Gods of death — like Anubis of ancient Egypt, the Norse deity Hel, and Mictlāntēcutli, the vicious ruler of the Aztec underworld — have played a key role in the cultures and religions of civilizations throughout history.

Death is a universal human experience. And ancient cultures around the world came up with different ways to interpret death, loss, and grief, often through myths about death gods.

Some of these gods were terrifying. The Maya believed that caves were portals to the underworld, which led to the creation of Camazotz, a bat-like deity. Likely modeled after the huge vampire bats that once lived in Central America, Camazotz was said to carry a knife in one hand and a human heart in the other. He was able to snatch his victims from the ground.

However, other death gods were more like judges than devils. Even Hades, often seen in popular culture as particularly satanic, was merely tasked with overseeing the underworld and making sure the dead got what they deserved. The Egyptian deity Anubis played a similar role, leading spirits to a scale where their heart would be weighed against a feather. If their heart was the same weight, they could advance to the afterlife.

Death gods like these helped ancient cultures interpret the pain of losing a loved one. And they often acted as a warning to the living to behave well in life, lest they face punishment in death.

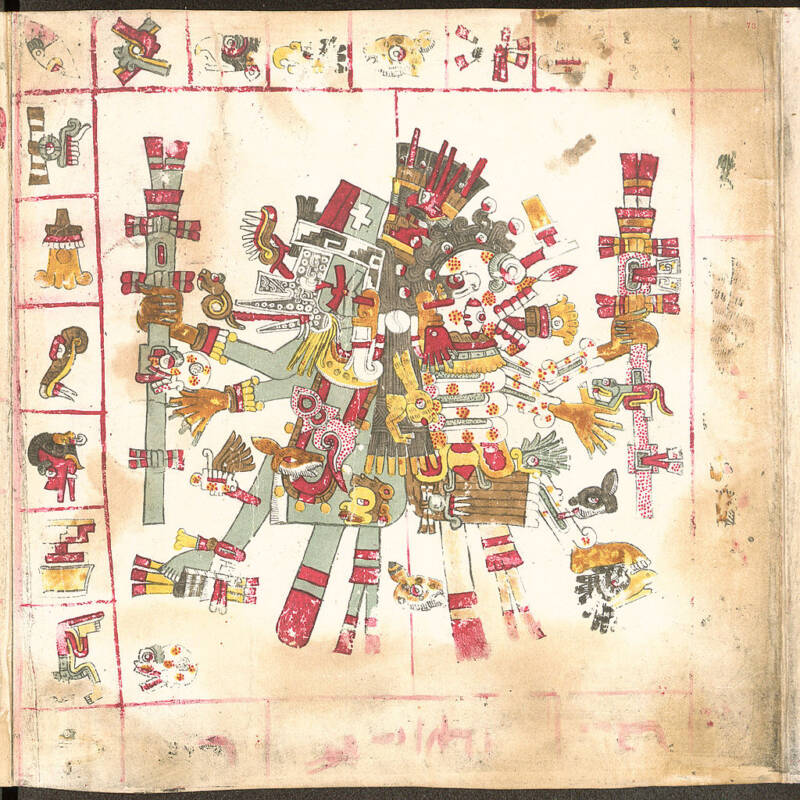

Mictlāntēcutli, The Aztec God Of Death

Public DomainMictlāntēcutli in the Codex Borgia.

The Aztecs believed that people went to different places after death depending on who they were and how they’d died. Children and innocents went to Cincalco, a paradise in a sacred cave. People who died in battle or were killed as sacrifices — alongside women who died in childbirth — went to a paradise known as Tonatiuhichan. Those killed by lightning strikes, drowning, or certain diseases went to a paradise called Tlalocan.

All others went to Mictlān, the deepest level of the Aztec underworld, which was ruled by the god of death, Mictlāntēcutli, and his wife, Mictēcacihuātl.

According to Aztec legend, Mictlāntēcutli and his wife lived in a windowless house replete with bats, owls, and spiders in the deepest pits of the underworld. There, Mictlāntēcutli acted as an arbiter of the dead who were sent to Mictlān. These people had to spend four years undergoing torturous tests involving obsidian knives, a void without gravity, and rivers that they could only cross if they had lived their lives in a certain way.

Those who reached the deepest parts of Mictlān would meditate on the states of consciousness until Mictlāntēcutli decided to allow them to atone for their wrongdoings in life. At that point, the Aztec god of death would reward them with eternal rest and transform their souls into nothingness.

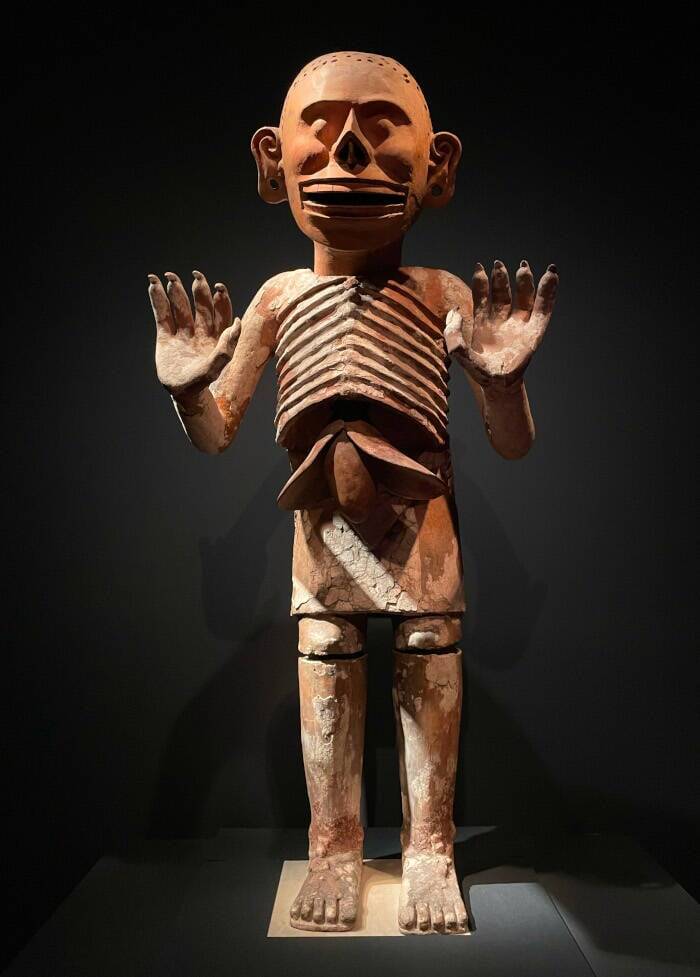

Templo Mayor Museum

A statue of Mictlāntēcutli, the Aztec god of death.

Death played an important role in Aztec culture, and Mictlantecuhtli did as well. Sacrifices were made to him every year, and, during the Spanish Conquest, the Aztec emperor Moctezuma II called for more sacrifices to Mictlāntēcutli in hopes of avoiding suffering in the underworld.

Indeed, Mictlāntēcutli was far from the only god of death to haunt the realms of early Mesoamerica.