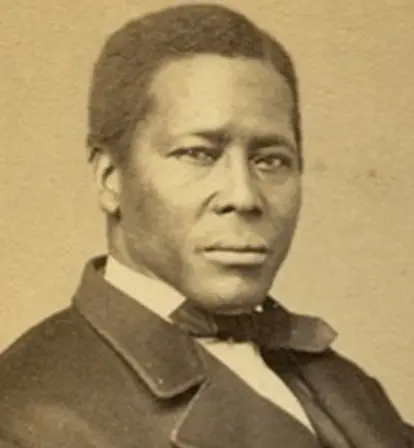

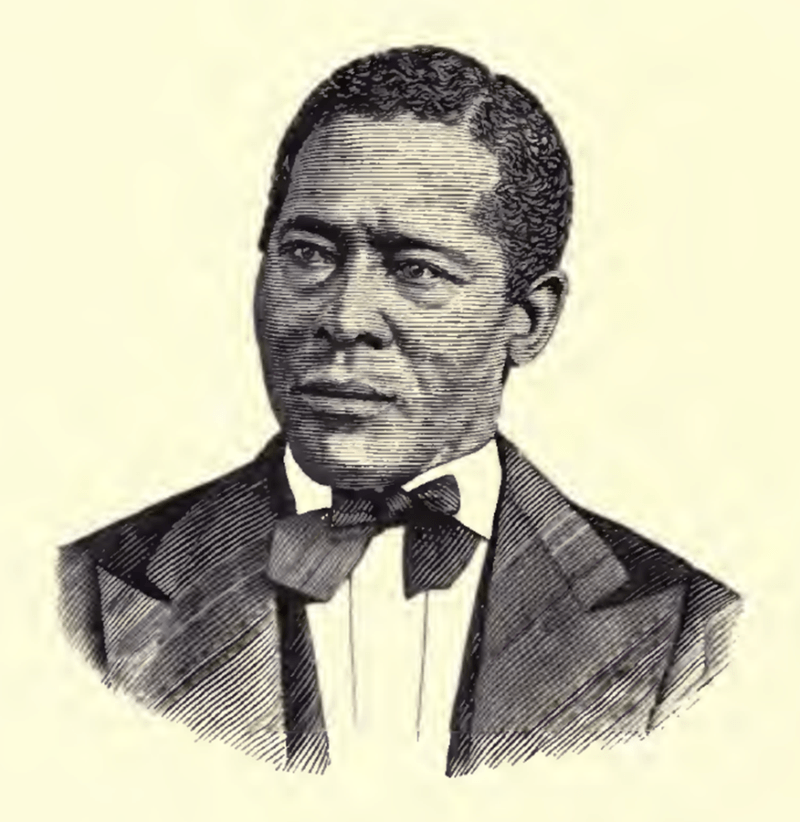

William Still helped some 800 slaves escape to freedom, but his heroism is often overshadowed by Harriet Tubman's.

Swarthmore CollegeWilliam Still was a free-born black abolitionist who was pivotal in rescuing hundreds of black slaves through the Underground Railroad.

William Still was known as the “Father of The Underground Railroad,” aiding perhaps 800 fugitive slaves on their journeys to freedom and publishing their first-person accounts of bondage and escape in his 1872 book, The Underground Railroad Records. He wrote of the stories of the black men and women who successfully escaped to the Freedom Land, and their journey toward liberty.

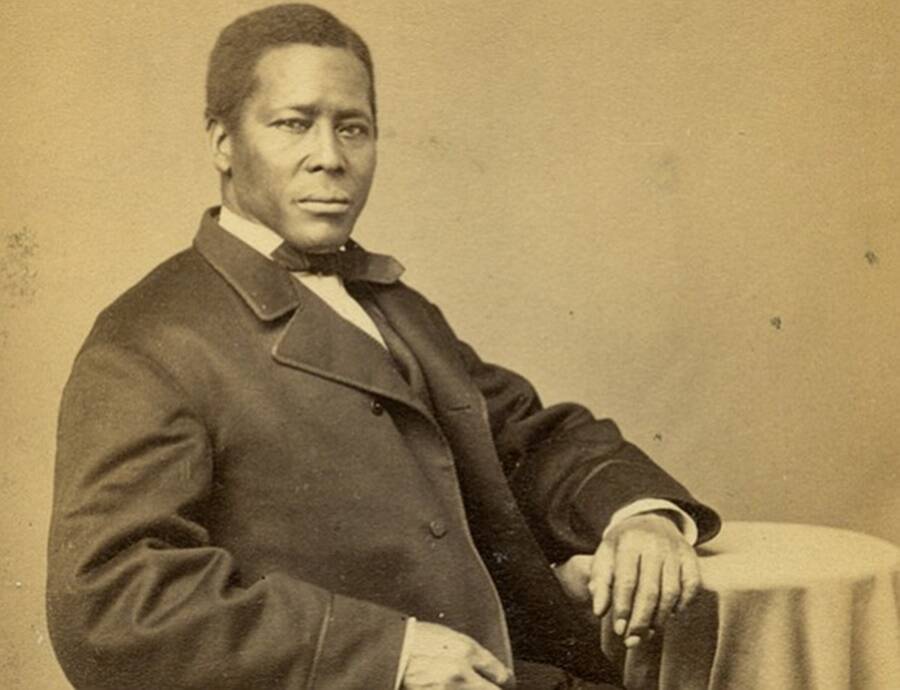

The Underground Railroad

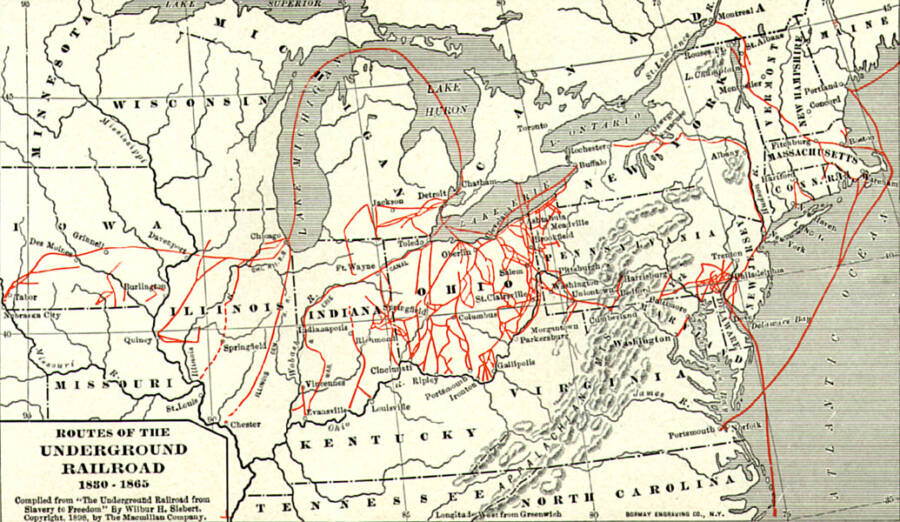

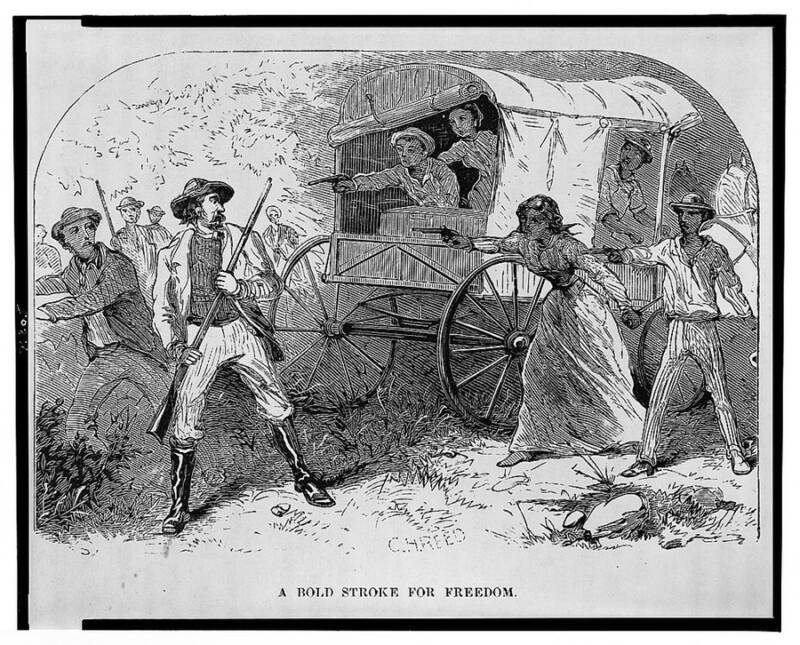

Wikimedia CommonsThe Underground Railroad began to take shape toward the early 18th Century, providing safe routes and aid for escaped slaves.

The Underground Railroad was an organized network consisting of black and white abolitionists who helped runaway slaves find food, shelter, and safe passage during their escape. There were homes and businesses which secretly became “stations” along the route toward the north, harboring fugitive slaves temporarily before they could move on to the next safe place.

Those who helped escaped slaves move from station to station, like Harriet Tubman, were known as “conductors.” William Still, meanwhile, was a “station master.”

It’s difficult to pinpoint when the movement began but scholars estimate the loose network of abolitionists started to take shape toward the end of the 18th century.

In 1786, George Washington, who owned hundreds of slaves in his lifetime, complained about a “society of Quakers” helping his runaway slaves, (many white Quaker abolitionists were part of the Underground Railroad). On November 20 of that same year, after one of his slaves escaped, he wrote that it “is not easy” to apprehend fugitive slaves “when there are numbers who would rather facilitate the escape of slaves than apprehend them when runaways.”

The freedom network became known as the Underground Railroad decades later, in around 1831.

The Underground Railroad was a vital asset in helping escaped slaves make their way safely through the dangerous route from the South to the North, where by the early 1800s most states had abolished slavery.

The journey grew longer in 1850, when Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act. The law required that all escaped slaves be returned to their masters; officials who failed to return apprehended slaves faced a fine equivalent to tens of thousands of dollars today. And so the Underground Railroad was forced to extend up to Canada, which outlawed slavery in 1834. There was also arms of the Railroad that went from the southernmost states to Mexico and the Caribbean.

Wikimedia CommonsWilliam Still’s first time helping a slave on the run was when he was a young boy, and continued to aid countless others since.

“The heroism and desperate struggle that many of our people had to endure should be kept green in the memory of this and coming generations.”

According to one estimate, approximately 100,000 slaves were aided by the Underground Railroad by 1850. The network was an important part of American history that would have likely been buried by time if it weren’t for the neatly-kept records of the network’s activities, penned by none other than William Still.

William Still: Abolitionist

Wikimedia CommonsHe used his literacy as a form of resistance and later published a book about the Underground Railroad’s work.

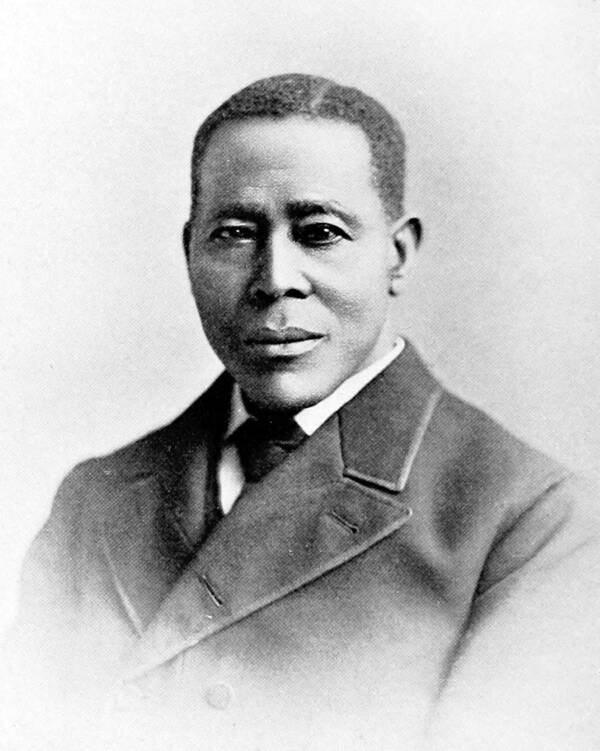

Born free on Oct. 7, 1821, in Burlington County, New Jersey, William Still was the youngest of 18 children.

His parents, Levin and Sidney (who later changed her name to Charity) Still, were both escaped slaves from Maryland. His mother had to escape twice, after she was found and captured the first time. For her second escape attempt, she was forced to leave behind two of her four children. The two sons she left behind were later sold to slave owners in the Deep South.

Library of CongressAn illustrated page from William Still’s book.

William Still received some schooling, and inherited a strong work ethic and family values from his parents. In 1844, at age 23, he moved to Philadelphia and became a janitor for the Pennsylvania Society for the Abolition of Slavery (PSAS). In 1847, he rose to the position of clerk, and that same year he married Letitia George. They had four children.

As he grew older and more successful as a businessman, starting a coal delivery business, Still emerged as a leader of Philadelphia’s black community. In 1852 he became chair of PSAS’s Vigilance Committee, aiding fugitive slaves passing through the city on the Underground Railroad.

Under Still’s supervision, the committee was instrumental in financing groups of former slaves for their journeys up north, even funding several of Harriet Tubman’s rescue expeditions. He personally provided food and shelter to many of the runaway slaves, too.

Historians believe Still rescued somewhere near 800 slaves through his work with the Underground Railroad, earning him the title, “Father of the Underground Railroad.”

Still Kept Records Of The Underground Railroad’s Activities

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M5KTKrvErko

One of William Still’s most impressive achievements was teaching himself to read and write. Using what little schooling he had, Still studied by reading everything under the sun. His literacy proved to be a potent weapon against American slavery and racism.

In 1859, he penned a letter to the press decrying the racial discrimination in Philadelphia’s streetcars, and in 1867 he expanded on that letter in a self-published book titled, A Brief Narrative of the Struggle for the Rights of Colored People of Philadelphia in the City Railway Cars.

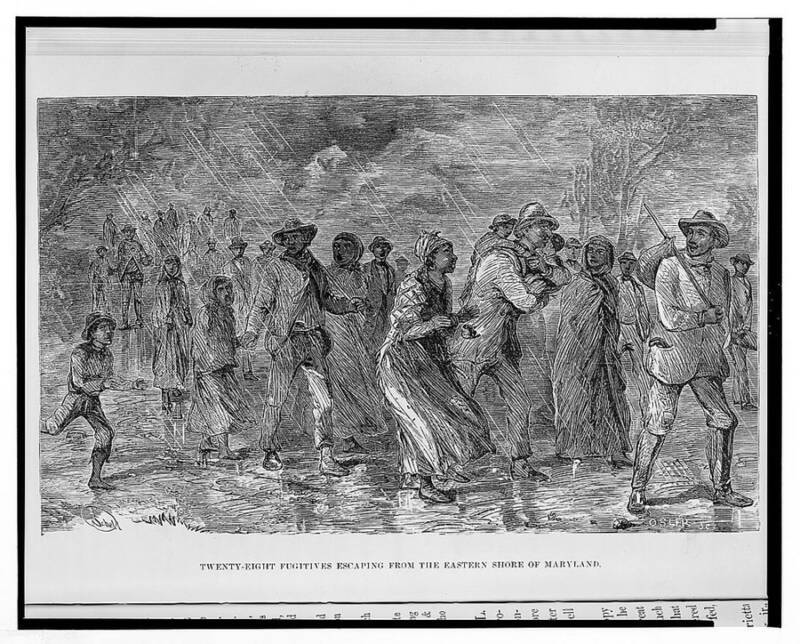

Library of CongressThe Underground Railroad network was instrumental to the freedom of at least 100,000 Black slaves.

But well before then, Still began to document the lives and tragedies of the hundreds of escaped slaves he encountered in Philadelphia.

“It was my good fortune to lend a helping hand to the weary travelers flying from the land of bondage,” he wrote of his service to the freedom movement.

In one particularly astounding example, he interviewed an escaped slave named Peter who turned out to be his own brother. “Being directed to the Anti-Slavery Office for instructions as to the best plan to adopt to find out the whereabouts of his parents,” Still wrote, “fortunately he fell into the hands of his own brother, the writer, whom he had never heard of before, much less seen or known.”

Peter lived more than 40 years in slavery before fleeing to Indiana, with the help of white abolitionist Seth Concklin, and then venturing to find his childhood home in New Jersey. That’s when he encountered his long-lost brother, William.

In 1872, William Still published The Underground Railroad Records. It was the only first-person account of activities on the Underground Railroad that was written and published by an African American. His book was exhibited at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition years later.

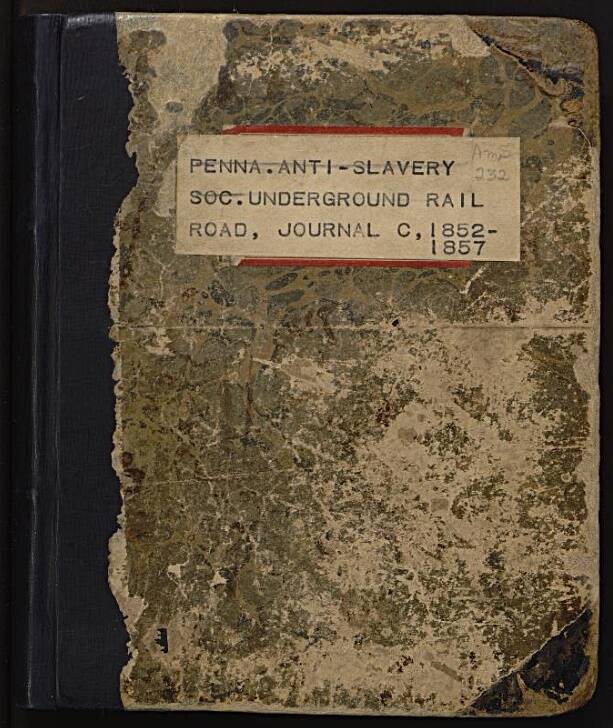

Historical Society of PennsylvaniaWilliam Still wrote about the men and women he encountered and the secret operations of the movement in great detail in his journals.

William Still’s records of the Underground Railroad have proven to be a vital source of history, an enduring body of evidence of the perseverance of black Americans in their struggle for freedom. It is also the only existing collection of documents about the freedom network.

Much of his papers are now kept in the Charles L. Blockson Afro-American Collection at Temple University in Philadelphia. The papers, which span between 1865 and 1899, contain 140 letters and 14 photographs related to the Still family. And just like the Underground Railroad, the memory of his role in the success of the freedom network must be never be forgotten.

Now that you’ve learned the little-known story of black abolitionist William Still, read about Juneteenth, the yearly celebration of African American emancipation from slavery in the U.S. Then, meet the Harlem hellfighters, the overlooked black heroes of World War I.