After getting lost while leading a group of gold miners through the Colorado Rockies in the 1870s, Alfred Packer resorted to cannibalism to stay alive — but the exact circumstances of his companions' deaths are unknown.

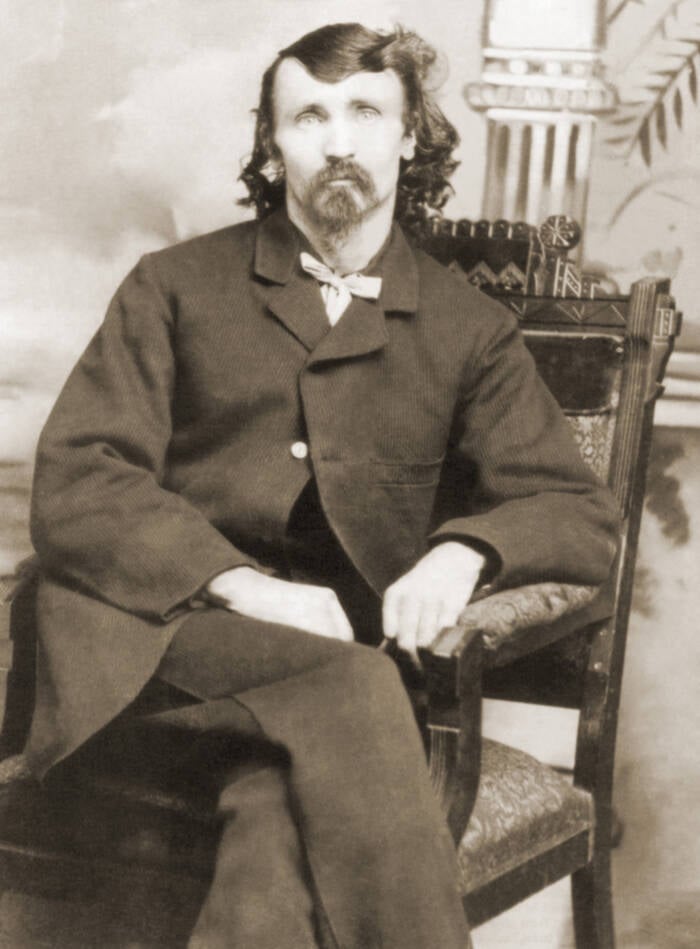

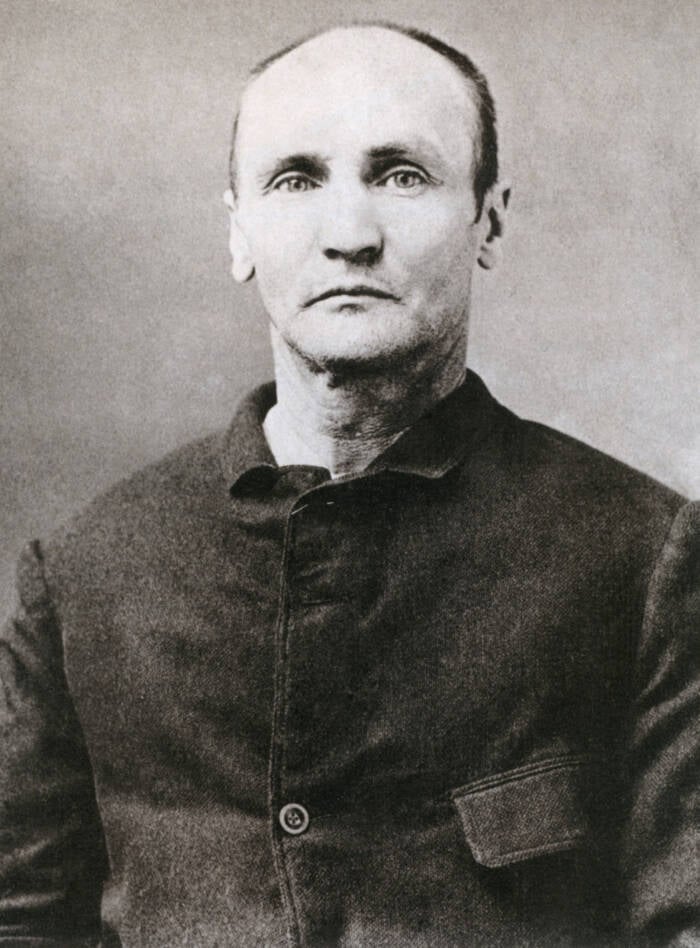

Everett Collection Historical/Alamy Stock PhotoAlfred Packer was convicted of killing and eating his five traveling companions while they were lost in the mountains.

On April 16, 1874, wilderness guide Alfred Packer arrived at the Los Pinos Indian Agency near Gunnison, Colorado, starving, freezing, and, most notably, alone. The five men Packer had been traveling with through the Rocky Mountains were nowhere to be seen. And though Packer initially claimed that he’d been separated from the others during their ardous journey, some began to suspect that he was hiding a more gruesome truth.

Such was the speculation of Charles Adams, a government official at Los Pinos, who suspected that Packer had something to do with the missing members of his party. Indeed, Packer suspiciously had money and possessions with him that had belonged to the other men. But the truth was more grisly than Adams — or anyone — had suspected.

As it turned out, Alfred Packer had cannibalized his traveling companions as they struggled to make it through the wintery mountain pass. He claimed that he had done so to survive — but not everyone believed his story.

Alfred Packer’s Life Before His Ill-Fated Journey

While intimate details about Packer’s early years are few and far between, there are some verifiable pieces of information about him. He was born near Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania on November 21, 1842 — although he would claim his birthday was actually January 21. According to Colorado Life magazine, Packer was always ambiguous about the details of his life.

In fact, even his name was up for debate. While his legal name was “Alfred Packer,” he sometimes went by “Alferd Packer.” His exact reasons for this are unknown, but the Littleton Museum reports that it may be because Packer once got a tattoo that misspelled his name.

Central Michigan University, Clark Historical Library/Library of CongressAn illustrated newspaper sketch of cannibal Alfred Packer.

That said, some things about him are known. Packer suffered from epilepsy throughout his life, which led to his discharge from two Union regiments during the Civil War. His epileptic seizures made it hard for him to hold down a job, and Packer floated from place to place, traveling west until he found himself in Colorado in 1872. There, Packer found work as a miner but lost most of his left pinky and index finger in a sledgehammer accident.

A year later, Alfred Packer was working at a different mine in Utah when he heard of a gold strike back in Colorado. Because of his experience as a wilderness guide, he was tapped to lead 21 prospectors through the mountains to the newly discovered gold fields in Breckenridge, Colorado. But though Packer was chosen for his experience, he didn’t exactly make a good impression on the other prospectors.

“He was sulky, obstinate and quarrelsome,” a would-be gold hunter named Preston Nutter, who may have disliked Packer based on the then-stigma surrounding epilepsy, recalled. “He was a petty thief willing to take things that did not belong to him, whether of any value or not.”

Despite this, the 21 men set out in November 1873. They hoped to make it rich. But only some would be lucky enough to survive the journey.

Alfred Packer Emerges From The Woods Alone

In late January 1874, Alfred Packer and his followers came across the campsite of Chief Ouray, an Ute chieftain who had a good relationship with white settlers. Their journey had not been easy, and Ouray suggested that Packer and the others wait until spring before attempting to continue.

Winter weather, Ouray warned, often hit the mountains hard. He even offered up space at his camp and suggested that the men to stay for a few months.

But though some of the men took the chieftain up on his offer, several did not. Packer and five others — George Noon, Israel Swan, James Humphrey, Frank Miller, and Shannon Wilson Bell — decided that they could not wait until spring. They set off east toward the gold fields, with Packer as guide.

Sixty-six days later, Alfred Packer emerged from the wilderness alone.

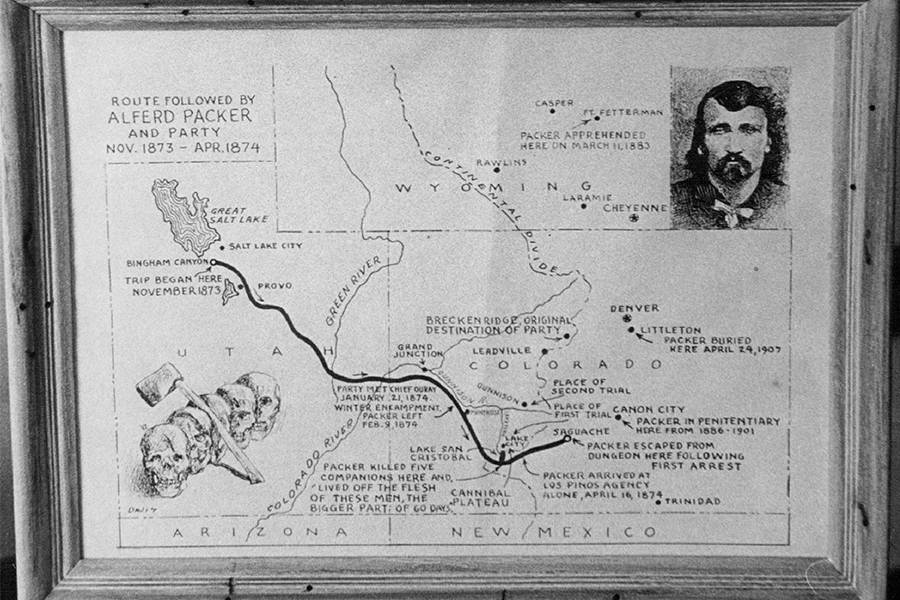

Denver Post Archives/Getty ImagesA map of the route taken by Alfred Packer and his companions.

When asked what had happened to Noon, Swan, Humphrey, Miller, and Bell, Packer claimed he did not know. Packer said that the other five men had abandoned him in the blinding snow, and that he’d been forced to survive alone on nothing more than rosebuds and rabbits. Packer claimed that he’d even eaten his moccasins in order to survive.

But it wasn’t long before some began to suspect that Packer wasn’t telling the whole story. Nutter, who’d survived his own journey through the wilderness, found it odd that Packer had Miller’s knife and Swan’s rifle. What’s more, though he’d claimed to be broke, Packer seemed flush with cash. He’d promptly bought a new horse and saddle, and spent his time — and his seemingly endless funds — drinking and playing cards at a saloon.

At that point, Charles Adams, the head of the Los Pinos Indian Agency stepped in. After convincing Packer to return to Los Pinos to help search for the missing members of his party, Adams asked Packer where he’d gotten the money. Packer’s lie about borrowing it from a local blacksmith quickly fell apart, and Adams pressed Packer to tell the truth.

“I believe these men are dead and you know something about it,” Adams said, according to Colorado Life Magazine. “You might as well tell the truth. If the matter is as I suspect, you are more to be pitied than blamed.”

Then, perhaps overburdened by guilt, Alfred Packer began to confess.

“It would not be the first time,” he told Adams, “that people had been obliged to eat each other when they were hungry.”

A Chilling Confession Of Murder And Cannibalism

According to Alfred Packer’s confession to Adams, his party was forced to turn to cannibalism after they got lost in the mountains. First, Swan died, and the others ate him. Then Humphrey perished, and was also consumed. Later, Miller was killed by Bell and Noon — Packer claimed he wasn’t present at the time — and then Bell killed Noon. Packer claimed that Bell tried to kill him as well, but that he shot him in self-defense, ate part of Bell’s body in order to survive, and then kept hiking toward Los Pinos.

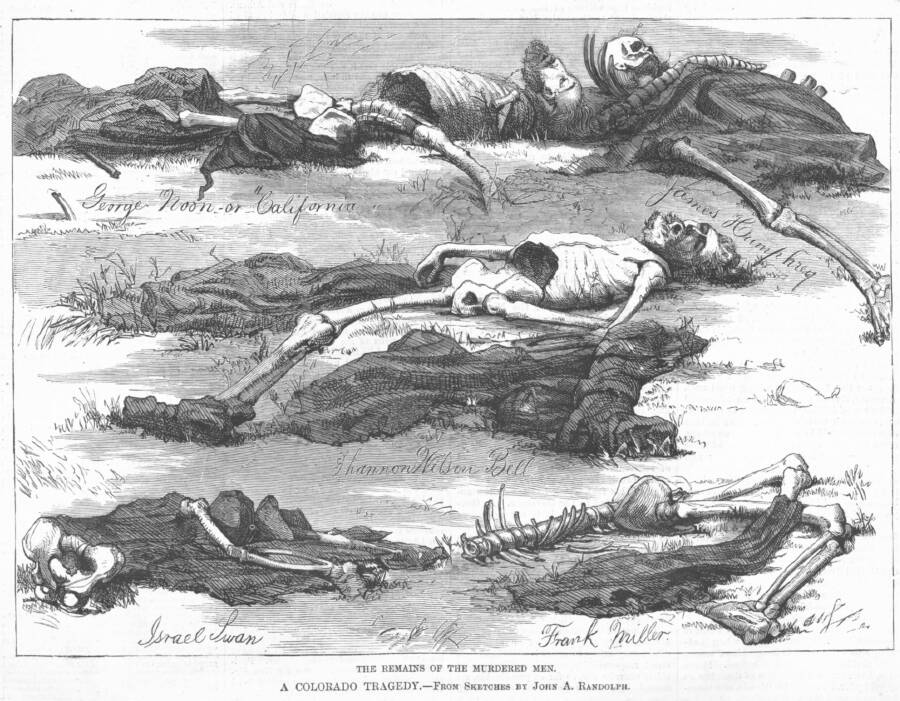

Though Packer was jailed in Saguache following this confession, he managed to escape some months later. Shortly afterward, the bodies of his companions were found in the mountains — not along the trail, as Packer had implied, but at a single campsite. Eerily, the remains of one, Swan, showed evidence that he’d fought for his life.

Public DomainAn illustration of Alfred Packer’s victims.

Nine years later, Packer was discovered living under an alias in Wyoming. Arrested again, Packer gave a second confession, but this time offered up a slightly different story. He claimed that he had left the camp to try to get a better vantage point, and that when he returned he found that Bell had gone insane and brutally murdered the others. When Bell charged him, Packer claimed he was forced to shoot him dead.

Then, Packer said he was forced to cannibalize the others in order to survive.

“I tried to get away every day but could not, so I lived off the flesh of these men the bigger part of the 60 days I was out,” he confessed.

Everett Collection Historical/Alamy Stock PhotoA photo of Alfred Packer during his incarceration at the Colorado Penitentiary, between 1886 and 1901.

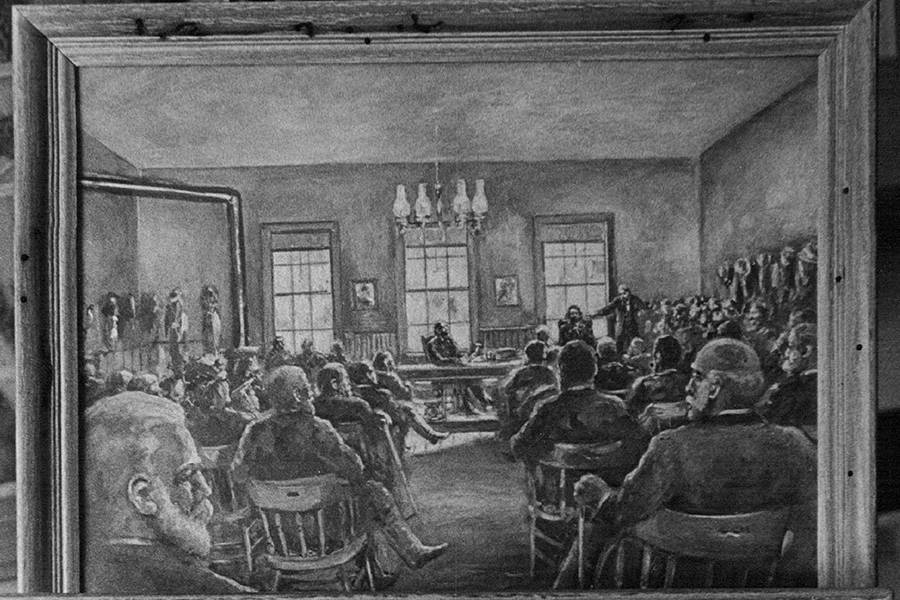

During his trial in April 1883, Alfred Packer repeated the story about Bell — and insisted that he turned to cannibalism only out of starvation.

“And right there was my last feeling,” Packer testified to the spell-bound court. “I gave up to it. I ate that meat, and it has hurt me for nine years. I was perfectly happy and can’t tell how long I remained there.”

Alfred Packer was subsequently found guilty of murdering Swan, and sentenced to die. As local papers reported at the time, the judge told Packer that he had “sowed the wind [and] must now reap the whirlwind” and that he would hang “by the neck until you are dead, dead, dead.”

However, that’s not how things went for Alfred Packer.

Alfred Packer’s Final Years And Gory Legacy

Denver Post Archives/Getty ImagesA portrait depicting the trial of Alfred Packer.

In the end, Alfred Packer never saw the gallows. His sentence was reversed by the Colorado Supreme Court in 1885 for being based on an ex post facto law, or a new law that retroactively changes the results of the law it replaces. As such, his charges were reduced to manslaughter and he was sentenced to 40 years in prison.

In 1901, however, after a campaign led by the Denver Post and reporter Polly Pry, Alfred Packer was paroled. After his release, Packer went to work as a guard at the Denver Post, a job he held until his death. He died of “trouble and worry” at the age of 65.

His last words were purportedly: “I’m not guilty of the charge.”

But though Alfred Packer is gone, the gory legacy of the “Colorado Cannibal” endures. In 1996, a black comedy musical was released, aptly titled Cannibal! The Musical, that details the fateful adventure. Perhaps more fitting, however, is the naming of a building after him at the University of Colorado, Boulder: the dining hall, known as the “Alferd Packer Restaurant & Grill.”

After learning about Alfred Packer, check out another crazy cannibal, like Issei Sagawa, who walks as a free man in Tokyo. Then, read about what human flesh probably tastes like, according to actual cannibals.