beneath New Zealand, according to Luyendyk’s calculations, meets the criteria that classify a landmass as a continent. Luyendyk called the area Zealandia when he recognized that New Zealand and its outlying islands weren’t actually disparate. It wasn’t long before other researchers took up the cause and pointed to all the qualities that made Zealandia fundamentally the same as other continents — just underwater.

Wikimedia CommonsBall’s Pyramid, a dramatic reminder of Zealandia’s volcanic-formed landscape.

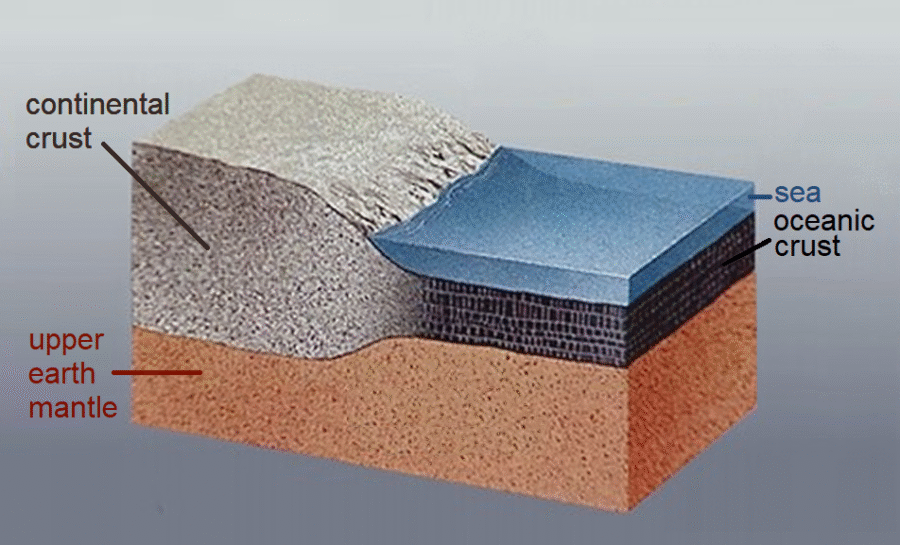

Zealandia is raised above the ocean floor, which means there’s a clear difference between the submerged landmass and the surrounding seabed, and not just in their respective heights. Zealandia, unlike the seafloor around it, is made from the bulkier, less dense material that forms continental crusts.

The composition of this material indeed meets the requirements for a continent. Zealandia is made up of three separate types of rock: igneous, metamorphic, and sedimentary. This variety reveals that it was formed and shaped by volcanic activity, heat, pressure, and erosion, just like the other continents.

Zealandia is also too big to be considered just a continental fragment. Although some scientists argued that Zealandia better deserved the less impressive designation of a microcontinent, others pushed back, noting that the rock beneath New Zealand is six times larger than even the biggest recognized microcontinent, Madagascar.

Wikimedia CommonsA simplified look at the layers of Zealandia’s continental and oceanic crust.

Whether Zealandia constitutes a continent or not can seem like a rather dry and technical point for scientists to argue over. However, the answer has real consequences for the region economically.

The United Nations determines a country’s right to drill offshore based on continental boundaries — and if the entire landmass of Zealandia belongs to New Zealand, that significantly changes the island nation’s fortunes.

By some estimates, as reported by Business Insider in 2017, tens of billions of dollars worth of fossil fuels suddenly became available to the country once Zealandia was recognized as Earth’s eighth continent.

But while most of Zealandia lies beneath the ocean today, it was once a vibrant landmass teeming with life.

Piecing Together Zealandia’s History

Few teams did more to underline Zealandia’s right to continent status than the expedition that set out to drill into Zealandia’s submerged rock in 2017.

The project was a tricky one. The lost eighth continent is hidden beneath two-thirds of a mile of water. To get a range of samples, the researchers had to drill 4,000 feet into the sediment over a period of nine weeks.

Their efforts proved fruitful. Geologists believe that Zealandia separated from Antarctica somewhere between 85 and 130 million years ago and then broke off from Australia between 60 and 85 million years ago. This 2017 research confirmed that theory and further posited that, as Zealandia separated from Australia, its crust stretched and thinned until it dropped to the bottom of the ocean.

Wikimedia CommonsMountains in southern New Zealand that are remnants of how Zealandia was formed.

No human ever saw the continent above the water, but researchers were able to find countless fossils, crushed shells, and pollen samples that suggest that the continent spent more time than scientists previously thought as a landmass above the surface. This means that, for a time, animals easily crossed between the continent’s highest points, and plants covered its tropical peaks.

Wikimedia CommonsFossils of tiny shells found in Zealandia alongside a euro coin for comparison.

This discovery was a critical piece in several ongoing puzzles. First, the discovery that the region’s climate was once tropical offers scientists new climate data that doesn’t just help them understand the past but also makes them better able to predict climate shifts in the future.

The research also answered longstanding questions about how the region’s animals evolved and spread from continent to continent. It paints a fascinating new picture of Zealandia as a verdant jungle full of prehistoric life — a jungle that’s now at the bottom of the ocean.

Mapping Earth’s ‘Hidden’ Eighth Continent

Since Zealandia was designated as a continent in 2017, scientists have been working to map its boundaries. This is easier said than done, considering so much of the continent is underwater.

“We’re only just starting to discover Zealandia’s secrets,” said Dr. Derya Gürer, an earth scientist at the University of Queensland. “It’s remained hidden in plain sight until recently and is notoriously difficult to study.”

Dan Buehler/University of QueenslandDr. Gürer and the Schmidt Ocean Institute’s research vessel, Falkor.

The University of Queensland has teamed up with the Schmidt Ocean Institute to map the continent. As the chief scientist on the project, Gürer spent 28 days mapping 14,285 square miles along Zealandia’s northwestern continent.

“Our expedition collected seafloor topographic and magnetic data to gain a better understanding of how the narrow connection between the Tasman and Coral Seas in the Cato Trough region — the narrow corridor between Australia and Zealandia — was formed,” Gürer explained.

However, the researchers at the University of Queensland aren’t the only ones trying to map Zealandia. In fact, one group has already come a long way in revealing the continent’s history.

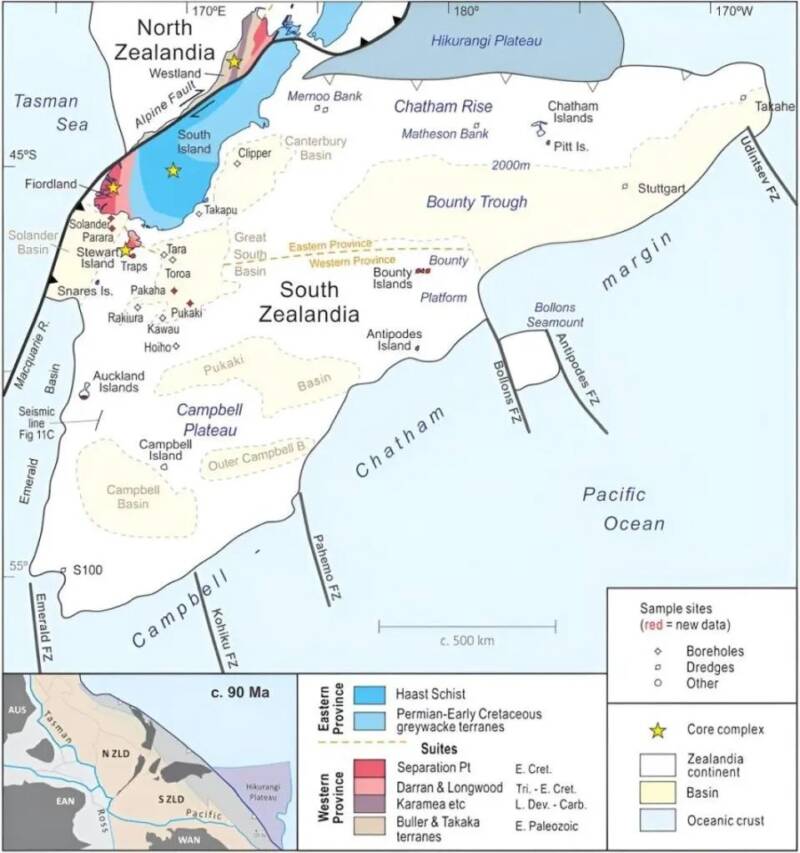

Mortimer et al. 2023/TectonicsBy mapping the northern end of Zealandia, researchers were able to infer about the geological makeup of the south.

In 2023, members of the Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences published a study in Tectonics on their methods for locating the hidden continent. Using geochronology, or the dating of rocks by measuring radioactive decay, and analysis of magnetic anomalies, researchers were able to both map out the eighth continent’s boundaries and determine the types of rocks that make up Zealandia.

Before conducting this analysis, researchers had to go out and collect samples of rocks from the continent by dredging the northern regions of Zealandia. The rock samples showed evidence of sandstone, volcanic pebbles, and basaltic lavas dating from 145 million to 40 million years old.

The scientists analyzed and interpreted magnetic anomalies within the rocks to determine patterns related to volcanic activity. This allowed them to determine where exactly the continent’s boundaries were located. Lead author Nick Mortimer and his team used this information to create a map of the major geological units across Zealandia.

“This work completes offshore reconnaissance geological mapping of the entire Zealandia continent,” the team concluded. The study also revealed how the crust of Zealandia stretched over time, causing cracks that allowed water to fill into the land and led to the eighth continent’s underwater fate.

Wikimedia CommonsThere is much scientists don’t know about the ocean floor.

For now, scientists have their work cut out for them. The sprawling eighth continent stretches across almost two million square miles. Mortimer and his team may have successfully created a geological map of the landmass, but there is still much of Zealandia to explore.

“The seafloor is full of clues for understanding the complex geologic history of both the Australian and Zealandian continental plates,” Gürer stated. Indeed, as researchers like her press ahead in examining the secrets of the deep, excitement grows around what the lost continent can reveal.

After this look at the lost continent of Zealandia, read up on the Bimini Road in the Bahamas. Or take a look at Lemuria, another lost continent south of India.