Afflicted with severe brain damage, Harolyn Suzanne Nicholas spent almost her entire life with caretakers or in mental institutions.

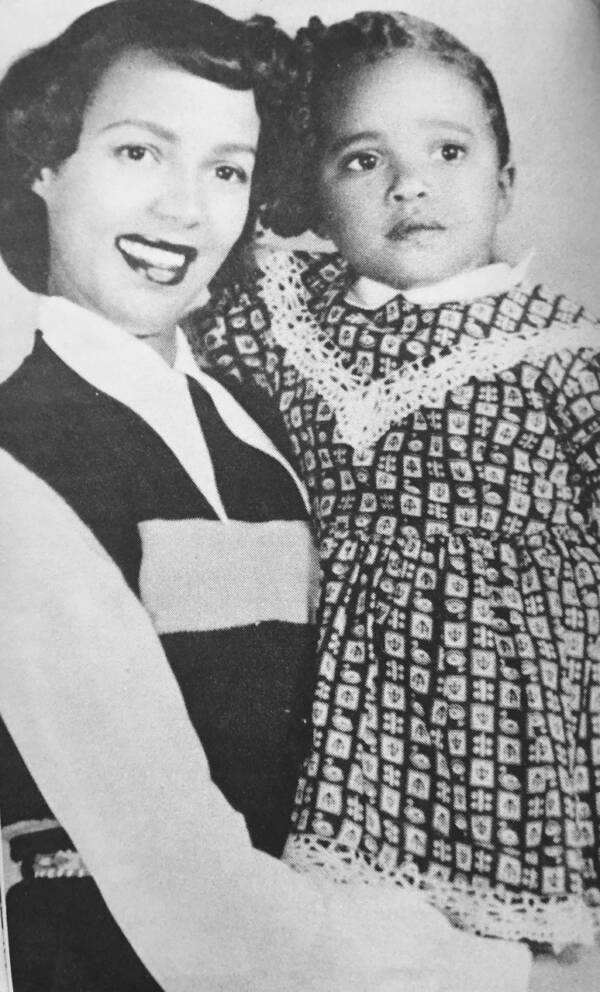

Twitter Harolyn Suzanne Nicholas with her mother, actress Dorothy Dandridge.

In 1963, Dorothy Dandridge made an appearance on The Mike Douglas Show. Beautiful, sophisticated, and the first Black actress to be nominated for a Best Actress Academy Award, she seemed to have it all. But on that day, Dandridge shared a sad secret she’d kept about her daughter, Harolyn Suzanne Nicholas.

“My daughter had a brain injury at birth,” Dandridge told the stunned studio audience. “I could sense that something was wrong when she was about two years old.”

She then told them the difficult and tragic story of her daughter, a story that remains largely unknown to this day.

The Traumatic Birth Of Harolyn Suzanne Nicholas

By 1943, Dorothy Dandridge was an up-and-coming young actress living in Los Angeles. Newly married to dancer Harold Nicholas and pregnant with her first child, she went into labor on Sept. 2 while at her sister-in-law’s house.

Dandridge wanted to go to the hospital, but her husband had taken the car to play golf. She delayed the birth — and later came to believe that doing so had cut off oxygen to Nicholas’ brain, resulting in permanent brain damage.

“Dottie never got over the overwhelming guilt she felt because she thought she was responsible for her child’s condition,” Geraldine Branton, Dandridge’s sister-in-law and close friend, explained to EBONY magazine. “She lived with that thought every day of her life. You could never convince her she wasn’t at fault.”

At first, however, Nicholas seemed like a healthy baby. It wasn’t until after the girl’s second birthday that Dandridge realized her daughter wasn’t developing as normal.

Harolyn Suzanne Nicholas’ Mental Disabiility

PinterestDorothy Dandridge on The Mike Douglas Show in 1963.

As Harolyn Suzanne Nicholas grew up, Dorothy Dandridge began to wonder if something was wrong with her daughter. When Nicholas was two years old, Dandridge told The Mike Douglas Show, “She couldn’t speak although other children her age were speaking.”

Other parents assured Dandridge that Nicholas would be fine. “People said, ‘Don’t worry, Einstein didn’t talk until he was six years old because he was a genius.'” But Dandridge continued to worry.

She took Nicholas to child psychoanalysts who suggested that Dandridge and her husband, who both traveled often for their work, had inflicted psychological damage on their daughter. Next, Dandridge took Nicholas to a doctor who scanned her brain and noticed something off.

“Mrs. Nicholas, your daughter has brain damage,” the doctor told Dandridge, adding, “The best thing for you to do is give her up and have another.”

Nicholas had a type of brain damage called cerebral anoxia. “[That] means she had an asphyxiated condition at birth,” Dandridge explained.

Sadly, it also meant that Harolyn Suzanne Nicholas would have a complicated life.

“[Nicholas] has no conception of time,” Dandridge said. “She doesn’t even know that I’m her mother. She only knows that she likes me and I like her and she feels warmth and that I’m a nice person.”

Dandridge decided that it would be best for Nicholas to live with a caretaker. But she was heartbroken and haunted by giving her daughter up.

“On the outside I said to myself, ‘I’ve had it, I’ll give her up,'” Dandridge later said. “Inside I never gave her up. It was myself that I began giving up.”

The Sad Fate Of Dorothy Dandridge’s Daughter

Convinced by doctors to give her daughter up, Dorothy Dandridge placed Harolyn Suzanne Nicholas with a caretaker. Then, her star began to rise — even as her personal life crumbled.

“If it is possible for a human being to be like a haunted house,” Dandridge wrote in her autobiography, “maybe that would be me.”

Though celebrated as an actor — Dandridge was nominated for Best Actress for her role in Carmen Jones (1954) — she struggled with racism and her relationships. She divorced Harold Nicholas and her second husband, Jack Denison. And when she went bankrupt in 1963, the sometimes violent Harolyn Suzanne Nicholas was “dumped” back on Dandridge’s doorstep after she failed to pay the bill for her daughter’s private care.

With no money to care for Nicholas, Dandridge was forced to commit her daughter to a state institution. “She should be placed where she can be best cared for,” Dandridge said.

But Dorothy Dandridge wouldn’t be there to make sure Nicholas got the attention she needed. On Sept. 8, 1965, about a week after Nicholas’ 22nd birthday, Dandridge was found dead of an accidental overdose in Hollywood. According to Biography, she had just two dollars left in her bank account.

Nicholas remained institutionalized and died in 2003 at the age of 60. But she was, in Dorothy Dandridge’s life, both a source of great pride and great pain.

“She’d hug me tight, crushing into my breasts,” Dandridge wrote. “I have known quite a few men, since then, but I tell you, you cannot get that feeling from anything else in the world. Except this: I knew that to everyone else she was hideous.”

After reading about Harolyn Suzanne Nicholas, see why Lana Turner’s daughter Cheryl Crane stood trial for murder at the age of 14. Or, discover the tragic story of Theodosia Burr, Aaron Burr’s daughter.