Determined to end slavery at any cost, militant abolitionist John Brown led the failed 1859 uprising at Harpers Ferry, Virginia — and helped push the nation toward the Civil War.

Long before his failed raid on Harpers Ferry, John Brown occupied a place all his own in the abolition movement — and not just because he was white. After all, many white people in the United States opposed slavery on purely moral grounds.

What set John Brown apart from his contemporaries was that he’d had enough of trying to use peaceful discourse as a means to end slavery. He opted instead for violence — and was executed for it.

The Northerner began by collaborating with the Underground Railroad to found an armed militia, called the League of Gileadites, committed to preventing the capture of escaped slaves.

But his most notable effort, Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry, was also the one that halted his efforts altogether. His raid was ultimately unsuccessful but it inspired countless others to oppose slavery — violently, if necessary — and paved the way for the Civil War.

I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land can never be purged away but with blood. I had, as I now think, vainly flattered myself that without very much bloodshed, it might be done.

Brown’s methods are still hotly debated amongst historians and activists to this day. Was John Brown a militant terrorist with utter disregard for the law, or was he a righteous freedom fighter, opposing a violent practice with equally violent means?

John Brown’s Abolitionist Roots

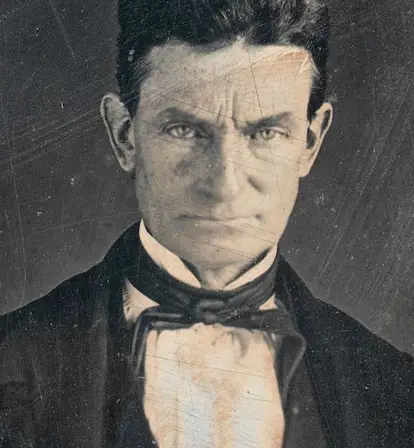

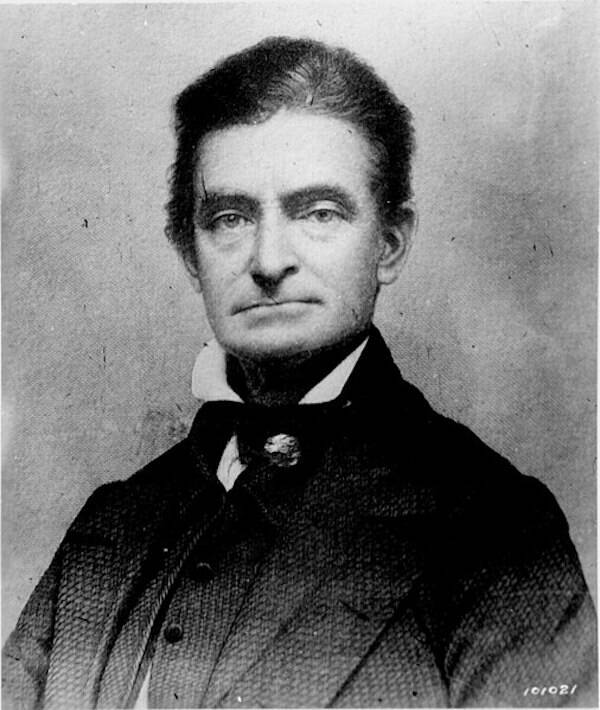

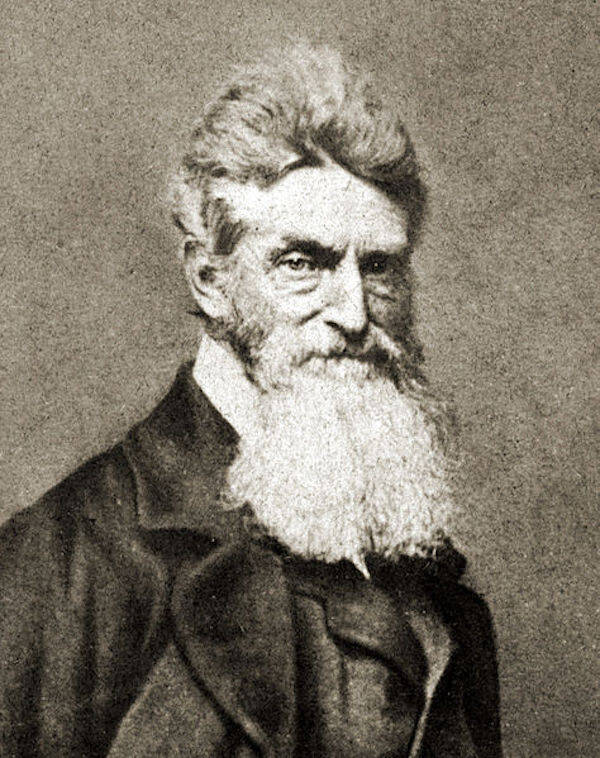

Wikimedia CommonsA portrait of John Brown by Augustus Washington from 1846, one year before he met Frederick Douglass.

John Brown was born on May 9, 1800, in Torrington, Connecticut to Calvinist parents Ruth Mills and Owen Brown. His father, who worked as a tanner, taught Brown that slavery was immoral from an early age and opened their home as a safe stop on the Underground Railroad.

Brown witnessed the barbarity of slavery when he was 12 years old and saw a Black child beaten in the streets while he was traveling through Michigan. That experience followed him for years and became a mental image he’d return to throughout the course of his life.

“Whereas slavery, throughout its entire existence in the United States, is none other than the most barbarous, unprovoked and unjustifiable war of one portion of its citizens against another portion, the only conditions of which are perpetual imprisonment and hopeless servitude, or absolute extermination, in utter disregard and violation of those eternal and self-evident truths set forth in our Declaration of Independence.” — John Brown, Provisional Constitution and Ordinances for the People of the United States, 1858.

According to The Smithsonian, the Brown family moved to Hudson in frontier Ohio when Brown was young. The Native American population was shrinking drastically during this time. There, the Browns established themselves as friends of the Indigenous people.

Brown and his father also continued to work together as “conductors” on the Underground Railroad, helping runaway slaves to safety. There was arguably no one more influential in Brown’s moral code regarding slavery than his father.

Establishing A Bold Reputation

Brown tried his hand at a variety of vocations ranging from farmer and tanner to surveyor and wool merchant. He married twice and fathered 20 children, one of whom was adopted and Black. Unfortunately, his first wife died, as did half of their children during infancy.

In his community, he demonstrated his anti-racist views by sharing meals with Black people and addressing them as “Mr.” and “Mrs.” He also vocally denounced segregated seating in church.

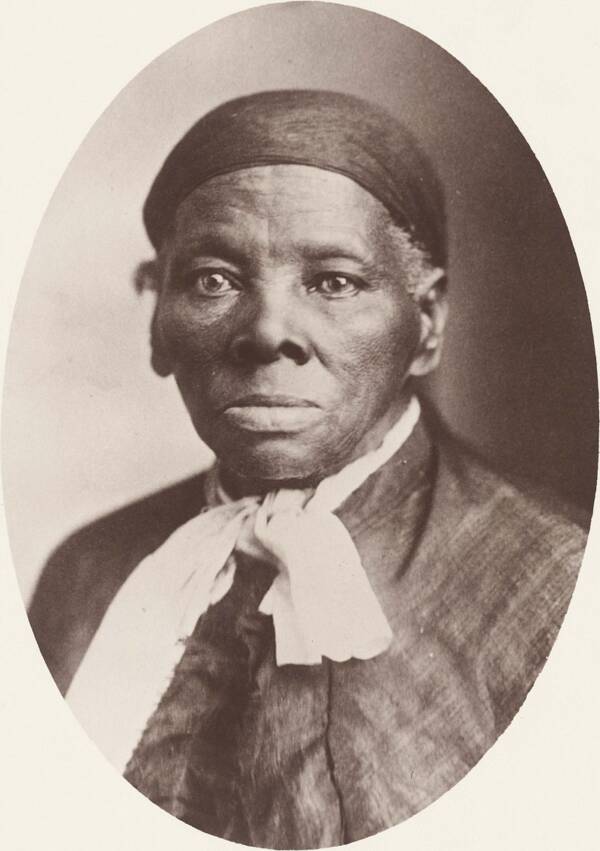

Wikimedia CommonsHarriet Tubman helped John Brown recruit men for his 1859 raid on Harpers Ferry but she didn’t involve herself further for fear that the Underground Railroad could be exposed should Brown’s plan fail.

Brown’s Calvinist upbringing had convinced him that fighting against slavery was his primary mission in life. He believed it was a sin so thoroughly that Frederick Douglass, who he met in 1847, said, “[John Brown was a man who] though a white gentleman, is in sympathy, a Black man, and as deeply interested in our cause, as though his own soul had been pierced with the iron of slavery.”

It was during this initial meeting with Douglass that Brown began to craft a serious plan to lead a war against slavery. A year later in 1848, Brown met abolitionist Gerrit Smith who urged him and his family to move to North Elba, New York with him.

There Smith had established a Black community across 50 acres of land which Brown saw as an opportunity to expand upon his anti-slavery project. He first established his own farm there and helped enslaved families with their agrarian work as a leader and “kind father to them.”

Wikimedia CommonsJohn Brown’s house in North Elba, New York. He taught local Black families how to farm and was eager to help them become independent and self-actualized.

Brown also drew up a plan he called the “Subterranean Pass-Way,” which would lead south from the Adirondack mountains through Allegheny and the Appalachian mountains. He envisioned it as an underground passage that would extend the Underground Railroad into the deep South.

The route was dotted with forts held by armed abolitionists and the idea was to raid plantations and free as many slaves from there as possible, which he hoped would cause the slave economy to plummet.

As Harvard historian John Stauffer put it, “The goal was to destroy the value of slave property.” He never carried out this plan, and it essentially became the blueprint for the raid on Harpers Ferry and made strategic sense — even if Brown ultimately failed.

However, according to National Park Service’s chief historian at Harpers Ferry, Dennis Frye, the plan “could have succeeded.”

“[Brown] knew that he couldn’t free four million people,” he said. “But he understood economics and how much money was invested in slaves. There would be a panic — property values would dive. The slave economy would collapse.”

In the next few years, however, Brown and his men would employ far more vicious means than these in their goal to defeat slavery.

John Brown Fights Against The Fugitive Slave Law Of 1850

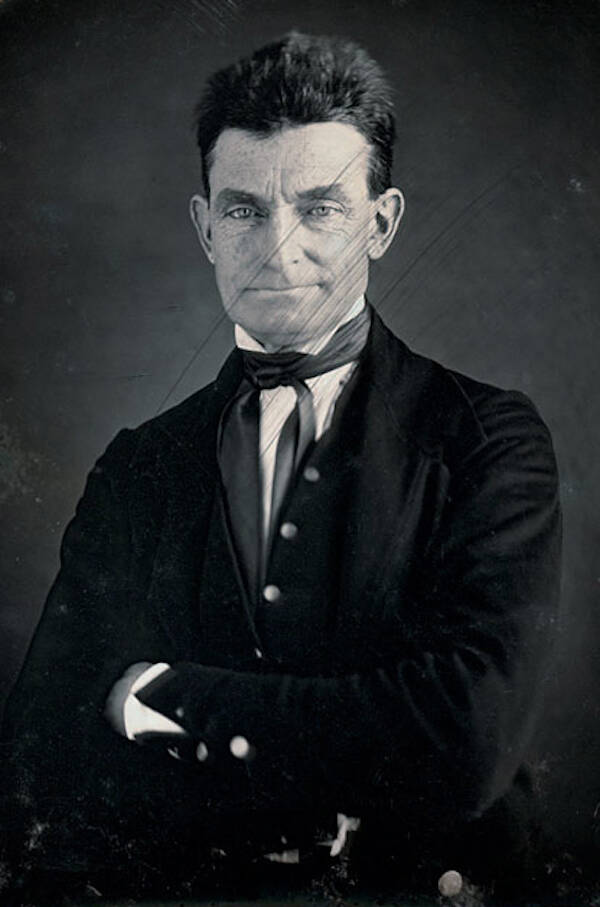

Wikimedia CommonsAn 1856 daguerreotype engraving of John Brown. That year he killed five pro-slavery men with sharpened, cut glass.

The Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 marked a turning point for Brown. The law established extreme punitive measures for anyone who helped runaway slaves, and Brown and other abolitionists saw no alternative to this criminality than violence.

In response, Brown formed a militia he called the League of Gileadites dedicated to helping and protecting escaped slaves.

In 1854, Congress permitted both Kansas and Nebraska to engage in slavery under something called “popular sovereignty.” In a letter to his father, Brown lamented these decisions on behalf of his government.

He wrote, “The meanest and most desperate of men, armed to the teeth with Revolvers, Bowie knives, Rifles & Cannon, while they are not only thoroughly organized, but under pay from Slaveholders,” flooded into Kansas.

Thousands of abolitionists — including Brown and five of his sons — packed their guns, left their homes, and headed to Kansas “to help defeat Satan and his legions.” They were headed to a battle.

As if Brown had not been motivated enough to take to violence, in May 1856, he learned that the most outspoken abolitionist in the Senate, Charles Sumner of Massachusetts, had been beaten on the Senate floor by a South Carolina congressman.

In response, Brown led his men to drag five pro-slavery men out of their cabins in Kansas’ Pottawatomie Creek. They hacked them to death with pieces of sharpened, cut glass. Even abolitionists were distraught, to which Brown merely replied, “God is my judge.”

Wikimedia CommonsWhen Brown’s son Frederick was shot and killed in Kansas in 1856, he was reminded how fragile his own life was.

Brown was a wanted man at this point, though nearly no one was put on trial for murder during the intense guerrilla warfare of this time. The violence only escalated. Pro-slavery “border ruffians” raided Free-Staters’ homes and abolitionists avenged themselves with arson campaigns, turning farms to ash.

Even Brown’s own son, Frederick, was shot to death by a pro-slavery man. This starkly reminded Brown of his own mortality.

“I only have a short time to live — only one death to die, and I will die fighting for this cause,” he told his son, Jason, in August 1856.

“Brown viewed slavery as a state of war against Blacks — a system of torture, rape, oppression and murder — and saw himself as a soldier in the army of the Lord against slavery. Kansas was Brown’s trial by fire, his initiation into violence, his preparation for real war. By 1859, when he raided Harpers Ferry, Brown was ready, in his own words, ‘to take the war into Africa’ — that is, into the South.” — University of New York historian David Reynolds, author of John Brown, Abolitionist: The Man Who Killed Slavery, Sparked The Civil War, and Seeded Civil Rights.

The Planning Stages Of John Brown’s Raid

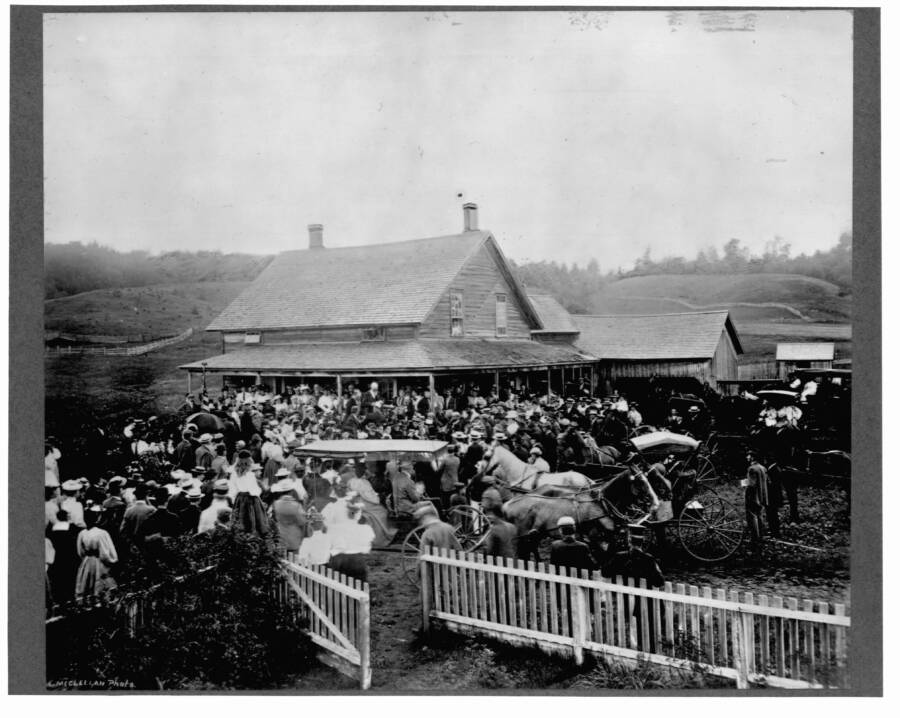

McClellan-Whittemann/Library of Congress/Corbis/VCG via Getty ImagesA mob surrounded John Brown’s house in Saranac Lake after he instigated the Harpers Ferry insurrection.

Brown left Kansas in 1858 to properly organize a Southern invasion he’d envisioned for the last 10 years. He planned to invade Virginia with a small militia, take the federal reserve stored at Harpers Ferry, and incite a slave uprising from the surrounding territories.

Perhaps he didn’t know it would, but John Brown’s raid also helped to incite the Civil War. Indeed, the raid would later be dubbed by some historians as “the dress rehearsal for the Civil War.”

Brown used funds from a group of rich abolitionists known as the “Secret Six” to buy hundreds of carbine rifles and thousands of pikes. He thought that once his men took Harpers Ferry, they could obtain a thousand additional rifles stored at its federal reserve.

The large federal armory was comprised of a musket factory, rifle works, an arsenal, numerous mills, and a major railroad junction just 61 miles northwest of Washington, D.C. It was, therefore, a prime location to incite a rebellion.

John Brown’s plans for the raid seemed to truly gel when he met Harriet Tubman who had already brought dozens of slaves to freedom through eight successful trips to Maryland’s Eastern Shore.

Brown respectfully called her “General Tubman,” while she considered him the greatest white man alive. Her sentiment was largely rooted in the fact he understood that abolition required tough choices.

He had previously led 12 fugitive slaves to safety in Canada, navigating treacherous landscapes of pro-slavery fighters and U.S. troops. This success assured him that it was possible to take Harpers Ferry.

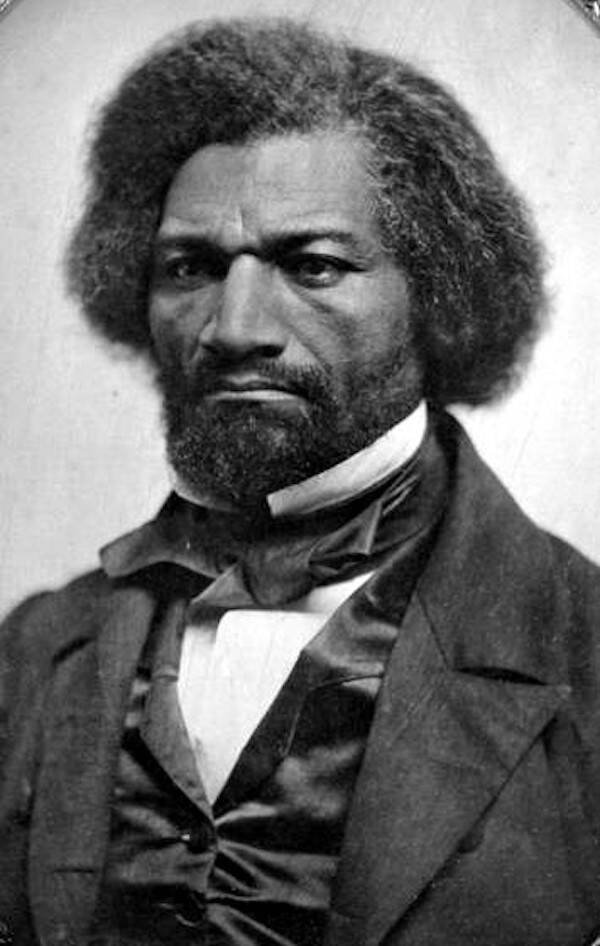

Wikimedia CommonsFrederick Douglass said of Brown that his “zeal in the cause of freedom was infinitely superior to mine. Mine was as the taper light; his was as the burning sun.”

Brown preemptively asked Frederick Douglass to agree to be president of a “Provisional Government” should he succeed in taking the Ferry. Brown also wanted Harriet Tubman to help him to recruit men for his army.

But in the end, Douglass wasn’t convinced Brown’s mission would succeed and he declined. Tubman did help to recruit followers but didn’t involve herself further as she feared John Brown’s raid could result in the exposure and destruction of the Underground Railroad if it failed.

Harpers Ferry was an industrialized town with a population of 3,000. More importantly, 18,000 slaves, which Brown called the “bees,” lived in its surrounding counties. Brown was confident he’d have their support when the time came.

“When I strike, the bees will swarm,” he told Douglass.

He was wrong.

The Harpers Ferry Raid Fails Disastrously

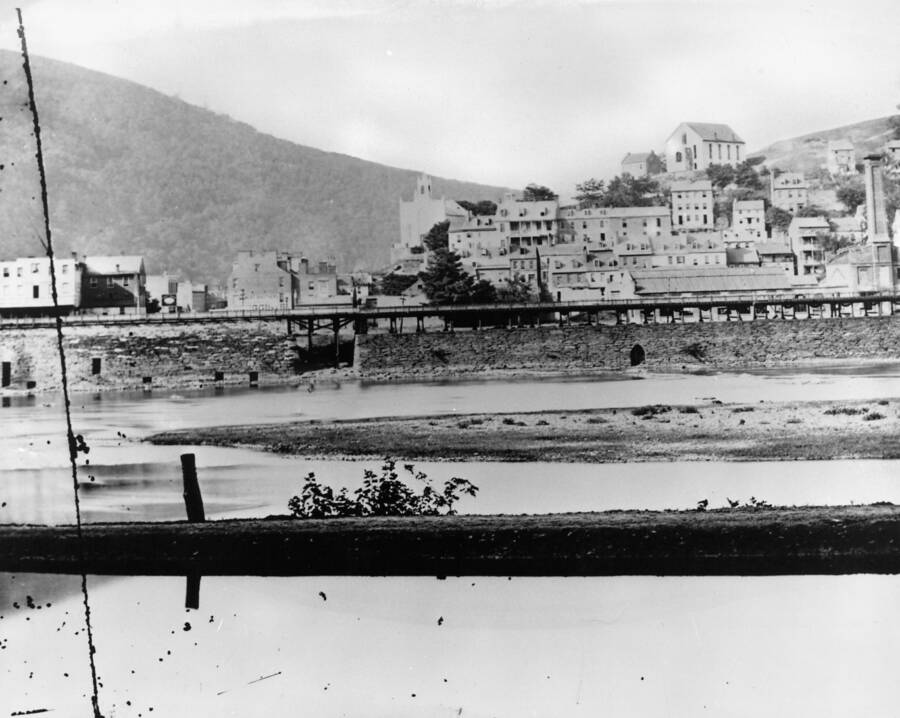

Time Life Pictures/National Park Service/Harpers Ferry National Historic Park/The LIFE Picture Collection via Getty ImagesA riverside view of Harpers Ferry where Brown and his band of abolitionists made their stand on Oct. 16, 1859.

On the night of October 16, 1859, Brown and 18 of his men descended upon Harpers Ferry.

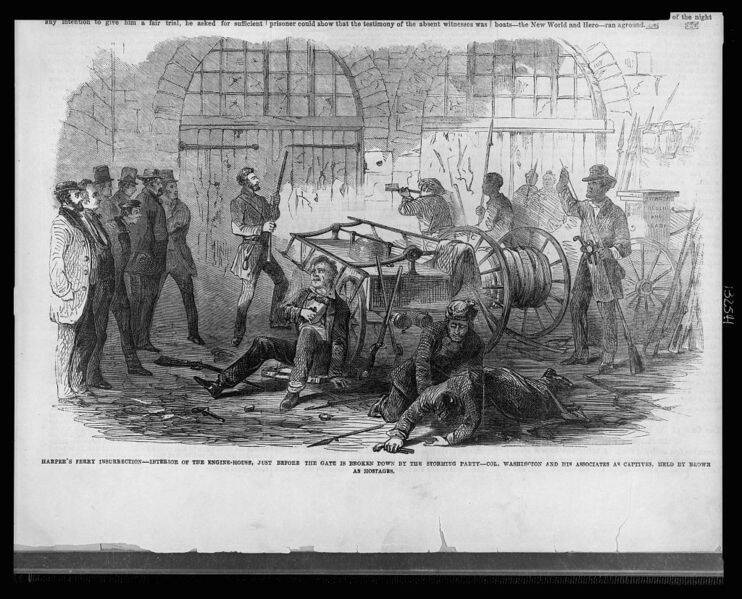

Brown ordered a group to take over the musket factory, rifle works, and arsenal. His men took hostages and a fire-engine house to use as their stronghold. According to Tony Horwitz’s Midnight Rising: John Brown and the Raid That Sparked the Civil War, Brown told one of the detainees there that:

“I came here from Kansas. This is a slave state. I want to free all the Negroes in this state. I have possession now of the United States armory, and if the citizens interfere with me, I must only burn the town and have blood.”

The men then seized the railroad station and cut the telegraph lines to prevent any distress calls to outside forces. The first casualty fell at the station, however, when a free Black man named Hayward Shepherd challenged Brown’s army and was shot to death.

Brown dispatched a contingent to snatch up local slaveowners — including Colonel Lewis Washington, a great-grandnephew of America’s first president.

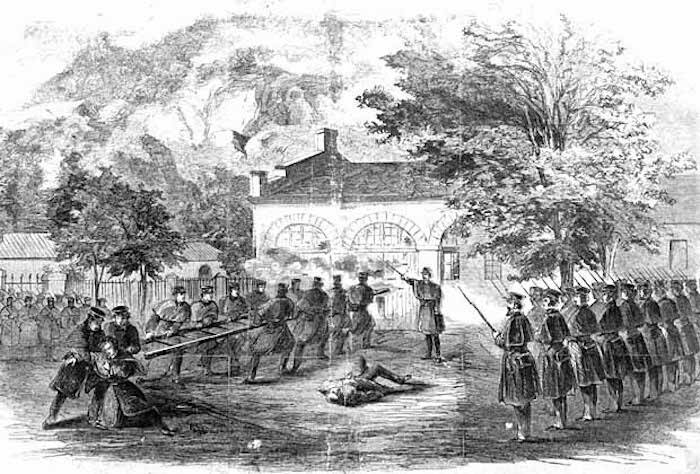

Wikimedia CommonsA Harper’s WeeklyMarines rushed the firestation where John Brown and his men camped during the Harpers Ferry raid. Only a few survived the seige and two-day battle that followed.

At this point, Harpers Ferry had been commandeered by up to 200 white “insurrectionists” and “600 runaway negroes.” But those “bees” Brown was so confident would swarm didn’t, and as dawn arrived, regional white militias neared.

The Jefferson Guards were first to arrive and they seized the railway bridge and thus Brown’s only escape route. Armed militias from Maryland, Virginia, and elsewhere arrived in Harpers Ferry soon thereafter and surrounded Brown and his men who hid in the fire-engine house.

When Brown sent his son Watson out to surrender with a white flag, the 24-year-old was shot in the street, forcing him to crawl back seriously wounded.

When the militias stormed the firehouse, some of Brown’s men jumped into the Shenandoah or Potomac rivers and were shot dead. Others surrendered and lived.

The violent day turned to a desperate night. The trapped army hadn’t eaten in 24 hours and only four were unwounded. Brown’s 20-year-old son Oliver lay dead. His older son Watson moaned in great pain and Brown told him to die “as becomes a man.” Around 1,000 men surrounded the hopeless group.

Even President James Buchanan got involved in ending the rebellion. Lieutenant Colonel Robert E. Lee, a slaveowner himself, led an army to handle Brown’s insurrection.

Dressed in plainclothes, Lee arrived at midnight and amassed 90 Marines behind a nearby warehouse to plan his approach. In the dead of night, one of his aides walked up to Brown’s stronghold carrying a white flag. Brown opened the door and asked if he and his men could return to Maryland to free the remaining hostages. The plea was rejected.

Wikimedia CommonsJohn Brown (center-left) and his men inside the Harpers Ferry firehouse before the militias and Marines defeated them.

The aid signaled for Lee’s men to attack, at which point Brown could’ve shot him “as easily as I could kill a mosquito,” he later recalled. He decided not to, though, and Lee’s men raided the building from all available paths of entry.

Brown was nearly killed with a saber, but it hit his belt buckle and merely hurt him. He was then beat over the head until unconscious.

“If the blade had struck a quarter-inch to the left or right, up or down, Brown would have been a corpse, and there would have been no story for him to tell, and there would have been no martyr,” said Frye.

Nineteen men took Harpers Ferry the day before. Five of those were now prisoners and 10 died in the violence. Four townsfolk died and over a dozen militiamen wounded. Only two of Brown’s men successfully escaped across the Potomac during the Harpers Ferry raid.

The Trial And Execution Of John Brown

Wikimedia CommonsThe country was already thoroughly divided by slavery, but John Brown’s insurrection and subsequent execution only fanned the flames.

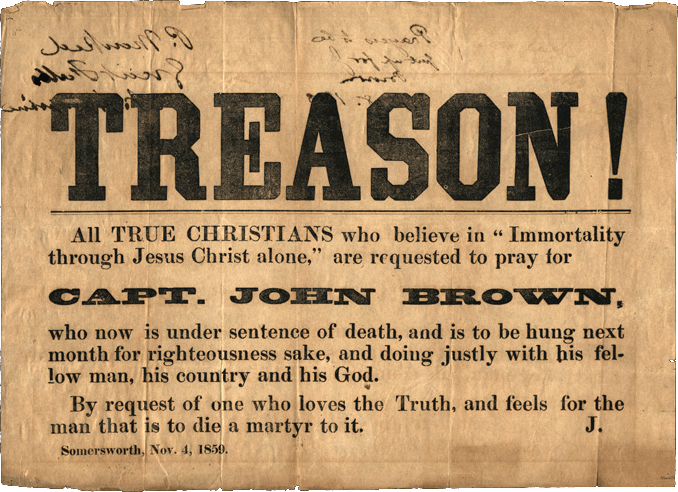

Every man captured at the raid on Harpers Ferry was charged with treason, first-degree murder, and “conspiring with Negroes to produce insurrection.” The death penalty loomed over them all following a trial held in Charles Town, Virginia on Oct. 26, 1859.

Brown was sentenced to death on Nov. 2 and waited a month to meet his end.

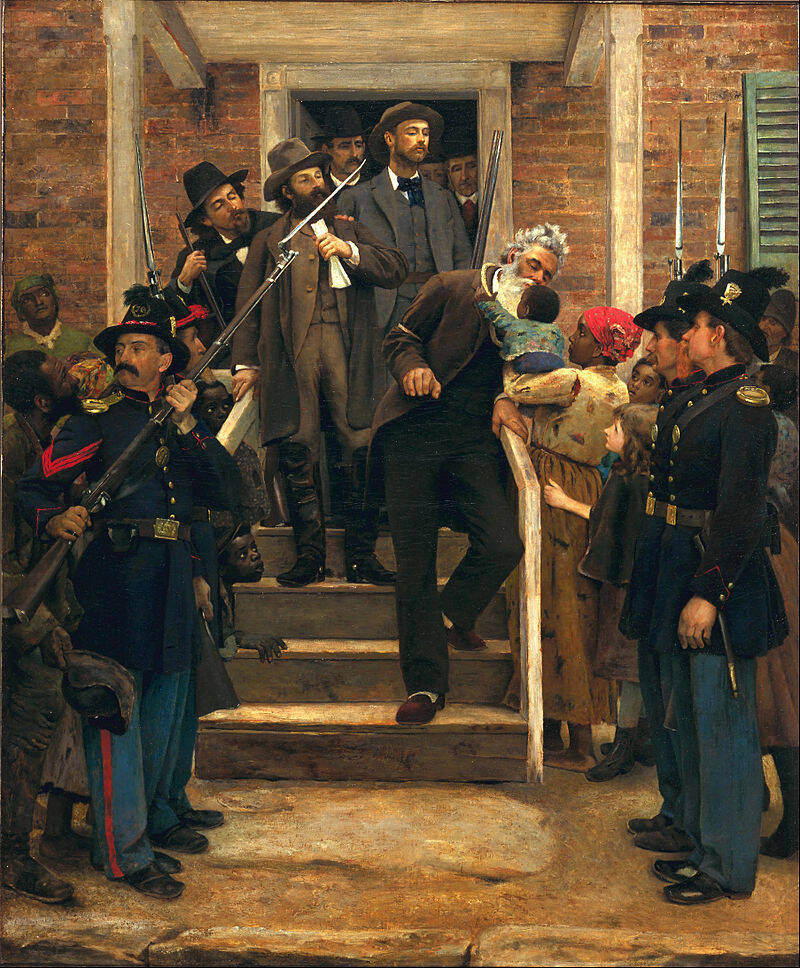

Escorted out of jail on Dec. 2, Brown was flanked by six companies of infantry. He sat on his coffin as his wagon wheeled to a scaffold.

“In the first place, I deny everything but what I have all along admitted, the design on my part to free the slaves…I never did intend murder, or treason, or the destruction of property, or to excite or incite slaves to rebellion, or to make insurrection.” — John Brown, from his speech to the court, 1859.

A sack was placed on his head. Brown told the executioner:

“Don’t keep me waiting longer than necessary. Be quick.”

Present at Brown’s execution were Robert E. Lee, Thomas J. Jackson, who would become “Stonewall” Jackson at the Battle of Bull Run two years later, and John Wilkes Booth, the man who would assassinate Abraham Lincoln.

Wikimedia CommonsThe Last Moments of John Brown by Thomas Hovenden in 1888.

But Brown’s death only emboldened both the pro- and anti-slavery factions, contributing to further polarization. Henry David Thoreau referred to Brown as “an angel of light” and likened him to Jesus in a speech at Concord the following day. At the same time, southerners feared further insurrection.

“In effect, 18 months before Fort Sumter, the South was already declaring war against the North,” said Frye. “Brown gave them the unifying momentum they needed, a common cause based on preserving the chains of slavery.”

Thus, John Brown became both a hero of the abolitionist movement and a treasonous man of violence to those hoping to preserve slavery. He arguably also hastened the Civil War. John Brown’s story is thus the story of America in his time: Ideologically torn and defined by both moral clarity and an abundance of violence.

After learning about the militant abolitionist work of John Brown and his raid on Harpers Ferry, read about North Carolina slave Henry Brown who mailed himself to freedom. Then, learn about Lewis Powell, John Wilkes Booth’s coconspirator who failed spectacularly.