After crossing the Mason-Dixon line on foot, Harriet Tubman went back to guide dozens of slaves to freedom via the Underground Railroad — and freed hundreds more as a spy for the Union Army.

In the wee hours of June 2, 1863, Harriet Tubman — already world-weary from rescuing dozens of slaves in Maryland — guided Union boats around “torpedo” mines along South Carolina’s Combahee River.

It was a difficult time for the Union Army, to say the least. Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee had just won his greatest victory of the war a month prior in the Battle of Chancellorsville — an embarrassing loss for the Union to an army half its size.

But the Union had a secret weapon: Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation in January served as an open invitation for Southern slaves to join its ranks — if they could manage to escape.

For this purpose, the Union had another secret weapon: Harriet Tubman.

When Tubman’s boats reached the shores of the Combahee, the scene erupted in chaos. Escaped slaves were clamoring to get a spot on the rowboats to freedom. “They wasn’t coming and they wouldn’t let any body else come,” Tubman recalled.

That’s when a white officer suggested Tubman should sing. And sing she did:

“Come along; come along; don’t be alarmed

For Uncle Sam is rich enough

To give you all a farm.”

The crowd calmed, and 750 slaves were saved.

It was the largest liberation of slaves in American history. But it was all old hat to Tubman, for she had been the most prolific “conductor” on the Underground Railroad for more than a decade.

Born Into Bondage

The person history has remembered as Harriet Tubman was actually born Araminta Ross in around 1822 in Dorchester County, Maryland, on the state’s eastern shore. Her family called her “Minty.”

Her parents, Harriet Green and Ben Ross, had nine children, of which Tubman was the fifth. Tubman was born into slavery, and her owner, a farmer named Edward Brodess of Bucktown, Maryland, rented her out as a nursemaid for a different family when she was only about six years old.

Wikimedia CommonsHarriet Tubman was forced to work from age six. When she was 13, a white overseer struck her in the head and gave her a lifelong brain injury.

Brodess made $60 a year from renting her out – but young Harriet Tubman paid the price.

It was her job to stay up all night to make sure a baby wouldn’t cry and wake its mother. If Tubman fell asleep, the mother would whip her. On cold nights, Tubman would stick her toes into the smoldering ashes of a fireplace to keep from getting frostbite.

“She talked about how lonely and sad she was when she was separated from her mother, and how she would cry herself to sleep at night,” said Tubman’s biographer, Kate Clifford Larson.

When the white family, headed by James Cook, felt particularly cruel, they put her on muskrat trap duty. According to Harriet Tubman, Moses of Her People, an 1886 biography written by Sarah Hopkins Bradford and based on extensive interviews with the former slave, Tubman was once sent to check the traps and wade through icy water when she was sick with the measles.

The couple, either after their own frustration with Tubman or after Tubman’s mother urged her owner to release her daughter from the Cooks, eventually gave the girl back to Brodess.

At age 13, Tubman was nearly killed by a blow to the head. Walking into the Bucktown Village Store just as an angry white overseer was trying to catch a runaway slave, she stood in a doorway to keep the overseer from chasing after him. The man grabbed a two-pound weight from the store counter, aiming to throw it at the fugitive behind her, but instead it hit Harriet Tubman square in the head.

“The weight broke my skull,” she later recalled. “They carried me to the house all bleeding and fainting. I had no bed, no place to lie down on at all, and they laid me on the seat of the loom, and I stayed there all day and the next.”

The injury plagued Tubman with a lifetime of narcolepsy and severe headaches. According to National Geographic, it also gave her wild dreams and visions that made her extremely religious.

She did recover — but she never forgot that day.

Harriet Tubman Escapes Slavery

It was 1844, and Harriet Tubman remained a slave — even after informally marrying John Tubman, a free black man. At this point, she had become one of the only female slaves to labor in the forests on a timber gang, familiarizing herself with the woods and swamps of Maryland, and hearing whispers of the Underground Railroad from the men who operated ships along the rivers and creeks.

Wikimedia CommonsThe farm in Maryland where Harriet Tubman was enslaved.

As Larson put it in Bound for the Promised Land, “these black men were part of a larger world, a world beyond the plantation, beyond the woods…ranging as far away as Delaware, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey. They knew the safe places, they knew the sympathetic whites, and, more important, they knew the danger.”

Tubman herself was placed in greater danger when her master, Edward Brodess, died suddenly in 1849. The word was that his small farm was deeply in debt, and slaves feared his widow would sell them for cash — perhaps to plantations down south. He had done as much to three of Tubman’s sisters about a decade earlier.

Being a slave in Maryland was bad enough, but word was the plantations down south were much more horrific.

“For I had reasoned dis out in my mind; there was one of two things I had a right to, liberty, or death; if I could not have one, I would have de oder; for no man should take me alive; I should fight for my liberty as long as my strength lasted, and when de time came for me to go, de Lord would let dem take me.”

This, Tubman knew, was her moment — Brodess was gone, the farm was disorganized, and she had nothing to lose. That fall, she and two of her brothers tried to escape but turned back. Soon after, she went alone, walking 90 miles through forests and marshes and under constant threat of capture until she reached Pennsylvania.

“I looked at my hands to see if I was the same person,” Tubman later told Bradford, about her first moments in a free state. “Now I was free. There was such a glory over everything, the sun came like gold through the trees, and over the fields, and I felt like I was in heaven.”

A Conductor On The Underground Railroad

Almost as soon as she achieved her own freedom, Harriet Tubman vowed to return to Maryland for her family and friends. She spent the next decade of her life making 13 trips back, ultimately freeing 70 people from the bonds of slavery.

Armed with a small rifle, Tubman used the stars and the navigational skills she learned while working in the fields and woods to safely transport slaves from the South across the Mason-Dixon line.

Famous abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison would later dub Tubman “Moses” for her ability to navigate the backwoods so intuitively and keep her proverbial flock out of harm’s way. The name stuck, because he was right: Tubman later claimed she never lost a single soul on her travels.

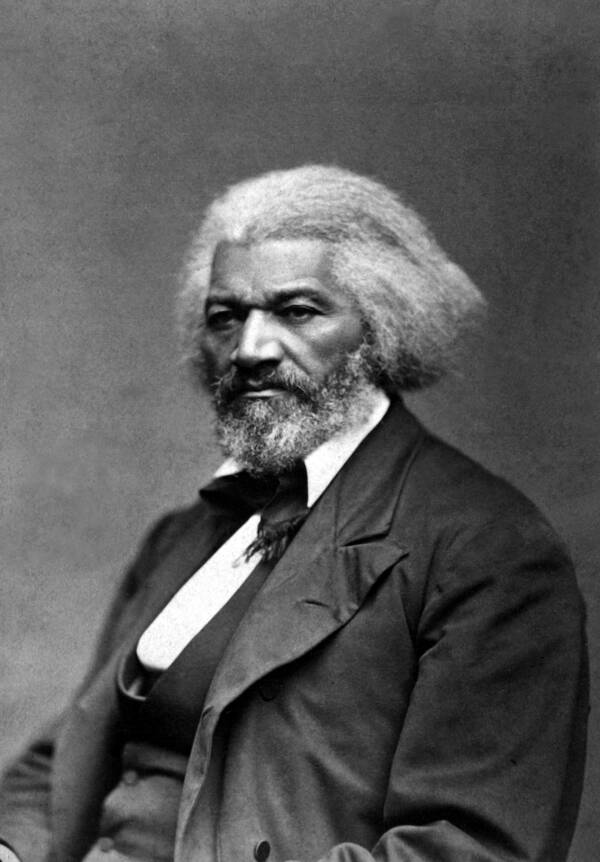

Wikimedia CommonsPortrait of Frederick Douglass, ca. 1879. He and Tubman became close friends and collaborators.

Tubman helped her first group of slaves, comprised of her sister and her family, escape in 1850. She had them board a fishing boat in Cambridge that sailed up the Chesapeake Bay and led them to Bodkin’s Point. From there, Tubman guided them from safehouse to safehouse until they reached Philadelphia.

In September, Tubman officially became a “conductor” of the Underground Railroad. She was sworn to secrecy, and focused her second trip on rescuing her brother James and various friends, whom she guided to the home of Thomas Garrett — the most famous “stationmaster” who ever lived.

Tubman started freeing slaves at the very moment it became much more dangerous. In 1850, the Fugitive Slave Act was enacted, allowing for both fugitive and free slaves in the north to be captured and re-enslaved. It also made it illegal for anyone to help an escaped slave. If one saw a runaway and didn’t detain them until authorities could deport them back to the “rightful” owner in the South, hefty punishment loomed.

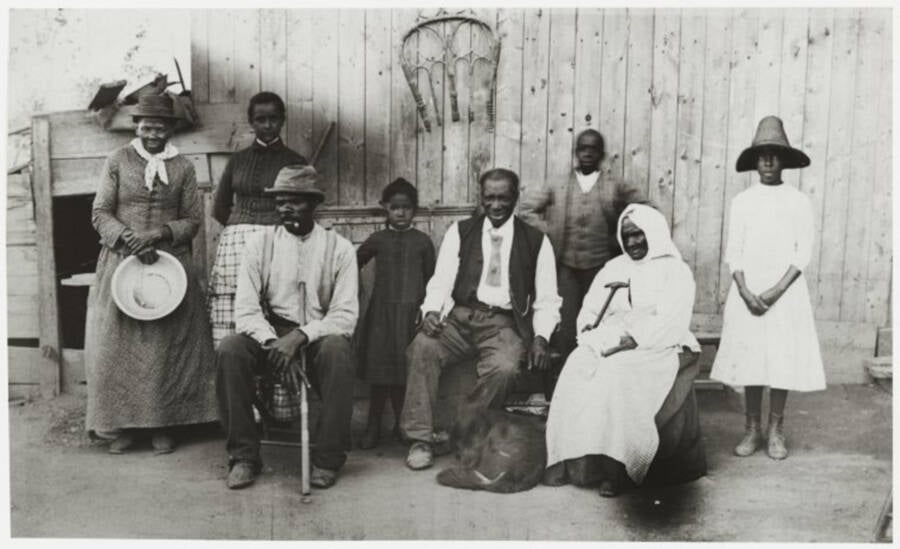

Wikimedia CommonsFrom left to right: Harriet Tubman, Gertie Davis (Tubman’s adopted daughter), Nelson Davis (Tubman’s second husband), Lee Chaney (Tubman’s neighbor’s child), “Pop” John Alexander (an elderly boarder in Tubman’s home), Walter Green (the neighbor’s child), Blind “Aunty” Sarah Parker (an elderly boarder), and Dora Stewart (the great-niece and granddaughter of Tubman’s brother Robert Ross, otherwise known as John Stewart).

A U.S. Marshall who refused to return a runaway slave, for instance, would be fined $1,000. This forced Underground Railroad security to tighten, and led the organization to create a secret code. It also changed the final destination from America’s North to Canada, to ensure permanent freedom.

These trips were usually scheduled for the nights in the spring or fall, when the days were shorter but the nights weren’t too cold. Tubman was armed with a small pistol during these missions, and routinely drugged young children to keep slave catchers from hearing their cries.

“I was conductor of the Underground Railroad for eight years, and I can say what most conductors can’t say – I never ran my train off the track and I never lost a passenger.”

Tubman intended to bring along her husband, John, on her third trip in September 1851, but found he had remarried and wanted to stay in Maryland. Returning North, she found more runaways than she expected waiting for her guidance in Garrett’s home, but soldiered on.

She led the passengers into Pennsylvania, to the safe house of Frederick Douglass. He sheltered them until enough funds accrued to continue on to Canada, where slavery had been abolished in 1834. Tubman got the 11 runaways to St. Catherine in Ontario, where she lived herself starting in 1851. In 1857, she managed to bring her elderly parents up to join her.

The following year, she met John Brown, the white abolitionist who shared Tubman’s passion against slavery. According to Larson, “Tubman thought Brown was the greatest white man who ever lived.” Brown shared a similar affection for her, as he once introduced her thusly: “I bring you one of the best and bravest persons on this continent — General Tubman as we call her.”

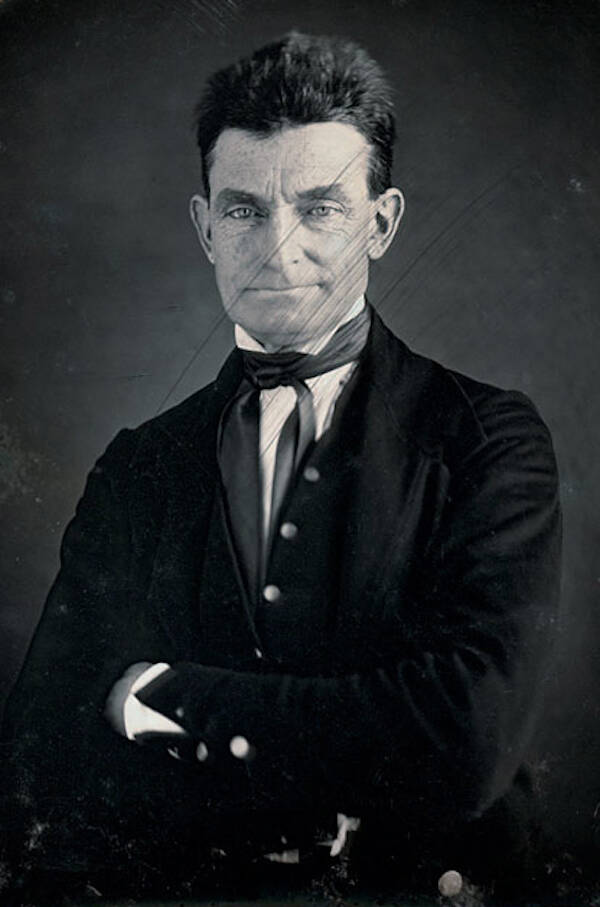

Wikimedia CommonsA portrait of John Brown by Augustus Washington from 1846, one year before he met Frederick Douglass.

But their friendship only lasted a year. In 1859, Brown led a raid on a federal arsenal in Harpers Ferry, Virginia, intending to spark a nationwide slave revolt. Tubman helped him recruit men for the raid, but illness prevented her from joining.

The raid failed, and Brown was summarily hanged for treason. Tubman’s illness was fortunate timing – for her and for the country, as her hard-boiled discipline, resourcefulness, and ingenuity served her well as a Union Army spy during the Civil War.

A Hidden Figure Of The Civil War

By the time the Civil War broke out in April 1861, Tubman had moved back to the United States — then-Senator William Seward, an admirer of hers, had given her a house on seven acres of land in Auburn, New York. Women were encouraged to enlist in the Union Army as cooks and nurses, which Tubman saw as an opportunity to join as a “contraband” nurse in a Hilton Head, South Carolina hospital.

“I grew up like a neglected weed — ignorant of liberty, having no experience of it. Now I’ve been free, I know what a dreadful condition slavery is….I think slavery is the next thing to hell.”

Contrabands were black Americans whom the Union Army previously helped escape from the South. They were typically malnourished or ill, due to the harsh conditions they’d been living in. Tubman nursed them back to health using herbal medicines, and even tried to find them jobs afterwards.

In 1863, Col. James Montgomery put Tubman to work as a scout. She gathered a group of spies who kept Montgomery up to date regarding slaves who might be interested in joining the Union Army.

Tubman also helped Montgomery plan the Combahee River Raid, unique among Civil War raids for its main goal of liberating slaves.

Wikimedia CommonsHarriet Tubman after the Civil War.

Many of these freed slaves subsequently joined the Union Army.

Still, because much of her work for the Union was secret, Tubman was denied a government pension for more than 30 years. In 1899, Congress finally passed a bill granting Tubman a pension of $20 per month for her service as a nurse.

Women’s Suffrage And Harriet Tubman’s Legacy

During the Civil War and in the decades after, Harriet Tubman lent her voice to the women’s suffrage movement, recognizing that a truly free society required not only the abolition of slavery and racism, but also of gender discrimination.

Library of CongressHarriet Tubman, pictured here in 1911, spent her last days at the her own Tubman Home for Aged and Indigent Negroes in Auburn, New York.

In 1896, when Tubman was already well into her 70s, she spoke at the first meeting of the National Association of Colored Women. The organization’s general goal was to improve the lives of African Americans, and it was also founded in response to the most prestigious and well-known women’s organizations, which were mostly white and mostly focused on white women’s issues.

But even though most white suffragists weren’t keen on focusing on issues specific to black women, Tubman did have one admirer in suffragist icon Susan B. Anthony.

“I bring you one of the best and bravest persons on this continent — General Tubman as we call her.”

“This most wonderful woman — Harriet Tubman — is still alive,” she wrote in an inscription on her copy of Tubman’s biography. “I saw her but the other day at the beautiful home of Eliza Wright Osborne….All of us were visiting at Mrs. Osbornes, a real love feast of the few that are left, and here came Harriet Tubman!”

Also in 1896, Tubman used the funds from her biography to buy 25 more acres of land in Auburn, New York. With help from a local black church, she opened the Tubman Home for Aged and Indigent Negroes in 1908. She soon moved into the facility herself, staying in a building called John Brown Hall until her death from pneumonia on March 10, 1913.

Harriet In Harriet

It’s impossible to sum up the astounding life of Harriet Tubman in two hours (or in 2,500 words, for that matter), but the 2019 film Harriet aims to do just that, charting the fearless abolitionist’s journey from slave to Underground Railroad conductor, as portrayed by British actress Cynthia Erivo.

The film’s tagline — “be free or die” — comes from an old legend about Tubman’s perilous journeys on the Railroad. The story goes that if any of her “passengers” wanted to give up and turn back, she’d pull her pistol on them and proclaim, “You’ll be free or die a slave!”

After learning about the astonishing life of Harriet Tubman beyond the Underground Railroad, delve into the life of Mary Bowser, another former slave who helped bring down the Confederacy. Then, read the little-known story of Ona Judge, the slave who escaped from George Washington.