In the years leading up to World War II, Adolf Hitler designed a series of massive buildings and monuments that he planned to erect in Berlin after defeating the Allies, making the city the "capital of the world."

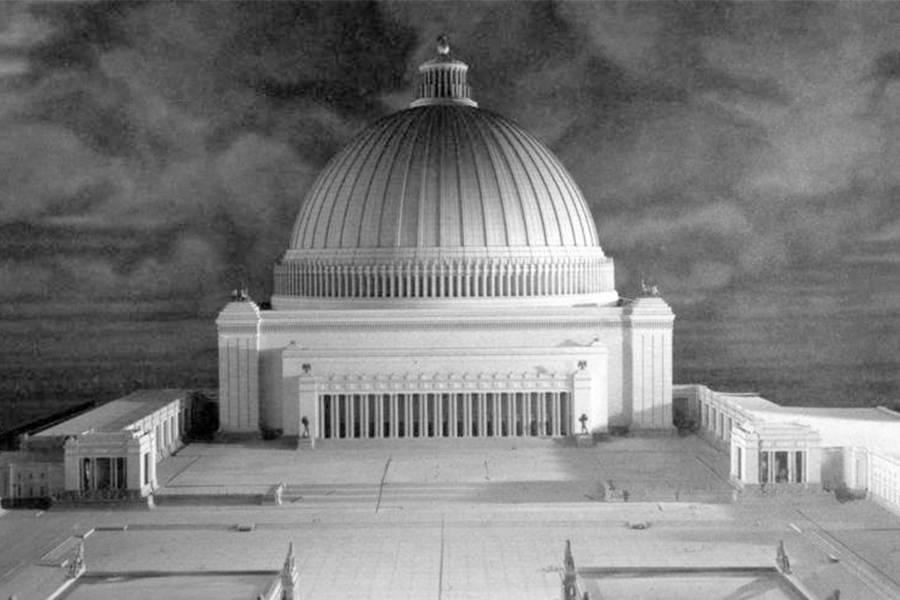

Bundesarchiv, Bild 146-1986-029-02/Wikimedia CommonsThe Volkshalle, the monstrous centerpiece of the planned Nazi super-city of Welthauptstadt Germania.

The alternative history series The Man in the High Castle takes viewers into a parallel universe where the Axis powers won World War II and Berlin is the capital of a sprawling German empire. Surprisingly, this Nazi super-city wasn’t born from the imaginations of filmmakers — it was the brainchild of Adolf Hitler himself.

In the years leading up to World War II, Hitler designed Welthauptstadt Germania, or “World Capital Germania.” He planned to raze much of Berlin and rebuild it as the center of his “Greater Germanic Reich.”

Some structures, such as a new Chancellery, were completed in time for Hitler to see his designs come to fruition. Others, like a grand Triumphal Arch that would tower over Paris’s Arc de Triomphe, never made it past the blueprints.

The Führer intended to win the war and force the Allies to provide money and labor for his massive project. However, when Hitler took his own life on April 30, 1945, his plans for Welthauptstadt Germania died with him.

The Origins Of Welthauptstadt Germania

Hitler may have started planning his World Capital as early as the mid-1920s, when he sketched out plans for a large arch that would honor the Germans who died during World War I. Within a decade, a scale model was under construction and engineers were working out how to feasibly build such large structures on Berlin’s marshy soil.

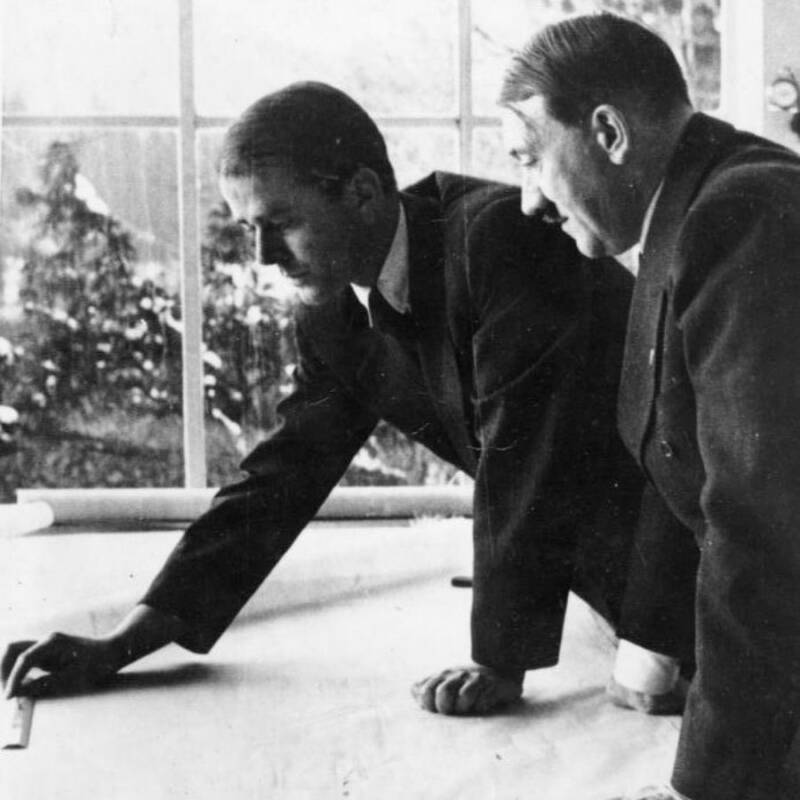

The Führer was assisted by Albert Speer, the “first architect of the Third Reich,” who aimed to bring Hitler’s ideas to life. Speer had impressed Hitler with his work on buildings in Nuremberg, which were deliberate reinterpretations of classical architecture into massive, distinctly austere Nazi structures designed to intimidate and overwhelm.

Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-V00555-3/Wikimedia CommonsAlbert Speer and Adolf Hitler together circa 1938.

Speer acted as the overseer of the project and produced many of the blueprints for the buildings Hitler had dreamed up. By the late 1930s, Speer had created a scale model of Welthauptstadt Germania, and laborers got to work making the city a reality. Hitler was determined for construction to be finished by 1950.

By 1939, the East-West Axis — a wide avenue lined with Nazi flags that ran from the Brandenburg Gate to a town square in the Charlottenburg district — was completed in time for Hitler’s 50th birthday celebration. Speer had moved the famous 19th-century Victory Column from its original location at the Reichstag government building to a central square in the middle of the avenue. This was ultimately one of the only Welthauptstadt Germania projects that was completed.

Another early project was the Schwerbelastungskörper, a gigantic concrete cylinder that represented just one of the four pillars that would be part of Hitler’s planned Triumphal Arch. Engineers erected this “exploration building” to determine if the ground could hold the weight of the monument. It ultimately sank more than seven inches in just three years, three times more than it should have. The pillar still stands in Berlin today as a grim reminder of what could have been.

The Unfinished Plans For Hitler’s World Capital

Adolf Hitler’s main goal for Welthauptstadt Germania was to make it the grandest city in the world. He wanted to build monuments that would outshine the greatest Europe had to offer. Most of them would be placed along a four-mile-long “Avenue of Splendors” that would cross the East-West Axis perpendicularly and serve as a parade ground.

At the south end would sit the Triumphal Arch. This arch was designed to dwarf the Arc de Triomphe in Paris, which would have been able to sit completely inside the opening of the new monument.

Sueddeutsche Zeitung Photo / Alamy Stock PhotoAdolf Hitler and other Nazi officials inspect a model of the Triumphal Arch.

At the north end, the boulevard would open up into a grand square surrounded by the most magnificent buildings in Welthauptstadt Germania. The only one of these structures that was completed was the New Reich Chancellery, a sprawling palace that was finished in 1939.

In his memoir, Inside the Third Reich, Albert Speer described what a visiting diplomat would see when entering the palace:

“By way of an outside staircase he first entered a medium-sized reception room from which double doors almost 17 feet high opened into a large hall clad in mosaic. He then ascended several steps, passed through a round room with a domed ceiling, and saw before him a gallery 480 feet long. Hitler was particularly impressed by my gallery because it was twice as long as the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles.”

On the north side of the plaza would stand the crowning jewel of Welthauptstadt Germania: the Volkshalle, or “People’s Hall.” It would have been the largest enclosed space in the world, able to hold 180,000 people at full capacity. The dome atop the building would be 660 feet high and 820 feet in diameter, some 16 times larger than the dome of St. Peter’s Basilica in Vatican City.

As Sascha Keil, a German spokesperson, told TIME in 2008, “With all 180,000 seats occupied, the condensed breath of the people would have accumulated in the dome and caused a rainfall.”

Bundesarchiv, Bild 146III-373/Wikimedia CommonsHitler’s scale-model of Welthauptstadt Germania, with the Avenue of Splendors connecting the Volkshalle, in the distance, to the Triumphal Arch, a gargantuan version of the Arc de Triomphe.

Workers never broke ground for the Volkshalle, and the Chancellery was destroyed by bombs in 1945.

Aside from the East-West Axis and the single pillar of the Triumphal Arch, hardly any other part of Welthauptstadt Germania was ever built. Much of the project would have consisted of new roads, autobahns, and residential areas. The environment would have been hostile to Berliners. Traffic lights and tramways would be a thing of the past, forcing pedestrians underground into a system of tunnels just to cross the roads.

The architecture would literally and metaphorically oppress its people. In fact, even though most of the city was never completed, the project still managed to oppress tens of thousands of Germans.

Welthauptstadt Germania: The Lasting Impacts Of The Nazi Super-City

Many believe that Kristallnacht, or the “Night of Broken Glass,” in November 1938 was the beginning of the Holocaust, but it actually started months earlier with the early stages of Welthauptstadt Germania’s construction.

Gross-Rosen, Buchenwald, and Mauthausen concentration camps were built near quarries, and prisoners at Sachsenhausen were forced to construct a massive brickworks. Speer signed a contract with the SS to have all bricks shipped to Berlin. Sachsenhausen was roughly 20 miles from Berlin’s center, so canals ferried the quarried stone to the Welthauptstadt Germania construction sites. Tens of thousands of people were worked to death at these camps to provide the material to build Hitler’s World Capital.

Then, there was the workforce needed to actually construct the buildings. In June 1938, the government ordered police to round up beggars off the street if they seemed fit to work. These men were then forced to perform heavy labor.

Dieter Brügmann/Wikimedia CommonsThe Schwerbelastungskörper, a concrete pillar built to see if Berlin’s marshy ground could hold the heavy foundation of the planned Triumphal Arch.

Hitler’s project was not without its critics. Speer’s number two, Hans Stefan, drew a series of caricatures that parodied the overbearing nature of the Germania project in secret, as reported by Der Spiegel in 2008. Several drawings poked fun at the ridiculous size of the Volkshalle. One cartoon depicts one of Berlin’s largest buildings, the Reichstag, being accidentally moved by a crane during the construction of the impossibly large hall.

Stefan did not hold back in criticizing the changes to Berlin, which he saw as tampering with German history and culture. After Hitler had the Victory Column relocated, Stefan’s response was to show the Goddess Victory, unhappy with Hitler’s decision, escaping via parachute from her fixture at the top of the monument.

Construction finally ground to a halt as World War II progressed. Speer believed that Nazi victory was imminent and remarked that Allied air strikes on Berlin had helped to level the old city to pave the way for Welthauptstadt Germania. They hadn’t.

Hitler died by suicide in April 1945, but Albert Speer got off much easier. At the Nuremberg Trials, he charmed the court, and despite his heavy use of concentration camp labor, he denied knowledge of the Holocaust. Spared execution, he spent the next 20 years in Spandau Prison.

After learning the history of Welthauptstadt Germania, take a look at these photos of everyday life in Nazi Germany. Then, go inside the Führerbunker where Adolf Hitler died.