Due to a loophole in Hitler's laws, Hans Massaquoi was able to survive as a black child in Nazi Germany. However, it wasn't easy.

Getty ImagesHans Massaquoi

He’d been called out to the schoolyard with his classmates for an announcement by the school’s principal. Herr Wriede announced to all of the children that the ‘beloved Fuhrer’ was there to talk to them about his new regime.

Like all of the other children in his class dressed in small brown Nazi uniforms with little swastika patches sewn onto the front, he was persuaded by the Nazi leaders charm and signed up for the Hitler Youth as soon as he could.

But, unlike all of the other children in his class, he was black.

Hans Massaquoi was the son of a German nurse and a Liberian diplomat, one of the few German-born children of German and African descent in Nazi Germany. His grandfather was the Liberian Consul in Germany, which allowed him to live among the Aryan population.

Hitler’s racial laws left a loophole, one Massaquoi was able to squeeze through. He was German-born, wasn’t Jewish, and the black population in Germany wasn’t big enough to explicitly codify in their racial laws. Therefore, he was allowed to live freely.

However, because he had escaped one form of persecution didn’t mean he was free from all of them. He wasn’t Aryan — far from it — so he never quite fit in. Even his request to join the Hitler Youth in third grade had been ultimately denied.

There were others that weren’t so lucky. After the 1936 Berlin Olympic Games, during which African-American athlete Jesse Owens won four gold medals, Hitler and the rest of the Nazi party began targeting black people. Massaquoi’s father and his family had to flee the country, but Massaquoi was able to remain in Germany with his mother.

But, at times, he wished he too had fled.

Wikimedia CommonsA Hitler Youth informational poster.

He began noticing that signs would crop up, forbidding “non-Aryan” kids from playing on swings or entering parks. He noticed Jewish teachers at his school were disappearing. Then, he saw the worst of it.

On a trip to the Hamburg Zoo, he noticed an African family inside a cage, placed among the animals, being laughed at by the crowd. Someone in the crowd saw him, called him out for his skin tone and publicly shamed him for the first time in his life.

As soon as the war began, he was almost recruited by the German Army but was luckily rejected after being deemed underweight. He was then classified as an official non-Aryan, and while not persecuted to the extent of the others, he was forced to work as an apprentice and laborer.

Once again, he found himself caught in the middle. While he was never pursued by the Nazis, he was never free from racial abuse. It would be a long time before he found his place in the world again.

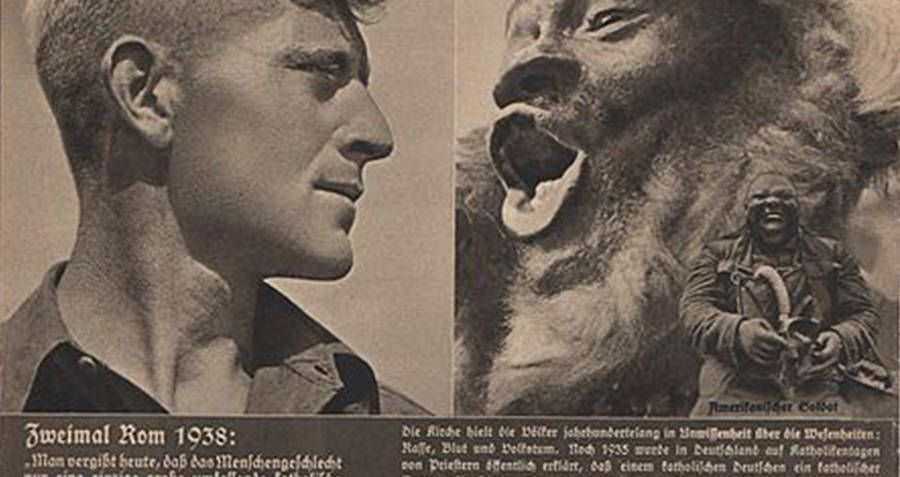

Wikimedia CommonsA racist Nazi propaganda poster comparing black people to animals.

After the war, Massaquoi began thinking about leaving Germany. He had met a man at a labor camp, a half-Jewish jazz musician who convinced him to work as a saxophonist at a jazz club. Eventually, Massaquoi emigrated to the United States to continue his music career.

On the way, he made a stop in Liberia to see his father, whom he hadn’t seen since his paternal family fled Germany. While in Liberia he was recruited to join the Korean War by the United States, where he served as a paratrooper for the American army.

After the Korean war, he made it to the United States and studied journalism at the University of Illinois. He worked as a journalist for forty years and served as a managing editor for Ebony, the legendary African-American publication. He also published his memoirs, titled Destined to Witness: Growing Up Black in Nazi Germany, in which he described his childhood.

“All’s well that ends well,” Hans Massaquoi wrote. “I’m quite satisfied with the way my life has turned out to be. I survived to tell the piece of history I was a witness of. At the same time, I wish everyone could have a happy childhood within a fair society. And that was definitely not my case.”

Enjoy this article on Hans Massaquoi? Next, read about the men who perpetuated Hitler’s rise to power. Then, take a look at these photos of life inside the Hitler Youth.