In 1861, Harriet Jacobs published Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl about the sexual harassment and abuse she faced as an enslaved woman in the antebellum South and her brave escape to the North.

Public DomainThe only known photograph of Harriet Jacobs, taken in 1894.

For much of the 20th century, the book Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Written by Herself was thought to be a 19th-century work of fiction about the life of an enslaved woman written by a white female author. In fact, the harrowing story of sexual abuse and escape was written by Harriet Jacobs, a real enslaved woman who escaped to the North in the 1840s.

Jacobs was not only one of the few enslaved women to write about her experience, she was also among the first to detail the sexual oppression she faced at the hands of white men. “Slavery is terrible for men,” Jacobs wrote, “but it is far more terrible for women.”

After making her escape, Harriet Jacobs became involved with the abolitionist movement, even working above the office of Frederick Douglass’ North Star newspaper. Friends she met during this time encouraged her to write down her story, and she published Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl in 1861.

However, after the Civil War ended, Jacobs’ book faded into obscurity. It wasn’t until the civil rights movement of the 1960s that it gained traction once more, and after its reprint in 1973, it became one of the leading slave narratives from the era. And behind it all was a brave woman who had risked everything to save herself, her children, and countless other women abused by their enslavers.

The Dangerous Life Of An Enslaved Girl

Born in 1813 or 1815 in Edenton, North Carolina, Harriet Jacobs spent much of her childhood sheltered from the harsh realities of American slavery.

“[We] lived together in a comfortable home,” she wrote in her autobiography, which was published in 1861, “and, though we were all slaves, I was so fondly shielded that I never dreamed that I was a piece of merchandise.”

Even after her mother’s death, Jacobs was cared for by her enslaver’s wife, who taught her how to read, write, and sew. But when this woman died in 1825, Jacobs was sent to Dr. James Norcom.

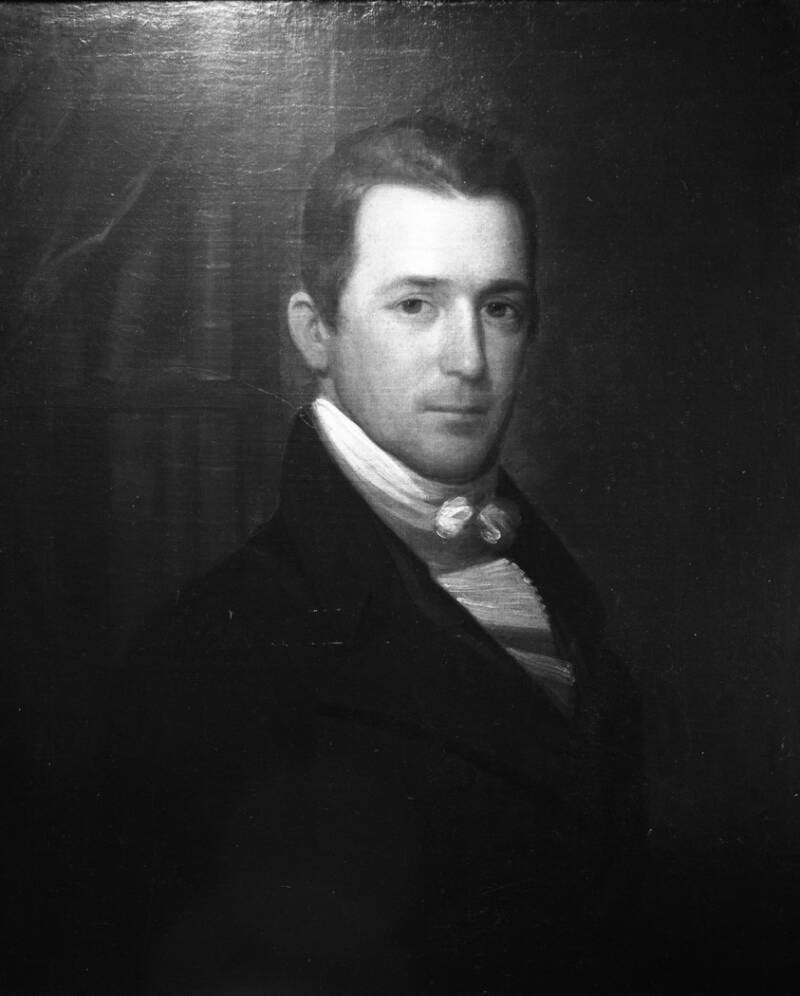

State Archives of North CarolinaJames Norcom, the white doctor who sexually harassed Harriet Jacobs for years.

Around the time Jacobs turned 15, Norcom began to sexually harass her. He whispered “foul words” in her ear, vehemently refused to let her marry a free Black man, and pressured her to have sex with him. Jacobs steadfastly refused. When she learned that Norcom was building a cottage for her four miles outside of town, however, Harriet Jacobs knew that she would have to resort to more extreme measures to escape his advances.

She turned to a white lawyer she knew, Samuel Tredwell Sawyer. Sawyer was kind, friendly, and in a position of power. (The New York Times reports that he was related to two governors of North Carolina and later became a congressman.) Jacobs entered into a sexual relationship with him partly out of attraction and partly out of hopes that he would protect her.

“It was something to triumph over my tyrant in that small way,” Jacobs wrote, adding: “I was sure my friend would buy me.”

But even when Harriet Jacobs got pregnant — she and Sawyer ultimately had two children together, Joseph and Louisa — Norcom refused to sell her. And when she got wind that Norcom was planning to send her and her children to work on a plantation, she decided it was time to escape.

Harriet Jacobs’ Escape To The North

Harriet Jacobs’ escape from North Carolina would ultimately take several torturous years. In 1835, she went into hiding, first at various neighbors’ homes, then into a tiny crawlspace in her grandmother’s attic. The crawlspace was small — nine feet long, seven feet wide, and three feet high — and populated by insects and vermin. It was freezing in the winter and sweltering in the summer. But it was preferable to Norcom’s presence, and Jacobs would ultimately spend nearly seven years in hiding there.

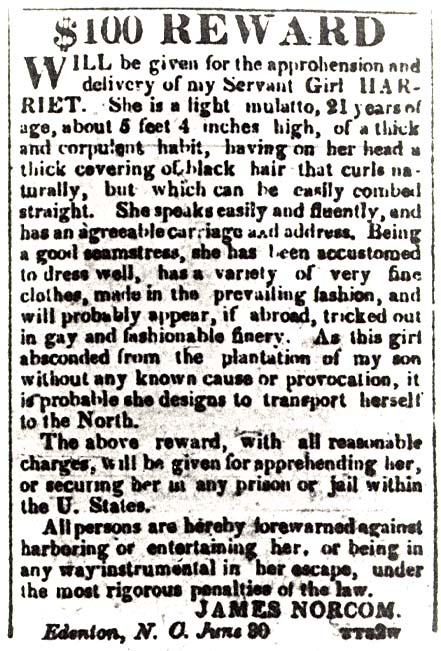

Public DomainA runaway slave notice about Harriet Jacobs, posted by her tormentor James Norcom.

Her situation was made slightly more bearable by the fact that Sawyer was able to purchase their children, Joseph and Louisa. After drilling a hole in the wall, Jacobs often watched them play in the front yard.

Finally, in 1842, Harriet Jacobs was able to leave the crawlspace.

Both her children had been sent North, and Jacobs went first to Philadelphia, then to New York City, and finally to Rochester. Her brother, who was also a fugitive, lived there, and the two of them became involved with abolitionists who published Frederick Douglass’ paper, The North Star.

Two abolitionists, Nathaniel Parker Willis and his wife Cornelia Grinnell Willis, were eventually able to purchase Jacobs’ freedom. And another, Amy Post, encouraged Jacobs to write her own story. Jacobs was reluctant at first, but she eventually agreed to write about her enslavement to appeal to the sympathies of white women in the North.

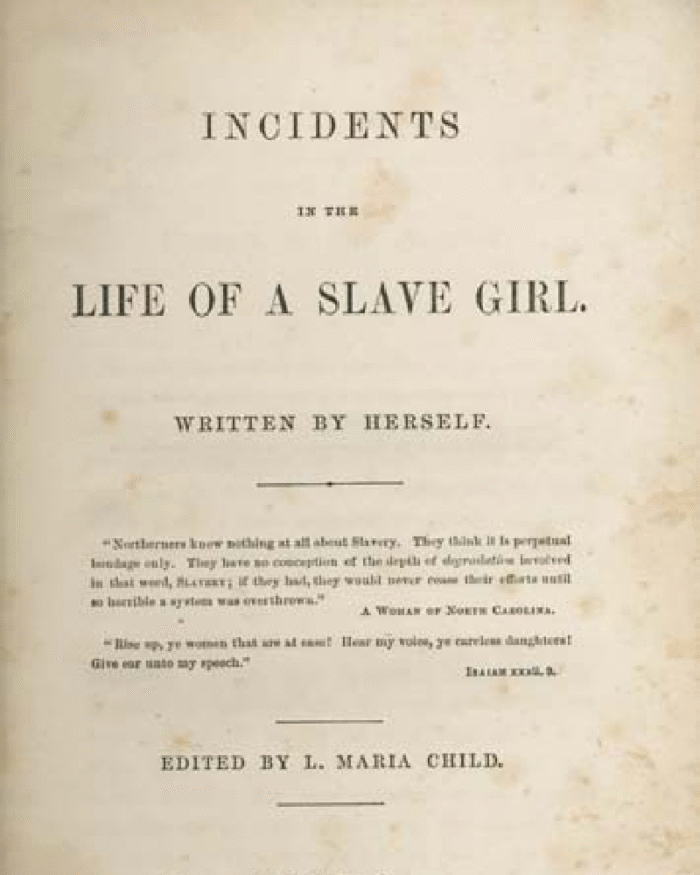

Public DomainThe first edition of Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl.

She wrote Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Written by Herself between 1853 and 1858 under a pen name, Linda Brent. Jacobs changed other names as well: Dr. James Norcom became “Dr. Flint,” and Samuel Tredwell Sawyer became “Mr. Sands.” The book was published in 1861 with the help of a white female editor, abolitionist Lydia Maria Child.

“I do earnestly desire to arouse the women of the North to a realizing sense of the condition of two millions of women at the South, still in bondage, suffering what I suffered, and most of them far worse,” Jacobs wrote. “I want to add my testimony to that of abler pens to convince the people of the Free States what Slavery really is. Only by experience can any one realize how deep, and dark, and foul is that pit of abominations.”

The book was well-received among abolitionists — but it was swiftly overshadowed by the growing conflict of the Civil War.

How Harriet Jacobs Was Forgotten — Then Rediscovered A Century Later

State Archives of North CarolinaA drawing of Harriet Jacobs.

Harriet Jacobs played an active role during and after the Civil War. During the war, she moved to Washington, D.C. to nurse Black soldiers and to help recently freed slaves. And both during the conflict and afterward, Jacobs and her daughter threw themselves into relief work.

Little is known about her later years, however. Harriet Jacobs died on March 7, 1897, in Washington D.C. She was buried at Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Her book was largely forgotten until the 1960s, when it resurfaced during the American civil rights movement. But even then, most people thought that Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl was a work of fiction written by the white woman listed as its editor, Lydia Maria Child.

Mount Auburn CemeteryHarriet Jacobs’ grave, alongside the grave of her daughter, at Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

It wasn’t until the 1980s that a scholar named Jean Fagan Yellin discovered the truth. While working on her dissertation, Yellin came across the book and noticed that Child was listed as the editor. Suspecting that the work might be an autobiography written by a former slave, Yellin researched it further — and was able to confirm that it had been written by Harriet Jacobs.

Today, Harriet Jacobs’ book is considered one of the most important slave narratives of its time. Not only does it offer a harrowing look at the realities of American slavery, but it’s also written from the rare perspective of an enslaved woman. By telling her story, Jacobs was able to shed light on the undiscussed realities of sexual abuse that haunted women like her across the South.

After reading about Harriet Jacobs, go inside the surprisingly complicated question of when slavery actually ended in the United States. Or, discover the little-known story of William Still, the heroic “Father of the Underground Railroad” who helped some 800 enslaved people escape to freedom.